Part IV, Chapter 1.9

The Dioceses of Australia & New Zealand

The Orthodox Russians in Australia all belong to the Church Abroad. The Moscow Patriarchate does not maintain parishes of its own in Australia. Their attempt to establish parishes there failed in 1968. In that year, small groups of faithful split from the Church Abroad over the question of church property. This dispute involved the registration of the Russian church property, which was valued at $200,000, and which had been administered by elected parish representatives until 1968. When, at this time, the parishes were supposed to register as the owners, various groups of the faithful, who wanted to maintain the status quo, protested against this. In a few communities, splits resulted. Among these were also two clergymen of the Sts. Peter & Paul Cathedral in Sydney, of whom one joined the Polish Orthodox Church and the other joined the North American Metropolia (though this did not result in the Metropolia making inroads amongst the Russians). The Patriarchal Church probably hoped at this point that there would be further schisms. In any event, Archbishop Leonid of Kharkov, accompanied by several clergymen, visited Australia at the invitation of the Soviet-Australian Friendship Society, though they met with practically no Russian émigrés. [1] Prav. Rus’ (1968) 22, p. 12. Also, the great majority of schismatics rejoined the Church Abroad in 1977. The schismatics from the Sts. Peter & Paul Cathedral held a vote; 87 people against 14 voted to place the church property under the Diocese of Australia & New Zealand. Additionally, it was decided that the “parish by-laws, as accepted by the Synod of Bishops in 1951, would form the legal basis for the Russian parishes.” [2] Ibid., (1972) 9, pp. 6-7; (177) 5, pp. 11-12.

Thus, peace in the Church in Australia was restored. In addition to the faithful of the Church Abroad, there are also groups of faithful in Australia who historically belong to the Church Abroad. The Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church in Exile cares for some 2,000 faithful there, who are organized into their own diocese under the rule of Metropolitan Mstislav. Fourteen parishes with about as many priests belong to the diocese. [3] Jahrbuch der Orthodoxie (1976/77) p. 188. The Ukrainian Greek Orthodox Church in Canada also has 15 communities and eight priests there. The number of faithful is unknown. [4] Ibid. (1972) 9, pp. 11-12. The Belorussian Autocephalous Orthodox Church is the third group represented in Australia. Since the death of their First Hierarch, Archbishop Sergius (Okhotenko), in 1971, the parish life of this group seems to have suffered a setback. Little is known about the number of parishes and faithful.

The first Russian émigrés arrived in Australia in the early 1920s. Principally, these were refugees from Siberia, who emigrated to Australia via China. The oldest community in Australia was founded in 1925, in Brisbane. This parish, which is dedicated to St. Nicholas, only had a small house chapel at first; but in 1926, it was able to have its own church. In 1933, this was replaced by a new structure. The new church was located on parish land, had a bell tower, and could accommodate some 200-300 faithful. After Australia was elevated to an independent diocese, in 1946, the St. Nicholas Church became the cathedral for the newly appointed bishop. Until 1950, the St. Nicholas Cathedral remained the residence of Bishop Theodore (Rafailsky). Then, between 1950 and 1953, after the episcopal residence had been transferred to Sydney, St. Nicholas Cathedral served as the cathedral of the vicar bishop of Australia. In 1963-64, Bishop Philaret was the vicar there, before he was elevated to Metropolitan and enthroned as the new First Hierarch of the Church Abroad. [5] Tserk. Zhizn´ (1936) 1, p. 17; Russ. Prav. Ts. 2, pp. 1318-1324, 1414-1415; Patock, Australien, pp. 183-187.

A second Russian émigré community has been in existence in Sydney since 1938. They had only a small house chapel dedicated to St. Vladimir. After 1950, most Russians settled in the Sydney area, so Archbishop Theodore decided to transfer his episcopal see to this city and used the small St. Vladimir chapel from 1950-1953 as his cathedral. The necessity of building their own cathedral became apparent when the small chapel could no longer meet the needs of the community. In 1950, the cornerstone for the Sts. Peter & Paul Cathedral was laid. Three years later, the new spacious church was consecrated. The conspicuous belfry towered above the church built in classical style. The three-tiered iconostasis was adorned with icons from the old St. Vladimir Chapel and completed with other icons by the iconographer N.I. Orlik. The iconostasis was finally completed in 1960. In 1965, three bells were blessed and the parish school was opened. It is attended by approximately 140 children and has eight teachers. The archbishop’s residence and the diocesan office were located in a small building behind the new cathedral during the early years; this building is now used as a parish center. The residence and offices were moved to a new building in 1960, in the Croydon section of the city. [6] Russ. Prav. Ts. 2, pp. 1325-1326, 1362-1367.

