The principal commemoration of the 1600th anniversary of the First Ecumenical Council was hosted by the Church of England. The high point was a celebration in Westminster Abbey on 29 June, 1925. Prominently participating in this historic occasion were the Patriarchs of Alexandria Jerusalem. No Orthodox Patriarch had ever been in England before. And from the Russian Church came to Westminster the famously conservative theologian, Metropolitan Anthony of Kiev. What compelled these deeply traditionalist prelates to make the onerous journey from distant lands to London? And what did the Anglicans hope to achieve with this celebration? After this remarkable event, Archbishop of Canterbury, Randall Davidson, commented, “The causes which led to the extraordinary fact that the Eastern prelates should come to England in order suitably to commemorate Nicaea would form an admirable subject for a thoughtful essay at the hands of anyone who is versed in ecclesiastical history and international politics.” An incisive observation: the causes which led to this “extraordinary fact” were indeed as much secular as they were ecclesiastical. [1] A detailed examination of how politics has influenced Anglican-Orthodox relations is to be found at Bryn Geffert, Eastern Orthodox and Anglicans (University of Notre Dame, 2020).

1. Unique Historic Event

Westminster Abbey, London. (photo credit: in the public domain)

The place: Westminster Abbey — that ancient church where for more than 1,000 years all English kings and queens have been crowned. The date: the feast of Saints Peter and Paul, Monday 29 June, 1925 — patronal feastday of Westminster Abbey. The occasion: the commemoration of the 1600th anniversary of the First Ecumenical Council, held in Nicaea in AD 325. The event: Choral Holy Communion.

The service commenced with three ceremonial processions into the sanctuary. First, 150 Anglican clergy of the Convocation of Canterbury; then the magnificently robed Orthodox clergy; and finally, the choir, and forty Anglican bishops. Amongst the Orthodox were Patriarch Photios (Peroglu) of Alexandria; Metropolitan Nicolaos (Evangelides) of Nubia; Patriarch Damianos (Kasiotes) of Jerusalem; Archbishop Timotheos (Themelis) of Jordan; Archbishop Germanos (Strenopoulos) of Thyateira. The Russian bishops comprised: Evlogy (Georgievsky), Metropolitan of Western Europe; President of the Acting Council of the Russian Bishops outside Russia, Metropolitan Anthony (Khrapovitsky) of Kiev; and Bishop Benjamin (Fedchenko) of Sevastopol. As the Orthodox delegation entered Westminster Abbey, the choir chanted the Orthodox liturgical greeting of an Eastern prelate, “From the rising to the setting of the sun.”

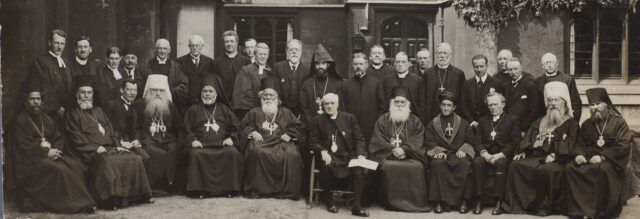

29 June, 1925, Westminster Abbey, London. 1600th Anniversary of the First Council of Nicaea.

1st l. Metropolitan Germanos of Thyateira; 4th l. Metropolitan Anthony of Kiev; 5th l. Archimandrite Theodossy, assistant to Metropolitan Anthony. (photo credit: Lambeth Palace Library)

The Orthodox delegation made a great impression, “with its many vestments of cloth-of-gold and the jewelled orders of the two Patriarchs.” [2] “The Council of Nicaea. Sixteenth Centenary Celebrated in Westminster Abbey,” Onward. 11 July, 1925, 207.

At the Westminster service, and at the multiple Anglican services which they attended while in England, the bishops (except Metropolitan Anthony) wore vestments which they would normally wear when attending an Orthodox liturgical service, including most noticeably the mantiya (episcopal mantle). For example, at Winchester Cathedral in the previous week,

The Metropolitan Germanos wore a mantiya of bright blue-purple thickly edged with deep gold, the Metropolitan Evlogy, a mantiya of plum colour embroidered with golden leaves and flowers, and Bishop Benjamin a mantiya of plum colour adorned with stripes of white and red. Each Metropolitan carried his own staff – not a shepherd’s crook like our Western staves, but with the head crowned by two serpents surmounted by a cross. [3] “Eastern Prelates in England.” Church Times. 26 June, 1025. 781.

Given that the canons of the Orthodox Church expressly forbid clergy from entering into joint prayer with schismatics and heretics, the wearing of liturgical vestments at such events seems to be defiantly contrary to the spirit of those canons. However, there have been multiple exceptions, not least of which were witnessed many times in England and Wales in the summer of 1925.

Amongst the 2,000-strong congregation in the nave was a place reserved for members of the Greek, Russian and Balkan communities in London, as well as the retinues which had accompanied the bishops from abroad. [4]including Prof. H. Alivizatos (Church of Greece); Archpriest Radu (Romanian Patriarchate); Principal Secretary of the Russian Exile Council, Evkustodion I. Makharoblidze, and Professor of New … Continue reading They were joined by His Holiness Mar Eshai Shimun XXIII, the hereditary Catholicos-Patriarch of the Assyrian Church of the East, who, at that time 17 years of age, was being educated at St Augustine’s College, Canterbury.

The Westminster Abbey choir sang the service of Holy Communion according to a setting by Palestrina. There was a lengthy sermon by Randall Davidson, Archbishop of Canterbury, and then Photios, Patriarch of Alexandria, was escorted by Canon John A. Douglas to the front of the altar and, facing the people, the Patriarch recited “in a loud resonant voice” [5] .D., “The Patriarchs at the Abbey,” Church Times, 3 July,1925. 25. the Nicene Creed in Greek without, of course, the filioque. When it came to the prayer of consecration, the Orthodox prelates and other clergy removed their headgear and remained with their heads bare until after the final blessing, given by the Archbishop of Canterbury. The only people to receive the Holy Communion were Anglican clergy already located in the sanctuary.

Later that year, recalling the Nicaean commemoration at Westminster, the Anglican Bishop, Charles Gore, said,

There has been nothing like it since the Great Schism. You may remember the intense thrill of the silence which passed over the great congregation in Westminster Abbey when the Patriarch stood out and recited the ancient Creed in its ancient language… [6] “The Late Patriarch of Alexandria,” Church Times, 13 November,1925. 574.

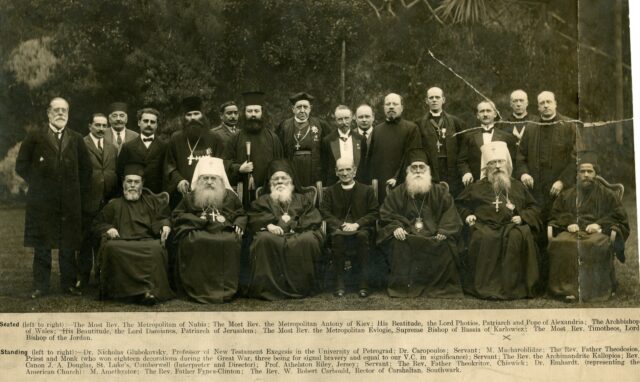

29 June, 1925 , Westminster Abbey, London. 1600th Anniversary of the First Council of Nicaea.

Seated: Professor N. Glubovsky, Canon H. de Candole, Canon Charles, the Romanian Fr Radu, Bishop Benjamin of Sebastopol, Archbishop Timotheos of the Jordan, Metropolitan Anthony of Kiev, Patriarch Damianos of Jerusalem, Patriarch Photios of Alexandria, Archbishop Randall Davidson of Canterbury, Canon Carnegie, Mar Eshai Shimun, Metropolitan Germanos of Thyateira, Metropolitan Evlogy of Western Europe, Metropolitan Nicolaos of Nubia, Canon Donaldson, Canon Storrs, Professor H. Alivisatos, E. Makharoblidze, Canon J. Douglas. (photo credit: Lambeth Palace Library)

