More than a year has now passed since Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Vladimir Maksimov, and other writers left the USSR to become latest Russian émigrés. Only now has it become possible even to begin discussing the status and aspirations of this new wave of Russian refugees with a modicum of objectivity. Many “public leaflets” (as Metropolitan Philaret of Moscow used to characterize certain newspapers of his time) have launched a veritable barrage of abuse at Solzhenitsyn, without the least attempt to keep a rein of their words and expressions. Such a rush to judgment testifies to the partisanship of the authors. There is a Russian fable about a silly dog that yaps at an elephant in an attempt to demonstrate its courage. It hopes that the bystanders will be so impressed that they will say, “What a dog! It certainly must be strong to bark at an elephant.” And that is just what can be said about the unworthy press attacks on Solzhenitsyn. Solzhenitsyn is indeed a giant and no one will succeed in reducing his stature. His enormous talent will always sweep him up above and above the daily turmoil of life.

Even wave of Russian emigration – past, present, and future – possesses its own unique store of experience and its own view of the world derived from this experience. This world view must be respected, it must be taken into account, and it must be carefully examined for the greater benefit of the entire Russian diaspora, and perhaps of the entire world.

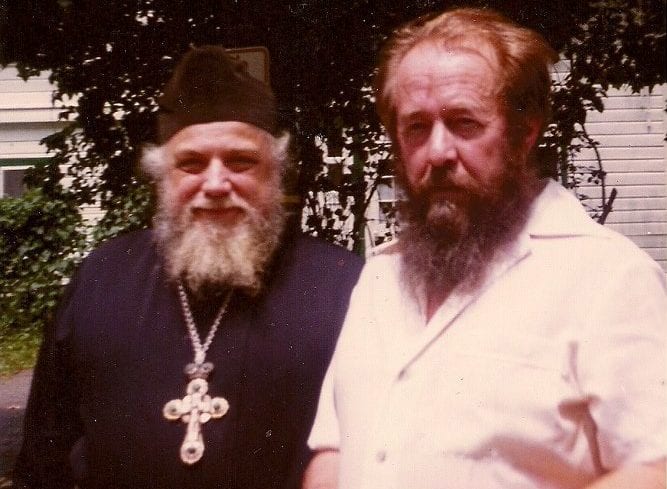

One must understand Solzhenitsyn, but he is a man of such a caliber that one must not hasten with predictions, conclusions, or final evaluations. Without any question he is an enormously important event in the life of Russia. We are not so bold to claim to be making a close study of this major figure on the pages of our Church Messenger [ Церковный вестник ], but we would like to lay at least the beginning of a reliable and claim introduction to such an analysis.

We can immediately distinguish three aspects of Solzhenitsyn: the literary artist, the thinker, and the political figure. In the linguistic medium of his works, Solzhenitsyn boldly seeks new directions for the Russian language, to use a fashionable phrase, he is seeking a new dimension. Since language is an inseparable part of the national spirit, we can only rejoice at this attempt, which demonstrates to us that the spirit of the Russian people is alive and wants to remain living. Dead tongues are not only those that are no longer used for daily communication, Such as ancient Hebrew, ancient Greek, or Latin. Nearly all the old nations of Europe are in real danger of finding themselves with dead languages. The artificial role assumed by the French Academy in bestowing French citizenship upon some words but not others is in essence terribly detrimental to the vitality of the French language. The English language draws its life mainly in the United States, in Canada, and in Australia. The world grows older, and so do the various people and their languages. Their words have become polished to jewel-like brilliance, they have been used to express every conceivable and inconceivable meaning, and they are gradually acquiring finished, final meanings; they are turning into petrified forms fit only for encyclopedic dictionaries – and that is already the threshold of death. But the death of the word occurs when man loses God from his heart, loses the concept of His infinitude, His boundlessness, and thus loses his ability to express the inexpressible in words.