These two communities, in Brisbane and Sydney, remained the only Russian ones in Australia until 1945. They belonged to the church district of the Far East and were administered by the Bishop of Peking. There are very contradictory data on the number of faithful in Australia before 1945. Though mostly one reads of “small groups” and “a few émigrés,” there is a longer article in a 1937 Orthodox Russia that discusses the “blossoming parish life” in Australia. [7] Prav. Rus’ (1937) 7, p. 6. The article indicates that 37,000 Orthodox are supposed to have lived in Australia, New Zealand, and the surrounding islands. The interest in Orthodoxy would have been great. The Peking Ecclesiastical Mission, therefore, sent Archimandrite Theodore to Australia to organize parish life anew. He arrived in Australia in November 1935 and received permission from the Australian government to establish a monastery, which was supposed to serve as the center of the planned mission, because the prospects for a mission were to be great. Therefore, in Peking, there were plans to create a Diocese of Australia & New Zealand. An appeal was sent to the Synod, as well as to the entire diaspora, to support these plans with financial assistance.

Besides this report, there other announcements on the further development of the project followed. Why these plans were not carried out is unknown. Presumably, the statistical information referred to all the Orthodox of various nationalities, who lived there. Otherwise, there would be no way to explain why no further parishes of the Church Abroad were established until the end of 1948.

After 1948 the number of Russian immigrants to Australia grew dramatically. The refugees came from Europe and China. Already in 1946, the Synod resolved to send a bishop to Australia, who was supposed to take over the administration of the new communities, because numerous refugees wanted to emigrate to Australia. Bishop Theodore (Rafailsky) was entrusted with the rule thereof. In 1942, he had been consecrated Bishop of Taganrog of the Ukrainian Autonomous Church and had joined the Church Abroad in 1946. On account of difficulties with his visa, Bishop Theodore only arrived in Australia in 1948. At this time, there were already 16 priests and 3 deacons serving 11 parishes. [8] Ibid. (1950) 2, p. 15. There were approximately 5,000 Russian faithful in the new diocese. [9] Ibid., 18, p. 16. By early 1950, both aforementioned parishes in Sydney and Brisbane were joined by the following parishes: St. Nicholas Parish in Adelaide, the Holy Protection Parish in Melbourne, the Elevation of the Cross Parish in Hobart (Tasmania), the St. Seraphim of Sarov Parish in Brisbane, Sts. Peter & Paul Parish in Perth; and four parishes in New Zealand (Christ the Savior Parish in Wellington, the Archangel Michael Parish in Dunedin, the St. Nicholas Parish in Christchurch, and the Christ the Savior Parish in Auckland). [10] Russ. Prav. Ts. 2, pp. 1362-1441.

In February 1950, Bishop Theodore was granted the title of Archbishop of Sydney, Australia & New Zealand, and at that time he transferred his residence from Brisbane to Sydney. He remained head of the immense diocese until his repose in 1955. His successor was vicar bishop Sabbas (Raevsky) of Melbourne, who was elevated to archbishop in 1957 and ruled the diocese until 1970, when he retired on grounds of ill health. He reposed in 1976, in Sydney. His successor was Bishop Theodosius (Putilin), who was consecrated vicar bishop of Melbourne in 1969. Bishop Theodosius, since 1971 archbishop, ruled the diocese until 1980. After his death Bishop Paul (Pavlov), since 1981 archbishop, became the new head of the diocese.

In order to better administer the widely dispersed communities, a vicariate and two deaneries were created in 1950. The deaneries were located in Adelaide for southern Australia and in Melbourne for Victoria. Today the deaneries are centered in the cities of Sydney and Brisbane.