2. Origins of the Nicaean Commemoration

It would be reasonable to suppose that the 1600th Nicaean Commemoration would be held not in London but in Nicaea (İznik, Turkey) and hosted by the Patriarchate of Constantinople. Alas, that was not possible. The Greco-Turkish War of 1919-1922 led to a Turkish war of aggression against the Greek communities in Asia Minor, including genocide, massacres, forced deportations as well as the destruction of hundreds of Greek Orthodox monuments, including in 1922 the Church of the Dormition, the principal church of Nicaea. Between 1923 and 1925 there was turmoil in the Patriarchate, caused principally by the politics of Turkey and Greece, resulting in the tenure of no less than three different patriarchs within two years. In November, 1924, John Greig, the Anglican Bishop of Gibraltar, visited the Phanar in Constantinople. Patriarch Gregory VII had suffered a massive heart attack and was mortally sick. Bishop Greig instead met with Metropolitan Kallinikos of Kyzikos, who confidently predicted that there would be a Nicaean celebration in Constantinople. [7] John Greig, Report to the Archbishop of Canterbury’s Eastern Churches Committee, 1924. Bell 198, ff. 94-96, Lambeth Palace Library (LPL).

Just why it was necessary to commemorate the Council of Nicaea on its 1600th anniversary has never really been answered by anybody, except, perhaps, that we all like celebrating anniversaries. In fact, the Orthodox Church has never forgotten the First Ecumenical Council: every year She celebrates the liturgical Feast of the First Ecumenical Council on 29 May. However, it became clear that, given the political situation in Turkey and the death of Patriarch Gregory VII in November, 1924, it would be impossible for his successor to host such a commemoration.

There was also a suggestion that the Patriarch of Jerusalem might stage a 1600th commemoration event but, as we shall learn, that possibility was out of the question due to the restrictions placed on the Jerusalem Patriarchate by the ruling British Mandate. The journal of the Patriarchate of Alexandria, Pantaenos, summarised the situation:

The commemoration of this important event had been considered by the Eastern Church, and, indeed, had been announced as to be celebrated by an Œcumenical Synod in Jerusalem, but, unhappily, for reasons familiar to all, that project had been abandoned. [8] cited by J. A. D., “The Visit of the Patriarchs,” Church Times, 24 July, 1925. 103.

It was in this context of uncertainty that Canon John A. Douglas [9] Canon John Albert Douglas (1868 – 1956) John and Charles Douglas accessed January, 2025. of the Church of England spotted an opportunity and exploited it to the full.

3. Preparations

For many years Canon Douglas had been cultivating warmer relations between the Eastern Orthodox and the Church of England. As a founder of the Anglican & Eastern Churches Association (A&ECA), [10]The Eastern Church Association was founded in 1864. In 1914, it adopted the name A&ECA when it merged with the Anglican and Eastern Orthodox Churches Union, a merger that was arranged between the … Continue reading he was a leading member of the Archbishop of Canterbury’s Eastern Churches Committee. Fully supportive of Canon Douglas in staging the Nicaean Commemoration was the Bishop of London, Arthur Winnington-Ingram. The conventional date for commemorating the First Ecumenical Council is 29 May. [11]However, see Y. R. Kim (ed.), Cambridge Companion to the Council of Nicaea (Cambridge University Press, 2021). 96. Here 20 May is suggested, following the 5th century historian, Socrates of … Continue reading However, the Anglicans decided to hold the commemorative event on St Peter’s Day, 29 June, 1925.

Late in March, 1925, Canon Douglas started to sound out various Orthodox clergy about their willingness to attend the Westminster event. His list of potential invitees was quite modest. First and foremost, he wanted to invite from Belgrade Metropolitan Anthony, head of the Russian Orthodox Church in Exile, together with the Greek Metropolitan, Germanos of Thyateira, who lived in London. The Canon also thought he would invite representatives from: the Serbian and Romanian Churches; the Church of Greece; and the Armenian priest in London. He took it upon himself to send a personal invitation to Metropolitan Anthony early in April. [12] J. A. Douglas, letter to Anthony (Khrapovitsky), April, 1925. Douglas 26, f25. LPL. However, in mid-April he then left the matter of the remaining invitations in the hands of the Bishop of London, while Canon Douglas led a group of some 200 Anglicans on a six-week pilgrimage in the Middle East. He and the pilgrims were away until the middle of June. On returning to London, Canon Douglas was horrified to learn that the Bishop of London had invited all the Orthodox Patriarchs and, even worse, two of them had accepted — Patriarch Photios of Alexandria and Patriarch Damianos of Jerusalem. Why was Canon Douglas so upset? Because he knew that the A&ECA would have to fund all the costs, not just of the Patriarchs but of their entourages. Further, he knew from his own experience, these two Patriarchs had their own motivations for wanting to come to London and, as we shall see, celebrating Nicaea was not at the top of the agenda for either Patriarch.

Thus, Canon Douglas was unexpectedly landed with the cost of financing and hosting some 20 Orthodox visiting clergy and their assistants. The actual commemoration date was going to be 29 June but inevitably the visitors, travelling vast distances, started arriving well before that. In fact, the Nicaean programme began on 17 June when Metropolitan Germanos received an honorary Doctorate in Divinity at Oxford University. The Nicaean programme ended on 21 July when the two Patriarchs called on the Archbishop of Canterbury to make their farewells.

Canon Douglas faced several challenges, the greatest of which involved the filioque. The central act of worship in the commemoration was going to be Choral Holy Communion in Westminster Abbey. He felt that it would be intolerable for the Orthodox delegates to hear the Nicene Creed recited with the filioque. He asked the Archbishop of Canterbury to give a ruling, but Archbishop Davidson directed him to the Dean of Westminster. Most of the clergy of the Chapter of Westminster Abbey (the ruling body) were of an evangelical persuasion and would brook no interference in the wording of the Creed as found in the Book of Common Prayer. After two months of lobbying by Canon Douglas, a compromise was reached. The Nicene Creed would be recited, first in English (with the filioque), and then in Greek (minus the filioque) and only by one of the visiting bishops — Patriarch Photios as it turned out.

4. Before and After

A week before the Westminster Abbey service, Metropolitan Germanos, Metropolitan Evlogy, and Bishop Benjamin, accompanied by several Orthodox priests and deacons, made an official visit to Canterbury Cathedral. On the next day, the visitors were in Chichester. Here there was a procession from the Theological College to the Church of Saint Bartholomew where, at the conclusion of Evensong, Metropolitan Evlogy gave the blessing. Later in the evening they attended Compline in the College Chapel, after which each prelate gave his blessing, and the Russian ecclesiastics sang a hymn in Slavonic before the altar. On the next day they attended High Mass, followed by another procession to Chichester Cathedral. Here the Orthodox clergy chanted Dostoinoe Est’ (a hymn in Church Slavonic to the Mother of God). Then the visitors travelled to Winchester Cathedral. They were greeted with another grand ceremonial entrance and, at the conclusion of Evensong, Metropolitan Germanos gave the blessing.

On the next day, the Orthodox prelates and clergy attended High Mass at Winchester Cathedral. After the Gospel had been sung in English,

…the Protodeacon Theokritoff holding the Russan Gospel Book, having been solemnly blessed by his Archbishop, the Metropolitan Evlogy, sang the Russian Gospel for the Sunday. The Protodeacon was a splendid figure in his cloth-of-gold sticharion and his scarlet and gold orarion… The Gospel was preceded and ended by the response of the Russian Liturgy, corresponding to our own ‘Glory be to thee, O Lord,’ sung by the Russian ecclesiastics present… After the English blessing by the celebrant, the Metropolitan Evlogy, having made his reverence to the Blessed Sacrament, gave the blessing in Slavonic. [13] “Eastern Prelates in England,” Church Times, 26 June,1925. 781.