Man was created a being in the image and likeness of God. He stands on the dividing line between the visible and the invisible. This extraordinary vantage point accords man with God’s gift of endowing his words with the power to extend every meaning, to engender new vistas and even entire worlds in the minds and hearts of other men. Such words from this kind of man are like stones cast onto the calm surface of a quiet lake. But he who stands only on the earth and does not believe in God – an atheist – can speak only of what his physical eyes and ears have seen and heard. His words are like the blows of a sledgehammer upon a coffin-lid: a dull and harsh sound and nothing more – no echo, no response. This death-bearing spirit pervades almost the whole of world literature, headed by Soviet (and by this we mean atheistic) literature. For we are living at a time of great universal apostasy, a renunciation of Christ the Lifegiver, under a multitude of guises, be it open and brazen atheism, blasphemous sectarianism, or deceptive ecumenism. Solzhenitsyn has perceived the tentacles of this literary octopus of death and he is making gigantic exertions to break free – to life. It is quite immaterial whether he does this consciously or intuitively – his great service to Russian and world literature is beyond dispute. His efforts to broaden the range of lexical and syntactical possibilities in Russian promises greater freedom from the dictates of narrow specialists and thereby injects new life into the language. But every writer has his share of disciples or mere imitators; Solzhenitsyns followers might devote themselves to polluting the Russian language with the gutter vocabulary of criminal riff-raff. A Latin proverb is appropriate here: “Quad licit Jovi, non licit bovi” (what is appropriate to Jove, is not a appropriate for cattle). In this case the standard, which will help us to judge, the eternal example of unfading beauty, simplicity, and profundity is the language of Pushkin.

But Solzhenitsyn’s bold attempt to enrich the Russian language is only a reflection of his spiritual make-up. Wise is the man who acknowledges his mistakes; great is only he who repents of them. Solzhenitsyn has passed this double trial of admitting his errors and of repenting for them in his readiness to lay down his life for his new Christian convictions. It is precisely such a repentant conversion that is at the core of all his works. As soon as he had recognized his errors, he pushed away with the entire strength of his soul – a soul that was capable of repenting – from the murky depths of the Communist hell and rose to take a deep breath of fresh air in God’ s world.

But the road of repentance is a process of slow spiritual purification, of gradual transformation. Solzhenitsyn has only begun this path and as a result the grace of God and the old man – with all his passions – are equally, operative in him. While his talent carries him onward at full sail, the process of purification cannot keep up. This discrepancy in the movements of his soul gives rise to all his errors. When Solzhenitsyn writes about ordinary sinful human beings, he does so with the full brilliance of his talent, because sinful men are being described by an equally sinful – but highly talented – writer, The Cancer Ward, the two volumes of the Gulag Archipelago, and the First Circle are the fruits of this talented Solzhenitsyn. But in One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich the reader can feel the oppressively restricted limits of the psychology of fallen nature. One expects more from Solzhenitsyn, one wishes for at least a small glimpse of higher spheres in the midst of this detailed, minute by minute catalogue of human torments. Matrena (in the short story Matrena’s Home) is a distinct failure. Solzhenitsyn did not understand her and as a result her depiction as a fool-for-Christ’s-sake is unsatisfactory, implausible, and incomplete. This is because Solzhenitsyn does not yet have an organ for perceiving holiness, the truth of Christ’s Church. In August 1914 the literary mastery and the psychological grasp are superb, but the aim of the book has not been achieved. Solzhenitsyn cherished plans to analyze the causes of the collapse of the Russian Empire remains a dream. In order to write history one must either possess great historical objectivity toward all past events, a quality the writer lacks; or else be maximally passionless, something A.I Solzhenitsyn has not yet achieved. The great and talented Writer in him presses ever forward, but a work of this type requires insight, it requires a pure heart, in order to soar like an eagle above the activities of the earth. In this respect we can apply to Solzhenitsyn the words that the famous Starets of Optina, the pious Makary, had said some 120 years ago about the great Russian writer Nikolai Gogol:

“We can see a man who has turned to God with heart-felt ardour. But that is not enough for religion. In order that it should be a true beacon for the man himself and that it should emit genuine light through him for his fellow men, religion needs certainty. This certainty consists in a clear grasp of the truth: the ability to distinguish truth from all that is false and from all that only appears to be true. The Savior Himself said to us: ‘The truth shall make you free’ (John 8:32). Elsewhere in the Scriptures it is written, ‘Thy word is truth’ (John l7: l7). Thus he who seeks certainty must immerse himself in the Gospels and direct his thoughts and feeling according to the teaching of our Lord. Then he will be able to instill in himself’ correct and good thoughts and feelings. Then man enters the realm of purity, as the Lord said after the last Supper to His disciples who had already; been enlightened by the teaching of the truth: ‘Now l have spoken unto you’ (John l5: 3). But purity alone is insufficient for man: he needs life and inspiration. Similarly, in order to lantern to give forth light it is not enough to clean the glass – the candle inside must be lighted too. The Lord did this with His disciples. Having purified them with the truth, He gave them life by the Holy Spirit, and they began to give forth light for mankind. Before they received the Holy Spirit, they were unable to teach men even though they were pure. This sequence must occur with every Christian, and in a very; real sense, not in name only; first the enlightenment by truth, then the illumination by the Spirit. It is true that man has an inborn, more or less developed inspiration, which arises from the stirrings of emotion. Truth rejects such inspiration as impure and kills it, so that the Spirit can resurrect it in a new state. But should man be guided by his own inspiration prior to being cleansed by the truth, than he will not emit pure light for himself and for others. Instead, it will be an impure, deceptive light, because his heart does not hold pure goodness, but good more or less commingled with evil. Let everyone examine himself and test my words by the experience of the heart: he will find my words accurate and just, taken from nature itself .