The vicariate was created in Melbourne and assigned to Bishop Athanasius (Martos). At this time, there were about 600 faithful living in the city. Because the Melbourne community did not have its own church, Bishop Athanasius resided in Brisbane, where the St. Nicholas Cathedral was located. After his appointment to the see of Buenos Aires & Argentina, the vicariate of Melbourne was transferred to Bishop Savva (Raevsky), who, however, in the very next year had to assume the rule of the Australian Diocese, because Bishop Theodore died. Bishop Savva’s successor was Bishop Anthony (Medvedev). He administered the vicariate of Melbourne from 1956-67 until he was appointed Archbishop of San Francisco & Western America. For two years, the vicariate remained vacant. In 1969, the long-time rector of the Sts. Peter & Paul parish in Perth, Archpriest Sergius Putulin, after he had taken monastic vows, was consecrated the new vicar bishop of Melbourne with the name Theodosius. Bishop Theodosius remained the administrator of the vicariate for barely two years. In 1970, he succeeded Archbishop Savva.

A second vicariate was established in 1963. Archimandrite Philaret, who had only shortly before arrived in Australia from Harbin, was in charge of the administration. Because the Synod of Bishops chose Bishop Philaret the following year to be the successor to the aged Metropolitan Anastasius, the vicariate of Brisbane remained vacant from 1964-67. Archimandrite Constantine (Essensky) was consecrated Bishop of Brisbane in 1967 and remained in this office until 1976. No successor was named for him. The churches of the vicar bishops of Brisbane and Melbourne have remained as cathedrals so that today there are three cathedrals in the diocese. The vicariate of Melbourne has had a spacious church since 1954, which the community had taken over from the Anglican Church. Approximately 2,500 people belong to the Melbourne cathedral parish, into which two smaller parishes were absorbed; the faithful were almost overwhelmingly émigrés from China, who came to Australia at the beginning of the 1950s. The parish school was at one time attended by 170 children. [11] Ibid., p. 1411.

The first diocesan assembly took place in December 1950, at which the importance of the new diocese was emphasized. In the diocese, there were two bishops and 24 clergymen, including three archimandrites, an archpriest, a hegumen, priests and deacons. There were references, however, also to the age of the clergy, of whom four were over 70 years old, another four were between 60 and 70 years old, eleven were between 50 and 60 years old, and only five were under 50. Therefore, Archbishop Athanasius proposed the establishment of a pastoral school in order to prepare possible candidates for the priesthood. [12] Prav. Rus’ (1952) 13, p. 9. There was also a suggestion to establish a monastery as a spiritual and religious center, the head of which was to be Archimandrite Theodore (Pudashkin). Also, the founding of kindergartens and schools was planned. [13] Ibid., (1951) 3, pp. 5-10; (1952) 2, pp. 14-15; Tserk. Zhizn´ (1952) 5-6, pp. 96-101; 7-8, pp. 141-45. The number of communities had, in the meantime, rose to 15, besides another 9 in camps to which the refugees had been evacuated. From 1949-1954, the diocese published its own journal, The Orthodox Christian (Pravoslavnyj Christianin), published by Bishop Athanasius. It was succeeded by The Word of the Church (Tserkovnoe Slovo). This journal has been appearing regularly since 1956 and is printed by the small diocesan press in Sydney. From 1967, there was also the journal, The Call (Prizyv), the printing of which has since had to be suspended.

The pastoral school was not established, due to a lack of financial funds and teaching staff. The desire to establish a monastery was pursued further, however, and in 1955 finally took on a concrete form. Two monks from Harbin, Hieromonk Demetrius and Hierodeacon Peter, obtained a 20-hectare plot of land, upon which the monastery was to be founded with the support of the diocesan administration, in the area of Kentlyn, near Campbelltown, some 30 miles from Sydney. The monastery was first supposed to undertake the care and organization of the refugees from Manchuria and China who, since the 1950s, were receiving exit visas to the West. The building of the monastery went forward. The main building, a long flat structure with monastic cells, a house chapel, and a few other rooms, was finished within a year. Then further building came to a standstill because the volunteer workers withdrew and the health of Hieromonk Demetrius did not permit further progress. The monastery was given to a few nuns, who were living in the Russian home for the elderly in Cabramatta. The nuns belonged to a group of nuns from the former Harbin convent of the Vladimir Icon of the Mother of God and had arrived in Australia a short time before. In the years following, the monastery was finished and extended by the addition of a few barracks, with financial help from America, from the Australian authorities, and from church and international agencies; refugees were supposed to be housed there. In the 1950s and 1960s, the particular significance of the monastery also lay in the fact that it essentially bore the responsibility of preparing the refugees for life in Australia and helped in assimilating these people into the economic life of Australia. Later, these refugee barracks were transformed into a hostel for pilgrims and a home for the elderly, which was cared for by approximately six nuns; between 20 to 30 people lived there. [14] Seide, Klöster im Ausland.