And so, the Orthodox caravan made its way to Salisbury Cathedral and thence to Exeter, where they were joined by Metropolitan Anthony of Kiev who had just arrived in England from Serbia. At each Anglican Cathedral, the Orthodox bishops and other clergy were ceremonially welcomed and all participated in the Anglican services. They arrived back in London on the evening of Sunday, 28 June.

29 June, 1925 , Westminster Abbey, London. 1600th Anniversary of the First Council of Nicaea.

Seated: Archbishop Timotheos of the Jordan, Archbishop Nicolaos of Nubia, Professor H. Alivisatos, Metropolitan Anthony of Kiev, Archbishop Germanos of Thyateira, Patriarch Photios of Alexandria, Archbishop Randall Davidson of Canterbury, Patriarch Damianos of Jerusalem, Mar Eshai Shimun, Archbishop Nathan Soderblöm of Uppsala, Metropolitan Evlogy of Western Europe, Bishop Benjamin of Sebasapol.

Standing: Revd. M. G. Haigh, Revd. R. F. Borough, Revd. H. de Candole, Patriarch Photios’s attendant, Prebendary J. H. Ellison, Sir W. Dickinson, Archdeacon P Stacy Waddy, unknown, Canon C. Jenkins, Professor N. Glubovsky, Vardapet Goussan Nazarian, Fr Radu, Canon J. A. Douglas, Bishop James Darlington of Harrisburg, USA, Revd. E. M. Bickersteth, Bishop John Greig of Gibraltar, Commander H. C. Luke, Canon F. N. Heazell, Mr. Athelstan Riley, Revd. Turner. (photo credit: Lambeth Palace Library)

Following the 29 June Westminster service, over a period of three weeks the Orthodox visitors attended numerous services and other events. Highlights included: a visit to the British Museum; a visit to a convent at Clewer; [14]“It was noteworthy that here [at Clewer] as elsewhere the Patriarchs and other bishops rendered adoration to the Blessed Sacrament in the manner customary in their own Church i.e. with profound … Continue reading Evensong in Southwark Cathedral (at which Bishop Benjamin, Fr Vladimir Timotheieff and Deacon Vladimir Theokritoff chanted Slavonic hymns) ; a Civic Reception held by the Mayor of Southwark; a visit to the British & Foreign Bible Society; a visit to Eton College where the Patriarchs chanted a paraklesis at the High Altar; a visit to Oxford including a garden party; attendance at a meeting of the Archbishop of Canterbury’s Eastern Churches Committee at the House of Lords; a meeting arranged by ‘The Appeal for the Russian Clergy’ at King’s College, London; a meeting of the Anglo-Catholic Congress at the Albert Hall; a Lambeth Palace garden party; and a visit to the headquarters of the Church Army. Here the Patriarch of Alexandria told the assembled workers and catechists that

he was present, not as a Patriarch, but as a fellow-worker in the Gospel of Christ and warmly commended their work. Prayers and singing followed and the two Prelates gave their blessing. [15] J. A. D., “The Visit of the Patriarchs,” Church Times, 24 July,1925.103.

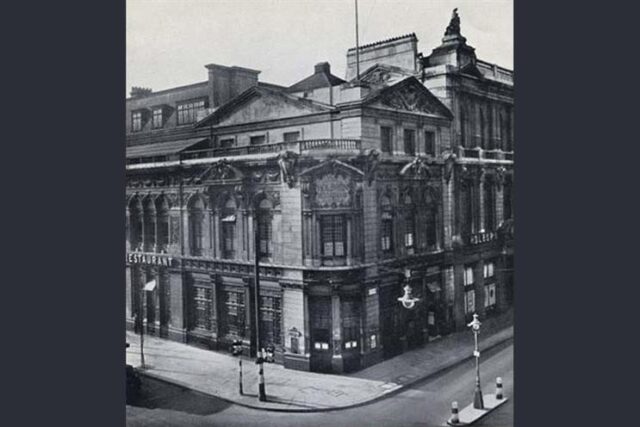

The Holborn Restaurant, London: here on 7 July, 1925, there was held a formal banquet of welcome to the Orthodox visitors, attended by 600 guests. Opened in 1874, the Holborn Restaurant was regarded as one of London’s grandest and billed as adding “a spice of poetry to the dull prose of everyday life”. (photo credit: in the public domain)

Apart from the actual commemoration service at Westminster, the major highlight was on Tuesday, 7 July at the Holborn Restaurant, London, — a formal banquet of welcome to the Orthodox visitors, attended by 600 guests. [16] “The Patriarchs in England.” Church Times, 10 July,1925. 55.

The Earl of Selborne presided, supported by the Archbishops of Canterbury and York. Apart from the Eastern delegation, guests included thirteen Anglican bishops, several Lords, several MPs, the Greek Ambassador, the Lutheran Archbishop of Upsala, and Mar Eshai Shimun. Proposing the toast of the guests, the Archbishop of Canterbury mentioned a meeting on that same day in the House of Lords: the Anglican bishops had met with “Their Beatitudes and other ecclesiastics from the East,” and that meeting had made him hopeful of the nearer approach of reunion.

Both Patriarchs replied to the toast, their speeches being translated by M. Ioannides Gennadius, formerly Greek Ambassador in London. The Patriarch of Alexandria said that he was hopeful, indeed certain, that the meetings in London would bring about the desired results, particularly as the basis of unity was the creed of Nicaea. The Patriarch of Jerusalem said that the Orthodox delegation had realized that it was “the Christian faith of the English nation that was responsible for its greatness, its progress and its nobility.” Unceasing prayers would be offered in Jerusalem that God would bless the English nation and the English Church. A government minister, Sir Samuel Hoare, spoke in fluent Russian at length about the martyred Church in Russia. [17] Sir Samuel Hoare (1880-1959) from 1916 to 1917 was head of the British Intelligence Mission to the Russian General Staff. In that post, he reported the death of Rasputin to the British government.

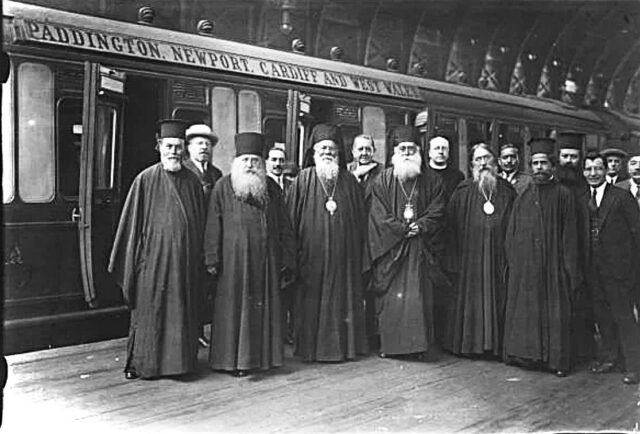

Group of Orthodox particioants wait to board a train for a journey to St. David’s where they will attend the 16th centenary of the Council of Nicaea. (Photo courtecy: Ryan Thompson)

Responding to Sir Samuel Hoare, Metropolitan Anthony reminded the guests that the One, Holy, Catholic and Apostolic Church cannot be divided. He talked about Christian communities and confessions which make friendly moves towards the Orthodox Church and the canons which are applicable to such situations. Based on his belief in the confessional closeness between the Anglican Church and the Orthodox Church, the Metropolitan declared,

If any Anglican bishop or clergyman wished to enter the Orthodox Church, then he could be received by the third rite, that is to say, without his ordination being repeated or, in other words, he could be received in his orders. [18] C. J. Birchall, Embassy, Emigrants, and Englishmen (Holy Trinity Publications, 2014). 236. For further consideration of the views of Metropolitan Anthony: see section 8 below.

The thunderous applause with which the Metropolitan’s remarks were met will be explained in section 9 below: Recognition of Anglican Orders.

