Newly consecrated Bishop Irénée Rochon shares his reminiscences about the ROCOR and his hopes for the future of Orthodoxy in Northern America. Hewas tonsured and ordained within the Russian Church Abroad.

Could you please tell us about your background?

Born in 1948 in a large French Canadian family, the youngest of my generation, I was brought up in the Roman Catholic school of the time. My family owned a hotel in Rawdon, where there was a good size summer Russian community. It is there that in 1960 or 61, I met a Russian family which was to become my introduction to Orthodoxy. In 1961, I accompanied these friends to St. Seraphim’s church for the first time. After this experience, I could never tear myself away from the Russian church.

I was then a practicing Roman Catholic, and so I found out about Byzantine rite churches in Montreal, and began attending services there, hoping to satisfy this longing for the Church. I began learning Russian and Church Slavonic there, signing in the choir and serving in the altar.

I finished High School in 1966 and it is then that I decided to join the Orthodox Church.In December I turned 18 and in January 1967 was received into Holy Orthodoxy at the Brotherhood of Saint Job of Pochaev chapel by Archbishop Vitaly Oustinov.

What was the cultural atmosphere in Quebec at the time you became an Orthodox?

These were times of change in the Province of Quebec. After 200 years of British domination, the people were awakening and realizing that they were a nation, a nation with talent, and dreams. Expo 67 in Montreal was one of the realization of the times. Along with this awakening which was called the Quiet Revolution, came a desertion of the churches by the French Canadians. My desire to be part of the Orthodox Church happened many years before and thus I was not influenced by this movement out of the Roman Catholic Church. I watched it happen from the outside. I was very active in the parish life at Saint Nicholas Cathedral in Montreal and in the Pokrov parish in Ottawa, where I was doing my college degree.

How did you happen to join the ROCOR?

There was never a choice as such, Saint Nicholas Cathedral was much closer to my home than the Metropolia church of Saints Peter and Paul. The residence of Vladika Vitaly and the Brotherhood was a block away from my home. From 1967 to 1970, I was active in the McGill University OCF, which was spiritually nourished by Metropolia clergy. After University, I wanted to go to seminary, but my belonging to ROCOR made going to Jordanville easier. I accompanied a friend who was going there to study and I liked it and decided to return which I did in the Fall 1971.

I understand that when you began your monastic life in Jordanville there was a trend to Russify non-Russian novices so that they could participate in a vibrant Orthodox tradition. Did you feel this pressure on yourself? How would you characterize your experience at Jordanville?

Yes, this trend definitely existed. This theory found followers among the Leaders of the Seminary. This did cause a lot of difficulty as I was not a recent convert at the time, I already had a knowledge of Russian and Church Slavonic and I was very happy being French Canadian. An added difficulty at the time was the increasing number of American converts, and I often found myself in between the Americans and the Russians. I always felt this was not necessary.

After I became a novice in 1973, I was asked to help care for the ailing Archbishop Averky. I never felt this from him at any time. I served Vladika Averky until his falling asleep in 1976. My spiritual Father was Archimandrite Kiprian and with him we always spoke French, and so I never felt this pressure from him either. My Russian improved as time went on and eventually was able to get to converse and to know such great people as Archimandrites Anthony, Serge, Vladimir, and so many more of the holy men who made Holy Trinity Monastery the spiritual bastion that it was. After Archbishop Averky’s death, the new Abbot, Bishop Laurus, gave me his blessing to go to the Western European Archdiocese, so as to be in contact with French speaking Orthodox and their parishes. It is then that I was ordained hierodeacon and hieromonk by Archbishop Antony of Geneva. I served as supply priest for the Archdiocese in French and Russian parishes.

In what ways were the mindsets of American and European parishes of the ROCOR distinct from each other in the 1980s?

From one continent to another, things were much different. In Europe, concelebration with other Churches was unofficially accepted except for the Moscow Patriarchate. Whenever, we would travel abroad, Vladika Antony would tell us to commemorate the local Orthodox hierarchy.

In America and Canada, things were very much different, because of the influence of certain extreme groups who had found refuge in ROCOR. There was also a ‘’home grown’’ version of this within ROCOR, which was eventually to lead to the unfortunate schisms that we know today.

What was the situation within the Canadian diocese of the ROCOR when you started your French speaking mission in Montreal?