When Gogol’s book is viewed on this basis, one can say that the author emits both light and darkness. His religious concepts are not distinct, they move in the direction of all that is heart-felt, vague, instinctive, and characteristic of the psyche, not of the spirit. Gogol is a writer, and in the writer ‘out of the abundance of the heart the mouth speaketh’ (Matthew l2:34). This is to say that a literary work is necessarily a confession of its author, and one that he generally does not understand himself. It can only be a Christian who has been drawn by the Gospels into the abstract realm of thought and feeling and who has distinguished light from darkness within this realm. From this point of view Gogol’s book cannot be accepted as a pure word of truth. There is a commingling here. It is desirable that this man who exhibits selflessness, should find a mooring in the haven of truth, where all that is good has its beginning. For this reason I can recommend the following to all my friends: in matters of religion, they should study only the works of the Fathers who, like the apostles, had achieved both purification and enlightenment, and who wrote their books only after they had achieved this. Their books radiate the pure truth and transmit to their readers the inspiration of the Holy Spirit. Outside this path, which at the beginning is narrow and a arduous for the mind and the heart, there is only darkness, wild torrents, and precipices. Amen.”

The great starets has here said everything about Solzhenitsyn as well; we are not so bold as to add anything further to the characterization of Solzhenitsyn the thinker and the man of ideas.

There remains Solzhenitsyn the political figure. In our deceit-filled preapocalyptic times every civil regime, with the support of one party or another, attempts to gain control over the whole man. In the USSR every religious believer is considered an undesirable citizen, and anyone who shares his thoughts about the faith with others, even to the smallest degree, becomes an “enemy of the people”. The Sacred Scriptures are considered anti-governmental propaganda in the Soviet Union. On the basis of such reasoning, all believers are accused of antrgovernmental propaganda and illegal political activity. The Church is not involved in political activity it is the civil authorities that are intervening in the religious life of its citizens. The regime thereby tramples on the most sacred and basic, the most personal – and until now inviolate – freedom to think and to believe as one sees fit and to live by this thought this faith. Solzhenitsyn is not a political thinker at heart, and it was not by his choosing that he assumed a political role. His thoughts about the well being of his country follow naturally from his sincere conversion from communism to a Christian way of thinking. Having realized the absurdity and utopianism of communist doctrine, the unnatural essence of a teaching that can only be realized by force and violence, Solzhenitsyn could not but express his thoughts about the well being of his country in political, administrative, and even economic terms. But Solzhenitsyn nevertheless remains a literary artist and a thinker above all.

Rather than assailing Solzhenitsyn we must pray for him, so that the Lord should enlighten him even more. ln the face of Russia and of the entire world we Russians – joyfully thank the Lord that Solzhenitsyn is one of us.

Translated by Alexis Klimoff from Church Messenger [Tserkovnyi Vestnik]: Monthly Magazine of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia in Canada, 5-6 (May-June 1975)

This is a dated and very uneven, but interesting article. Archbp. Vitaly is completely wrong concerning `Matrena`s Home` and quite unhelpful in drawing an analogy between Solzhenitsyn and Gogol, but he makes valuable comments even in these contexts. I was struck by how the enthusiastic beginning and very positive overall evaluation at the end clashed with the criticism of the mid-section. As one who knew Vladyka Vitaly, I think it likely that he wrote his piece `in one breath` and did not bother to re-read. My translation suffered greatly in this transfer to pdf: words are missing

Ссылка на русский оригинал в pdf не работает.

Исправлено. Спасибо!

page not found

Русская статья не открывается.

Спасибо. Исправлено. См. ссылку вверху публикации.