St. David’s Cathedral, west Wales. In the east wall of the Lady Chapel is a small recess containing a casket which contains the relics of St David and St Justinian. (photo credit: in the public domain)

From 13 to 15 July the Orthodox visitors visited the ancient city of St. David’s in west Wales. The Dean of St. David’s, W. Williams, stated, “our Cathedral here is more closely connected with the Eastern Churches than any other in the Kingdom.” [19] Letter from W. Williams to A. Riley, 30 May, 1925. Douglas 26, f264. LPL. The Cathedral houses the relics of St. David who, it is believed, was consecrated bishop in the 6th century by a Patriarch of Jerusalem. The Orthodox bishops and priests again participated in a special service for the Nicaean Commemoration. During the Thanksgiving service there was a fourfold affirmation of the Nicene Creed: it was first said in Welsh, then sung in English (complete with filioque); then it was recited alone in Greek by Patriarch Photios and finally chanted by the Russians in Slavonic. This was followed by a ‘Public Function of Social Welcome’ in the Bishop’s Palace Grounds, attended by 300 guests.

14 July, 1925, St David’s, Wales. 1600th Anniversary of the First Council of Nicaea. (photo credit: Lambeth Palace Library)

In between all these events, the Orthodox clergy managed to visit their own flocks in London and in Oxford. The two Russian Metropolitans visited several times Russian House in Cromwell Road, London, where Metropolitan Anthony delivered lectures: on Patriarch Nikon, and on the restoration of the Patriarchate. On Sunday, 5 July, the two Patriarchs were present in the Russian Church during Divine Liturgy which was served by Metropolitan Anthony, assisted by Metropolitan Evlogy and Bishop Benjamin. Metropolitan Evlogy spoke words of welcome to the two Patriarchs, who stood outside the iconostasis. Patriarch Photius replied, thanking him for his kind words and observed that,

…even in poverty the Russians found the means to adorn their churches magnificently. Such people, he said, could not disappear, but God would give them rebirth. The Patriarch expressed his joy at seeing a spir

itual leader at the head of the emigration — Metropolitan Anthony, who was a zealot of Orthodoxy and a most learned hierarch. Through him the Patriarch conveyed his best wishes to the Russian exiles and extended his blessing to them. [20] Birchall (Embassy). 237.

On the following day, during a visit to the Anglican Cowley Fathers in Oxford, the Russian bishops served Divine Liturgy in the Cowley Church. On Sunday, 12 July, Patriarch Damianos, together with Metropolitan Anthony, served Divine Liturgy at the Greek Cathedral in Moscow Road, while Metropolitan Evlogy served Divine Liturgy at the Russian Church in Victoria. On 17 July, Metropolitan Anthony served a panikhida in the Russian Church for the repose of the souls of the martyred Emperor Nicholas II and his family. Metropolitan Anthony and Metropolitan Evlogy also visited several Anglican Churches. For example, on 19 July, accompanied by Archpriest Vasily Timotheieff, [21] Fr Vladimir had been elevated to the rank of Archpriest by Metropolitan Evlogy on the previous Sunday. both Metropolitans attended the patronal festival services at the extreme Anglo-Catholic parish of St. Silas, Pentonville (north London), even taking part in Solemn Evensong and Benediction. [22] Benediction is a Latin rite in which Jesus Christ is said to be adored in the consecrated Host exposed on the altar.

By the end of July all the Orthodox visitors had departed and the hosts of the 1600th Centenary Commemoration in London were left to ponder what the outcome might be.

5. Glaring Problems

Three days after the Westminster event, the Russian priest in London, Father Vassily Timotheieff, wrote to Canon Douglas:

The Prelates and the Professors are appreciating very much everything you have arranged for them, but they are struck with one feature — so far, they have had only pleasure, and they seem to be wanting/expecting also some serious work. Do you think it would be possible to arrange for them a sort of unofficial conference to discuss (a) general possibilities of the re-union and (b) some special points. [23] Letter from V. Timotheieff to J. Douglas. Douglas 26, f201. LPL.

Canon Douglas was aghast at the suggestion. After all, if the proposed Conference turned to theological matters, this would bring into sharp relief again the reality that the Anglo-Catholics [24]Anglo-Catholics emphasize the Catholic rather than the Protestant heritage of the Anglican Church. Anglo-Catholics are sometimes called “high” church people, in that they give a “high” place … Continue reading were a minority in the Church of England and that most Anglicans would not find themselves in agreement with the Anglo-Catholics, let alone with the Orthodox. He wanted to avoid theological discussions at all costs. Another serious concern for Canon Douglas was that in any formal discussions the differences which existed between the Orthodox might become glaringly exposed. The 1923 reforms of the then Patriarch of Constantinople, Meletios IV, especially Calendar Reform, were deeply contentious. At Westminster, the Orthodox delegation was sharply divided, with the two Patriarchs and Metropolitan Anthony against the reforms and the remainder broadly in favour. Canon Douglas wrote to Bishop Gore,

My nightmare is that they [the Orthodox] may violate our hospitality and consume their quarrel here. The Patriarchs are old men and neither quick of comprehension nor familiar with our mentality and atmosphere. [25] Letter from J. Douglas to C. Gore. Douglas 26, ff.202. LPL.

Canon Douglas proposed that the bishop might chair such a Conference, and described in detail how the Conference should become a series of prepared statements, not a discussion at all. The Conference did take place on the following Tuesday when the Orthodox delegation attended a meeting of the Archbishop of Canterbury’s Eastern Churches Committee.

6. The Patriarchs

What was it that motivated the Patriarchs of Alexandria and Jerusalem to come to London, to stay for a month or so, and participate in numerous acts of Anglican worship? Neither were known previously for having the remotest interest in uniting the Anglican and Orthodox Churches. Each bishop had slightly different but connected motivations.

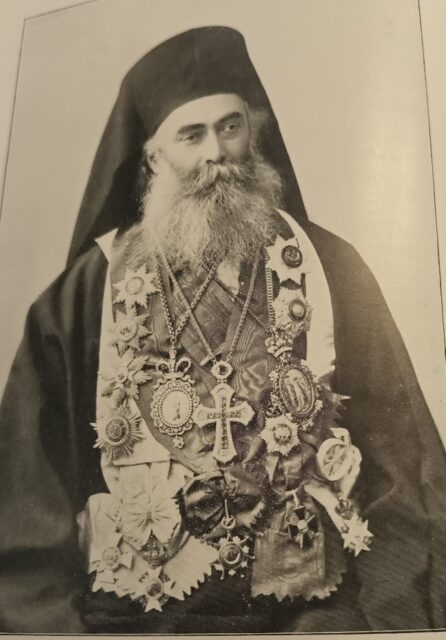

Patriarch Damianos I

Patriarch Damianos I of Jerusalem. (photo credit: The Christian East, May, 1924)

The delegation from Jerusalem was led by Damianos I (Kasiotes), Patriarch of Jerusalem and President of the Confraternity of the Holy Sepulchre, accompanied by Archbishop Timotheos (Themelis) of the Jordan, [26] Damianos I (1848 – 1931) was Greek Orthodox Patriarch of Jerusalem from 1897 to 1931. Archbishop Timotheos (1878 – 1955) was Greek Orthodox Patriarch of Jerusalem from 1935 to 1955. who had been educated at Oxford University and was a fluent speaker of English.

What was it that prompted the Patriarch in his 77th year to accept the invitation to make the arduous journey to London? Canon Douglas was certain as to the Patriarch’s motivation. To Commander H.C. Luke, Assistant Governor of Jerusalem, he wrote, “Damianos [has] undoubtedly come with a mind set on going for Betram.” He continued, “I am very nervous lest unpleasant incidents should occur.” [27] Letter from J. Douglas to H. Luke, 19 June, 1925. Douglas 26, f80. LPL. And to Sir Stephen Gaselee at the Foreign Office Canon Douglas wrote, “[the two Patriarchs] are coming to London with the intention of making a great row and of attacking Sir Anton Bertram and his two commissions.” [28] Letter from J. Douglas to S. Gaselee, 19 June, 1925. Douglas 26 f86. LPL.