While the convent flourished from the time of its establishment, all plans to establish a monastery in Australia failed. In 1965, Schema-monk Gurius (Demidov) made an attempt and founded a hermitage dedicated to St. John the Baptist only a few miles from the convent. This hermitage has a small house with a chapel, cells for the monks and guest rooms. Besides Fr. Gurius, no one else joined the monastery. The hermitage has been abandoned since the mid-1970s. [15] Russ. Prav. Ts. 2, p. 1240 ff.

A new attempt was made in 1985. A few hours’ drive from Melbourne in the middle of the Australia wilderness, a skete dedicated to the Holy Transfiguration was founded. Great strides have been made in the building up of this skete. A chapel, as well as living quarters for the brotherhood and for guests, have been set up, and a small church has been started. At this time, three people belong to the brotherhood.

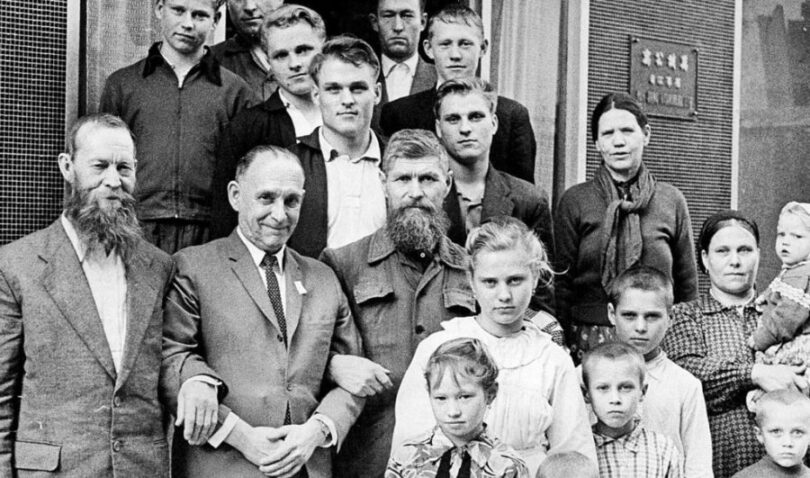

The Diocese of Australia & New Zealand deserves credit for helping the refugees from Manchuria and China. When they tried to obtain exit visas to travel to the West during the 1950s, the Diocese appealed to the Australian authorities on their behalf to issue entry permits to Australia. Bishop Savva devoted great attention to the refugees. On his initiative, the Diocesan Refugee Committee was established in 1956. Bishop Savva contacted the Australian authorities, the Refugee Committee of the United Nations, the World Council of Churches, and American institutions, and implored them for financial and moral help. The particular problem with these refugees lay in the fact that many were elderly: a group of 500 elderly people were waiting to enter Australia; in Harbin, another 5,000 people were waiting for exit visas, including 1,000 elderly. [16] Prav. Rus’ (1957) 8, pp. 14-15; (1958) 1, p.15; Anderson, pp. 4-6, 10-11. Shortly thereafter, there was another group, which included 600-700 elderly people. [17] Russ. Prav. Ts. 2, p. 1348. With the support of various institutions for the elderly people in need of nursing care, a few homes were established, in which between 10 and 50 people lived. Such homes are located in, among other places, Cabramatta and Campbelltown (near the convent), two in Melbourne, in Hillsville, in Sydney (Stratfield) and in Hamondville. In the course of its existence, the Refugee Committee cared for 4,000 people. [18] Tserk. Zhizn´ (1958) 1-6, pp. 32-33; Prav. Rus’ (1961) 9, p. 15. New Zealand also received large groups of refugees from China and Manchuria. Refugees were admitted beginning in 1948. The parishes, which still exist today, were founded by the former refugees from China. The aging of the immigrants has led in this decade to these communities becoming smaller and smaller because many of the parishioners have died. [19] Read, pp. 81-84.