After my return to Montreal, in 1982, I was confronted to this exclusive Orthodoxy which made functioning and building a viable mission quite difficult. There was only one official way to behave towards anyone who was not of ‘’our’’ opinion and this was very much different from what I had been used to in Vladika Antony’s Archdiocese. In Canada, you had to be of one mind with the official way of thought which came from above. All were shaped by one man in his way of thinking, and no one was permitted to disagree with it. This in the long run became the basis of the Mansonville schism. Fear, threats, blind acceptance and exclusivity of the leaders’ point of view were every day’s lot. There was no other ROCOR diocese in Canada to move to. One country, one diocese. The only way to get away from this was asking to be received into the Canadian Archdiocese of the OCA.

Now you are a bishop. What is your vision of the canonical situation in Northern America?

I see jurisdictions as being part of today’s world, but we have to realize that the word jurisdiction is not synonymous of ‘’one and only church’’. In Europe, Archbishop Antony often spoke of common flock shared by Paris Exarchate, Western European Archdiocese and to a certain extent other national churches in this territory. It will be difficult to change the exclusive mentality, which would have jurisdictions own the people. I have seen this here in Canada in all national dioceses. What we all must have in mind is that we must work to help all Orthodox Christians, whatever their national heritage. That is why I serve in French, English, Slavonic, Greek. If it will help save souls, I will learn as many languages as necessary.

We have to start praying together. We have to pray for each other. It is essential that we respect each other. If we cannot witness together to the Truth that we profess, then our witness will not carry very far.

If we are to serve only a selected few, and ignore all the others who are starving for this Truth, then we are far from what the Church is about. Canonical reality in North America is very complex. We have to live with what our Fathers have handed down to us, but it must not be a stumbling block in our attempts to sanctify this world.

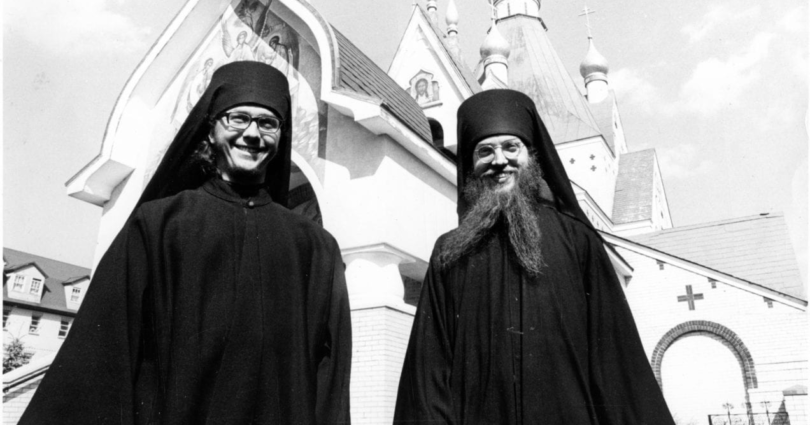

The First-hierarch of the OCA Metropolitan Tikhon with Archbishop Irénée of Ottawa. 2014. Photo: oca.org

What are the steps that can be undertaken that might bring us closer to a resolution of the canonical crisis in America?

Love, respect of each other, patience with each other’s weaknesses, and being assured that God knows what He is doing. Let us work with Him, not against each other. Things are far from being what they were 10 years ago, and I am sure that God will continue to guide His Church along the path He has chosen in His great Providence. We have to be careful not to go against His will.

Thank you Vladyka, for taking the time to answer our questions. Eis polla eti Despota!

Conducted by Deacon Andrei Psarev

Dear Fr. Andrei:

Looking at this photo again, I believe my memory may have failed me, and that the monk on the right in the photo of Archbishop Irénée on the day of his tonsure may have been named Christopher, rather than Nikifor. I only met him once, nearly 45 years ago, when I visited Jordanville briefly during my time in the Army. Vl. Irénée will remember his name, I’m sure.

Hello all,

His name in Orthodox baptism was Christopher (although I cannot remember what his birth name was, it was something funny like Rodney), he was tonsured into the little schema with the name of Nikifor. He lived in the monastery until he moved to the Synod in NYC where he served until he left when Archbishop Vitaly arrived following the death of Metropolitan Philaret. If anyone know where he is please send me a contact note at fabaomarcao@hotmail.com.

Mark Midensky

They are the same person: Christopher is his baptismal name, Nikifor his name in the little schema.