“A mind set on going for Bertram” referred to the fact that the British Government [29] The Mandate for Palestine was a League of Nations mandate for British administration of Palestine and Transjordan. Britain administered Palestine from 1920 to 1948. had appointed the former Chief Justice of Ceylon, Sir Anton Bertram, to investigate and remedy the parlous state of the Patriarchate of Jerusalem. [30]for a detailed account, see K. Papastathis, “Diplomacy, Communal Politics, and Religious Property Management: The Case of the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem in the Early Mandate … Continue reading In the early 1920’s the Jerusalem Patriarchate owned some 600 properties, both in Palestine and abroad; a third of the land area of the Old City of Jerusalem was held by the Patriarchate. However, revenues had declined disastrously due to several factors: World War I had led to a cessation of pilgrimage; Russian financial support had been cut after the 1917 Revolution; poor administration; and, not least, endemic corruption. The Patriarchate had borrowed huge sums of money at high interest rates; patriarchal property was in danger of being confiscated. Consequently, the British Mandate put the Patriarchate into administration, and that administration, which saved the Patriarchate from bankruptcy, was being run by Bertram. In 1921 Betram had published his first report which was hugely embarrassing for the Patriarch. It highlighted the fact that the debts of the Patriarchate were estimated to be £556,000 — about £30 million in today’s values. [31] A. Bertram, & H. C. Luke, Report of the Commission Appointed by the Government of Palestine to Inquire into the Affairs of the Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem (Oxford University Press,1921).

Initially Patriarch Damianos had been supportive of British involvement in the affairs of the Patriarchate because he needed British protection from his detractors, including the Greek government, who otherwise would have had him removed from office. However, even by 1922 the Patriarch deeply resented British control since he was unable to access the Patriarchal revenues. After a visit to Jerusalem in 1922, Bishop Charles Gore reported to the Eastern Churches Committee,

The Patriarch Damianos is out to maintain his autocratic authority, on what he claims to be the monastic principle. He is in a state of violent indignation against the Government Commission on the patriarchal revenues, which is presided over by Sir Anton Bertram, of whom I saw a great deal, himself a sympathetic well-wisher of the Orthodox Church almost above all others. The very existence of the Commission [the Patriarch] represents as an unauthorized intrusion upon his spiritual domain. [32] C. Gore, “Memorandum for the Eastern Churches Committee.” MS2627, ff112-115. LPL.

Patriarch Damianos had demanded the opportunity to travel to London to speak to Bertram’s superiors, but he was refused permission. Then, unexpectedly, in May, 1925, the Bishop of London sent him an invitation to attend the Nicaean celebrations. This was the answer to a prayer and the Patriarch accepted with alacrity.

While in England the Patriarch diligently attended a multitude of ecumenical events for nearly a month. However, he also pursued relentlessly his wish to speak to Betram’s superiors at the Foreign Office. He also tried to get a meeting with the Earl of Balfour, author of the 1917 Declaration in support of a home for the Jewish people in Palestine, but Balfour absolutely refused to meet the Patriarch.

On 10 July, the plan of Patriarch Damianos succeeded to the extent that he was granted a meeting at the Foreign Office with Leo Amery, Secretary of State for the Colonies (in effect, the UK’s Minister for managing the British Empire). Despite the Patriarch’s intervention, Sir Anton Bertram remained undaunted and a year later proceeded to publish his second, highly critical, report. [33]A. Bertram & J. W. A. Young, Report of the Commission Appointed by the Government of Palestine to Inquire and Report Upon Certain Controversies Between the Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem and … Continue reading

In preparation for an audience with the King, the Foreign Office warned Canon Douglas,

His Majesty is not desirous of discussing ecclesiastical affairs with the Patriarch [of Jerusalem], the audience being in the nature of a courtesy extended to the Patriarch of Antioch and to the Patriarch of Jerusalem… Mr Amery trusts that you will impress upon the Patriarch of Jerusalem the necessity of avoiding controversial matters into the conversation would, in view of the King’s expressed desire to the contrary, naturally be extremely repugnant to His Majesty. [34] Letter from A. Edgcumbe to J. Douglas, 11 July, 1925. Douglas 26, f249. LPL.

On 20 July, both Patriarch Damianos and Patriarch Photios were received at Buckingham Palace. Following an audience with King George V, the Patriarchs were entertained to lunch with both the King and with Queen Mary.

A few days after the visit to Buckingham Palace Patriarch Damianos and Archbishop Timotheos began their long journey back to Jerusalem.

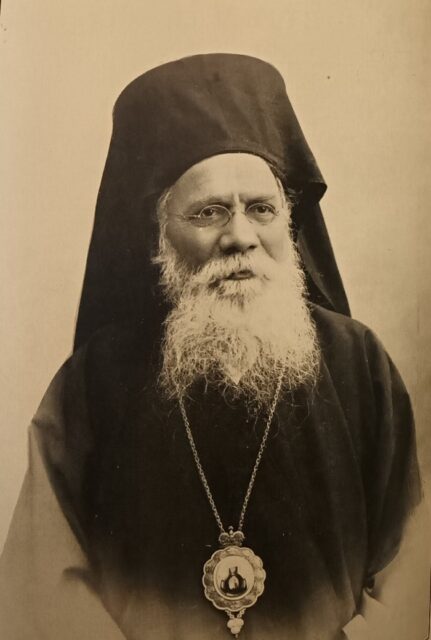

Patriarch Photios

Patriarch Photios of Alexandria. (photo credit: The Christian East, September, 1925)

When the second most senior bishop in Christendom, the direct successor to Saint Mark and Saint Athanasius, His Beatitude Photios (Peroglu), Pope and Patriarch of Alexandria, [35] “and of All Africa” was added to the Alexandrian title after 1927. arrived in London, he was accompanied by Nicolaos (Evangelidis), Metropolitan of Nubia, as well as the Patriarch’s personal physician, Dr. Karapoulos.

Patriarch Photios had a reputation of being the most conservative of the Greek Patriarchs. Canon Douglas publicly described the Patriarch as being “a strictly conservative theologian.” [36] J. A. D., “Death of Photios Patriarch and Pope of Alexandria.” Church Times, 11.9.1925. 283. In a private letter to Bishop Gore, Canon Douglas more colourfully described Patriarch Photios as “the most stubborn of conservatives.” [37] Letter from J. Douglas to C. Gore. Douglas 26, f202. LPL. The exact quotation reads, “We have two of the most stubborn conservatives here in Photios and Anthony, and Glubovsky is not a liberal!” Bishop Gore commented, “The tradition of Anglicanism in his country had generated in his mind a great suspicion of England.” [38] “The Late Patriarch of Alexandria.” Church Times, 13 November, 1925. 574. However, apparently it was not always so.

Fifteen years earlier, Patriarch Photios had come into contact with self-styled “Archbishop,” A. H. Matthew (1852-1919), an Englishman who was a former Roman Catholic priest. After leaving the Roman Church, Mathew had married and become the father of three children. Between 1908 and 1911 Mathew was a bishop of the Old Catholic Church of Utrecht. Pope Pius X excommunicated Mathew in 1911, by which time Mathew had become the self-appointed leader of a tiny English sect, comprising seven “bishops” and no more than 100 people.

It was while on a visit to England on a fund-raising mission in February,1911, that the Greek Orthodox Archbishop Gerasimos (Messara) of Beirut met Mathew and agreed to receive Mathew’s “English Catholic Church” into union with the Patriarchate of Antioch. [39] Anson, P. Bishops At Large. (Faber, 1964) 185-187; “Bishop Mathew and the Orthodox”, The Glastonbury Bulletin, 64. May, 1982. 197-206. However, within weeks the Archbishop of Canterbury had sent the Anglican Bishop of London urgently to Damascus where he personally secured an agreement from the Patriarch of Antioch to annul the agreement.