Most parishes in Australia have their own churches, of which practically all have been built since 1948. In Australia at this time, there are still twenty parishes, in New Zealand four, and in Tasmania one. The New Zealand communities are cared for by Archpriest A. Godzhaev, and the one in Tasmania by Fr. M. Protopopov, from Blackburn. In 1980/81, the clergy of the diocese consisted of one bishop, four archpriests, one hieromonk, ten priests, three archdeacons, and one deacon. [20] Spisok (1981), pp. 31-32.

The largest church building complex was the Sts. Peter & Paul Cathedral in Sydney, to which the All Saints Church, with the episcopal residence and the diocesan administration in Croydon, also belong. Large churches were consecrated in Cabramatta (Holy Protection Church), in Adelaide (St. Nicholas Church) and near Blackburn (The Joy of All Who Sorrow Church). The Melbourne community was able to obtain a redundant Anglican church, the interior of which they adapted to their needs. Besides this church, a dozen or so smaller churches and chapels were built. The communities that exist today practically all have their own churches.

Besides these churches, the convent “New Shamordino” (now “Kazan’ Icon”), to which a home for the elderly is also attached, was systematically built up since 1956/57. Today, it serves as a place of pilgrimage for many of the diocesan faithful, who celebrate feast days together with the nuns in the monastery. The convent is supposed to be replaced in the coming years by a new building because the old wooden barracks are dilapidated due to termites and have become uninhabitable. For this reason, Archbishop Paul published an appeal in Orthodox Russia to the whole emigration for financial support. [21] Prav. Rus’ (1981), p. 12. With the support of state agencies and international organizations, it was possible to build numerous smaller homes for the elderly, whose residents were entrusted spiritually to the clergy of the diocese.

The larger communities have their own parish schools and libraries, lay sisterhoods and various youth groups. The diocesan newsletter has been appearing for more than 25 years and reports on the life of the diocese and the Russian Church Abroad.

References

| ↵1 | Prav. Rus’ (1968) 22, p. 12. |

|---|---|

| ↵2 | Ibid., (1972) 9, pp. 6-7; (177) 5, pp. 11-12. |

| ↵3 | Jahrbuch der Orthodoxie (1976/77) p. 188. |

| ↵4 | Ibid. (1972) 9, pp. 11-12. |

| ↵5 | Tserk. Zhizn´ (1936) 1, p. 17; Russ. Prav. Ts. 2, pp. 1318-1324, 1414-1415; Patock, Australien, pp. 183-187. |

| ↵6 | Russ. Prav. Ts. 2, pp. 1325-1326, 1362-1367. |

| ↵7 | Prav. Rus’ (1937) 7, p. 6. |

| ↵8 | Ibid. (1950) 2, p. 15. |

| ↵9 | Ibid., 18, p. 16. |

| ↵10 | Russ. Prav. Ts. 2, pp. 1362-1441. |

| ↵11 | Ibid., p. 1411. |

| ↵12 | Prav. Rus’ (1952) 13, p. 9. |

| ↵13 | Ibid., (1951) 3, pp. 5-10; (1952) 2, pp. 14-15; Tserk. Zhizn´ (1952) 5-6, pp. 96-101; 7-8, pp. 141-45. |

| ↵14 | Seide, Klöster im Ausland. |

| ↵15 | Russ. Prav. Ts. 2, p. 1240 ff. |

| ↵16 | Prav. Rus’ (1957) 8, pp. 14-15; (1958) 1, p.15; Anderson, pp. 4-6, 10-11. |

| ↵17 | Russ. Prav. Ts. 2, p. 1348. |

| ↵18 | Tserk. Zhizn´ (1958) 1-6, pp. 32-33; Prav. Rus’ (1961) 9, p. 15. |

| ↵19 | Read, pp. 81-84. |

| ↵20 | Spisok (1981), pp. 31-32. |

| ↵21 | Prav. Rus’ (1981), p. 12. |

You forgot to mention the fact that Archbishop Theodosius (Putilin) was previously priest of Sts Peter & Paul church in Perth, Western Australia, who, upon the death of his wife, became eligible for the post of Bishop and, later, Archbishop, of ROCOR in Australasia.

Some of the historical parish information is inaccurate.