Meanwhile, Matthew wrote to Patriarch Photios in Alexandria, asking for union between his so-called “Western Orthodox Catholic Church” and the Patriarchate of Alexandria. On 26 February,1912, Patriarch Photios replied to the “Archbishop and Metropolitan of the Western Orthodox Church,” accepting him and his flock into union with the Patriarchate of Alexandria. The Patriarch granted them permission to use the Latin rite, omitting the Filioque, so long as the faithful recognized the canonical ordinances of the seven Ecumenical Councils. Within a few months this accord was forgotten, and “Western Orthodox Church” was dropped by Matthew as one of his many and elaborate titles. By the time Patriarch Photios visited London in 1925, “Archbishop” Matthew had been dead for six years, and there is no record of the Patriarch meeting with Matthew’s successor.

It is reasonable to ponder: in 1925 why did the Patriarch, by now so famed for his conservative theological stance, decide to go all the way from Egypt to London for an ecumenical celebration in London?

In the view of Canon Douglas, it was quite simple. Patriarch Photios went to London to support Patriarch Damianos in making trouble for Sir Anton Bertram and his unwanted Commissions. When Anglican Bishop John Greig had visited Alexandria in May, 1925, Patriarch Photios had raised the matter with Bishop Greig, asking that he make known the Patriarch’s disquiet to the Archbishop of Canterbury. Patriarch Photios expressed his fierce opposition to the British Commission of Financial Control in Jerusalem. He was also firmly against the reputed intention of Sir Anton Betram to remodel the Organic Law of the Confraternity of the Holy Sepulchre and of the Patriarchate.

Additionally, the 72 year-old Patriarch Photios suffered from a heart condition and wanted the opportunity to consult European doctors. The Anglican invitation included a promise of paying all travel expenses, an added incentive for going to London.

There was another factor: Turkish oppression and ethnic cleansing, wreaking havoc on the martyred Greek community of Turkey, was at the forefront of the minds of all Greeks who were living in an Islamic country. Could the same happen in Egypt, now that — at least nominally — the British were no longer in charge? In 1922 Britain had granted independence to Egypt, although, as it turned out, the British remained highly influential in Egypt until 1956. With their newly-gained political independence, perhaps the more zealous Muslim Egyptians would follow the example set by their Turkish co-religionists. Going to London was an excellent way of cementing relationships with the Anglicans, upon whom the Greeks of Egypt might depend for support in some future Egyptian-Greek struggle. Additionally, the Patriarch was impressed by the material support afforded in recent years by the Anglican Church to the suffering Churches of Russia and of Constantinople.

On 21 July, 1925, Patriarch Photios and his entourage finally departed London and travelled to Paris and onwards to Évian-les-Bains in eastern France where the Patriarch underwent a course of medical treatment. Then he attended the Universal Christian Conference on Life and Work in Stockholm. The plan was then to go to Belgrade before returning to Egypt. However, on reaching Zurich on 6 September, Patriarch Photios died. According to Canon Douglas (who provided no evidence for his claim), Patriarch Photios was on his way to visit the Patriarchs of Serbia and Romania to tell them that he, Patriarch Photios, had changed his mind about the Anglicans, and to discuss with the Patriarchs the speedy calling of a Pan-Orthodox Council to discuss union with the Anglican Church. [40] “The Nicaean Commemoration,” The Christian East. September, 1925. vol.6-2. 114.

7. Anglican Generosity

The presence of the large Russian Orthodox delegation at the 1600th Nicaean celebrations in London may be placed in the context of widespread Anglican concern for the plight of the martyred Church within the Soviet Union. From 1919 onwards, the Archbishop of Canterbury had been inundated with a multitude of appeals for material aid, initially coming from clergy within Russia and subsequently from the Russian Orthodox in exile.

In January 1923, Canon Douglas established, under the patronage of the Archbishop of Canterbury, the ‘Appeal for the Russian Clergy,’ tasked with raising and distributing funds. In 1924 the Appeal agreed to fund the establishment of the St Sergius Theological Institute in Paris, under the aegis of Evlogy, Metropolitan of Western Europe, to be directed by Bishop Benjamin of Sebastopol, both of whom attended the 1925 Nicaean celebrations in London.

Some members of the Appeal Committee complained that funds had been given specifically for distribution to clergy in the Soviet Union. However, it was acknowledged that, due to political circumstances, giving relief to clergy and their families within the Soviet Union now was all but impossible. Early in 1926, the name of the fund was changed to ‘Appeal for the Russian Clergy and Church Aid Fund,’ with the stated aims of giving relief to clergy inside and outside of Russia; to the St Sergius Institute in Paris; and to the Russian Orthodox Student Movement in Exile.

The Second World War brought the activities of the Appeal to a halt, by which time, it had raised and distributed £75,000 (today £6 million) – a magnificently generous act of kindness towards the suffering Russian Orthodox Church. [41] For the history of the ‘Appeal for the Russian Clergy and Church Aid Fund’ see D. Davis, “British Aid to Russian Churchmen 1919-1939.” Sobornost,1980. vol. 2. no. 1. 42-56. However, as Donald Davis has noted,

The ‘Appeal for the Russian Clergy’ was mainly a creature of Lambeth and, therefore, dominated by Canon Douglas. Some say that British Christian charity served Lambeth’s desire for Orthodox recognition of Anglican Orders. [42] Davis (British Aid to Russian Churchmen). 55.

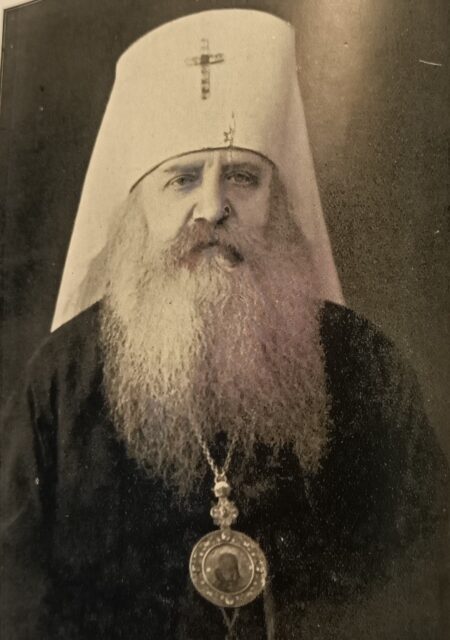

8. Metropolitan Anthony (Khrapovitsky)

Metropolitan Anthony of Kiev, First Hierarch of the Russian Orthodox Church in Exile.

(photo credit: The Christian East, December, 1924)

The Russian delegation was led by Metropolitan Anthony; Metropolitan Evlogy who was based in Paris; and Bishop Benjamin, head of the recently formed Russian Theological Academy in Paris. [43]Metropolitan Anthony (Khrapovitsky) (1863 – 1936) was First Hierarch of the Russian Orthodox Church in Exile (later Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia) from 1919 to 1936. Metropolitan … Continue reading

Accompanying Metropolitan Anthony were his assistant, Archimandrite Theodossy; the Principal Secretary of the Exile Council, Evkustodion I. Makharoblidze; and the former Petrograd Professor of New Testament Exegesis, Dr Nicholas Glubovsky who had become a professor at Sofia University, Bulgaria.

Metropolitan Anthony was well-known for his theologically conservative views. Yet here he was in London, over a period of four weeks, participating liturgically in services held in numerous Anglican Cathedrals and parish churches.

In the past, Metropolitan Anthony had expressed his views on the Roman Catholic Church in vivid terms which made clear his antipathy. In August, 1923, for example, in a speech in Belgrade he said that the Roman Catholics need to abandon “their false dogmas, especially the absurdist one – the Pope’s infallibility in questions of faith.” [44] Letter from G. Bennigsen, Church Times, 30 November,1923. 612. He desired them “to reject all their ‘Roman fairy tales’ about the Apostle Peter as the chief of all the Apostles, as the Popes as successors of the fullness of the imaginary authority of St. Peter, about indulgences, purgatory, etc.” [45] Letter from V. Timotheieff, Church Times, 7 December, 1923. 644. So from this we might gather that the Metropolitan was no liberal He adhered to the doctrine that there is no grace outside the Orthodox Church. For example, in 1916, in reply to an invitation to attend a meeting of the Faith & Order Movement, Archbishop Anthony had written that “all talk about validity [of Protestant orders] is just Talmudic sophistries.” “It makes no difference,” Metropolitan Anthony declared, “whether the non-Orthodox have or have not ‘right beliefs.’ Purity of doctrine would not incorporate them into the Church.” [46] R. Rouse & S.C. Neill (editors), A History of the Ecumenical Movement (SPCK: 1967). 214.

And in a catechism published in Belgrade in 1924, Metropolitan had inserted the following:

Q. Is it possible to admit that a split within in the Church or among the Churches could ever take place?

A. Never. Heretics and schismatics have from time to time fallen away from the One indivisible Church, and, by so doing, they ceased to be members of the Church, but the Church itself can never lose unity according to Christ’s promise. [47] Rouse & Neill (History). 672.

However, by contrast, in 1923, the Metropolitan had envisaged the possibility of the Orthodox Church receiving Anglican clergy in their orders. In an article published in Belgrade, he concluded with these words:

Would it be possible in the event of their reunion with the Church to refuse the Anglican episcopate that which was conceded to the Nestorians and the Donatists by the Council of Carthage and by Basil the Great – that is to say, reception into unity by the Third Rite and with recognition in their existing orders? [48] “The Metropolitan and Anglican Orders.” The Christian East, 12-1924. 55.

Curiously, a year later the Metropolitan did not take this approach, when in August of 1924, he received into the Russian Church a Canadian Anglican deacon, Joseph Côté, as a layman, and then ordained him to the diaconate and priesthood. [49]“The Metropolitan and Anglican Orders.” The Christian East. 12-1924. 54. see also: Anthony (Khrapovitsky), “Why Anglican Clergy Could Be Received in Their Orders,” The Christian East, March, … Continue reading

However, while visiting an Anglican theological college in Canterbury in July, 1925, Metropolitan Anthony expressed the following to the Anglican ordinands:

Look with reverence on your pastoral service as upon the highest service before the Lord, if you will be worthy to fulfill your high responsibility (…) Young people, chosen by God: you are called to the highest earthly service to God — to be the light of the world and the salt of the earth.

These loving words of encouragement to heterodox seminarians illustrate the paradoxical views held by the Metropolitan. Professor Psarev has observed trenchantly,

while [Metropolitan Anthony’s] ecclesiological model of the Church could be fairly represented as a fortress under siege, his personal and spiritual broad-mindedness, his compassion for humankind, so vividly seen in his speech to the Anglican seminarians, did not allow this ecclesiology to result in self-sufficiency and narrow-mindedness. [50]A. Psarev, “The Soul and Heart of a Faithful Englishman is not Limited by Utilitarian Goals and Plans: the Relations of Metropolitan Anthony Khrapovitskii with the Anglican Church.” ‘The Soul … Continue reading

Even before 1925, the Metropolitan had developed a mindset in which he was looking favourably at the Anglican Church and it is not surprising, therefore, that he accepted the invitation from Canon Douglas to participate at the upcoming Nicaean celebrations in London.

However, there were as many as four additional factors which encouraged a positive response from the Metropolitan. First, after the horrors of the First World War there was a genuine and fervent desire amongst most Christians to pursue a path of peace and reconciliation, not least among the Orthodox. To unite in Christian witness with a desire for worldwide peace and harmony was an instinctive impulse felt by all men of goodwill. The establishment of the League of Nations in 1920 presented a challenge to Christian leaders who felt they should match the pursuit of harmony. Metropolitan Germanos (Strenopoulos) authored the “Synodical Encyclical Letter of the Church of Constantinople to the Worldwide Churches of Christ” which was sent to Church leaders worldwide by the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople, dated1 January, 1920. The Encyclical stated that religious leaders should not

continue to fall piteously behind the political authorities, who, truly applying the spirit of the Gospel and of the teaching of Christ, have under happy auspices already set-up the so-called League of Nations in order to defend justice and cultivate charity and agreement between the nations. [51]Germanos (Strenopoulos), “Synodical Encyclical Letter of the Church of Constantinople to the Worldwide Churches of Christ.” Orthodox and Anglican appeals from 1920 remain inspiration for unity | … Continue reading

Second, the exiled Russian clergy naturally felt a huge sense of gratitude to the Anglican Church, not only for its financial support, but also for its active intervention, for example in 1923 when the personal plea of Archbishop Randall Davidson contributed to the release from a Moscow prison of Patriarch Saint Tikhon.

Third, from the end of World War I the Anglo-Catholic party within the Church of England had made sustained efforts to demonstrate to the Orthodox, and to Metropolitan Anthony in particular, that there were no barriers to closer ties between the Orthodox and the Anglicans. Both Bishop Gore and Canon Douglas visited the Metropolitan in Belgrade several times between 1922 and 1925, and it would have been difficult for the Metropolitan to decline their invitation to join in the London Nicaean celebrations, especially as the Anglicans had just agreed to fund the newly-founded St Sergius Theological Institute in Paris. In his letter of invitation Canon Douglas reminded the Metropolitan of this obligation:

We are greatly interested in the success of the new Theological Academy in Paris, and we are absolutely sure that we shall be able to collect a sum of money every year to support it, and you will perfectly understand how important it is for you to come for that reason, [being] so well-known a person as yourself in the sphere of Theological education of all the Russian Orthodox Church. [52] Letter from J. Douglas to Anthony (Khrapovitsky), 15 April, 1925. Douglas 26, f26. LPL.

A fourth factor was that back in April, when the Westminster plans for the Nicaean celebration were being formed, Canon Douglas was convinced that there would not be any senior representation from the Greek Churches, other than Metropolitan Germanos of Thyateira, who lived in London. Canon Douglas added

“… and if you will agree to come [as] the oldest representative of the Russian Church, you will be received here as the First representative of the Greek Orthodox Church.” [53] Letter from J. Douglas to Anthony (Khrapovitsky), 15 April, 1925. Douglas 26, f25. LPL.

This was an allusion to the fact that the exiled Russian bishops in Serbia were concerned because Metropolitan Germanos was beginning to have “pretensions to power over all Orthodox Churches in West and Central Europe.” [54] Geffert (Eastern Orthodox). 93.

The presence of the Russian bishops in London — and of Metropolitan Anthony in particular — would be a vivid encouragement to Metropolitan Germanos to put aside such pretensions.

The four-week stay in England had a profound impact on Metropolitan Anthony. As he travelled back from London to Belgrade, in August the Metropolitan visited Berlin, where he gave an interview to a reporter from the Church Times, re-published verbatim in the American newspaper, The Living Church. Metropolitan Anthony of Kiev summarized his new perspective:

…the dogmatic differences between us and the Anglican Church have been almost finally reconciled… I declared that, from my personal point of view, it appeared to me absolutely legal, in accordance with the first canonical rule of Basil the Great and the ninety-fifth rule of the Sixth Ecumenical Council to admit in the ‘third rank’ – that is to say without fresh, outward ritual of consecration – Anglican clerics and bishops wishing to join the Orthodox Church. [55] “Reunion of Churches Nearer, Opinion of Russian Orthodox Metropolitan,” The Living Church, 29 August,1925. 589.

The Metropolitan acknowledged in the interview that complete union with the whole Anglican Church was improbable; just with “the extreme right wing of the High Church.”

Later in Belgrade in 1925 the Episcopal Council of the Russian Orthodox Church in Exile established a commission to examine rapprochement between the Orthodox and the Anglicans. Chaired by Metropolitan Anthony, the first meeting of the commission took place only in late 1926. The commission produced no tangible results.

9. Recognition of Anglican Orders

The Westminster Abbey celebration of the 1600th anniversary of the First Ecumenical Council was linked inextricably to Anglo-Catholic ambition for having Anglican orders recognised as valid by the Orthodox Church. Led by Canon Douglas and Bishop Gore, it was the highpoint of a sustained campaign to persuade the Orthodox to give their orders the same status as given by mainstream Orthodox to Roman Catholic orders, that is to say, to state that Anglican orders possess Apostolic Succession and, in the case of union with the Orthodox Church, Anglican clergy would be received “in their orders” — without any necessity for ordination.

After the 1896 papal condemnation of Anglican Orders, a section of the Anglo-Catholic wing of the Church of England determinedly pursued a programme which had the explicit aim of gaining from the Orthodox recognition of Anglican Orders as being valid. A major turning point came in 1922 when 3,175 Anglo-Catholic clergy signed an “Appeal to the Orthodox”, a statement of faith which presented the nature of Anglican belief in terms which were aimed at demonstrating that there was nothing in Anglican doctrine and dogma to which the Orthodox could object. This “Appeal” was a disaster because the evangelical wing of the Anglican Church vocally repudiated the “Appeal,” and moderate Anglicans distanced themselves from the “Appeal” precisely because it was so unacceptable to Evangelicals.

However, the “Appeal” did bear some fruit. In July, 1922, Patriarch Meletios IV of Constantinople and his Synod issued a letter which said that the Church of Constantinople recognised Anglican Orders “as those of Roman, Old Catholic and Armenian Churches.” The Patriarch sent the Constantinople declaration to other Orthodox Churches and asked for their opinion. Only two replied positively — Jerusalem and Cyprus. [56] The Romanian Church responded negatively in 1925. Notice that both Churches exist in territory ruled by the British. Both responded cautiously and tentatively, clearing assuming that the new policy would be applied to individual converts and not as a step to intercommunion. The Jerusalem statement affirmed Anglican orders as having the same validity

…which the Orders of the Roman Church have, because there exist all the elements which are considered necessary from an Orthodox point of view for the recognition of the grace of Holy Orders from Apostolic Succession. [57] Letter from Damianos (Kasiotes) to Randall Davidson, 12 March, 1923. Douglas, 35, f36c. LPL.

Archbishop Cyril III (Vassiliou) of Cyprus was quite explicit as to the limits of what was being recognised:

“Inasmuch as clergy entering the bosom of the Orthodox Church from these Churches are received without reordination… the same should hold good in the case of Anglicans.” [58] “Orthodox and Anglican Ordinations.” Church Times,18 May, 1923. 580.

Then in November, 1923, the Church Times related that Canon Douglas had been in Belgrade to discuss the question of Anglican orders with Metropolitan Anthony, who, it was reported, “though a conservative theologian, had been willing to place them on a par with Roman Orders…” [59] “Anglican & Eastern Association: The Seventeenth Anniversary.” Church Times, 16 November,1923. 551.

The Anglo-Catholics were jubilant. They ignored an important fact: the Orthodox, despite having always recognised that the Roman Catholics have apostolic orders, were not in communion with the Roman Catholics — the two Churches had not been in communion for nearly a thousand years. The Anglo-Catholics conveniently ignored the historical reality and started to talk openly about the Orthodox having recognised Anglican Orders. For example, at a 1925 meeting of the Anglican & Eastern Churches Association, the Anglican Bishop of Winchester triumphantly affirmed that “the recognition of our Orders [by the Orthodox] shows what a long step we have made upon the long road towards mutual understanding.” [60] “The Bishop of Winchester Reports Progress.” Church Times, 20 November,1925. 593.

And when, in July,1925, at the Holborn Restaurant Banquet (see Section 4 above), Metropolitan Anthony repeated his view that individual members of the Anglican clergy, who wished to become Orthodox, might be received “in their orders”, his comments were met with thunderous applause from the hundreds of clerics assembled there.

10. Conclusion

What can we learn from the unique and historic events of the 1925 Nicaean celebrations in London? I suggest that there might be three salutary lessons to be learned.

Do not trust in rulers and in the sons of men (Psalm 145:3)

We can now understand why the two Patriarchs made their historic journey to London and, to the surprise of everybody, entered into joint prayer with the Anglicans, not just at one service but repeatedly over a period of a month. The Patriarchs imagined that the hierarchs of the Church of England, being an established Church, possessed influence with the UK government which was the occupying colonial power in both Palestine and Egypt. If only the Patriarchs could plead their case face to face with the most senior Crown Minister for the Colonies, and even with King George V, then perhaps the shackles imposed by Sir Anton Betram in Jerusalem might be removed. Of course, they were wrong. The political influence of the Church of England in these matters was largely illusory. Indeed, the Oxford Professor of Divinity, Canon H. L. Gould was sensitive to the prevalent belief among Eastern Orthodox clergy about the supposed political influence of the Church of England. In a sermon of November, 1925, addressing a meeting of the A&ECA, he warned the Anglo-Catholics,

Do not for a moment let us encourage our brothers in the East to suppose that intercommunion with us will mean their protection by the British Army and the British Fleet. It will mean nothing of the kind. Let us tell them the truth. Real Churchmen are but a small minority of the English people. They have never in the past shaped national policy, nor are they likely to do so in the future. The confusion of politics with religion, and especially of nationalism with religion, has been ruinous in the East as with ourselves. [61] “East and West: A Sermon Preached by H. L. Goudge.” The Christian East. 12,1925. 205.

And, indeed, despite the pleas of the Patriarchs, nothing changed: Sir Anton Betram continued to investigate and, with the publication of not one but two damning reports, publicly humiliating Patriarch Damianos; this was followed by the enforced sale of numerous Patriarchal properties, many to Jewish Zionists.

The rich will rule over the poor, and servants will lend to their own masters (Proverbs 22:6)

The enthusiastic participation of the Russian Metropolitans in the ecumenical events surrounding the 1925 Nicaean celebrations hosted by the Anglicans can be understood partly in the context of the generosity of the Anglicans: the Church of England was hugely generous in its financial support of the exiled Russian clergy. If nothing else, plain good manners demanded the attendance of the exiled Russian bishops in London in June, 1925, although their entering into joint prayer with the Anglicans is less easy to understand, other than, perhaps, a singular application of economia to deal with unique circumstances.

The wisdom of astute men will know their ways, but the folly of men without discernment is in their deceit (Proverbs 14:8)

Led by Bishop Gore and Canon Douglas, the Anglo-Catholics misrepresented the three Orthodox statements (Constantinople, Jerusalem, Cyprus) about the validity of Anglican orders. It is quite clear that these statements refer to situations where individual Anglican clergymen wish to become Orthodox. The statements confirm that it would be possible to receive individual Anglican clergymen in their orders as a concession, as an act of οικονόμια (economia). [62]In the application of canons in the life of the Orthodox Church there are two related concepts: strictness and economy. Strictness (akrivia) emphasises strict adherence, precision and exactness. … Continue reading From an Orthodox point of view, such a concession in no way could be understood as a general recognition of the validity of Anglican orders. From 1923 onwards, Anglo-Catholic Anglicans promoted the line that their orders had been recognized by all the Orthodox, conveniently forgetting or ignoring the import of those Orthodox statements — that they were specific, not general. Furthermore, the Anglicans began to say that their orders had been recognised by all the autocephalous Churches, although by June, 1925 only three of the ten had made any sort of pronouncement.

Predictably, the outcome was failure. After 1925, Orthodox and Anglicans remained as far apart theologically as they had always been. The driving force underpinning the 1925 Nicaean celebrations, the rather deceptive quest for recognition by the Orthodox of the validity of Anglicans orders, was not a step towards unity. General recognition can only be an outcome of theological agreement; recognition cannot precede theological agreement. Endless hours of discussion, and so many fine words that have poured forth from both sides over the last one hundred years, yet theological agreement remains elusive.

When a foreigner resides among you in your land, do not mistreat them. The foreigner residing among you must be treated as your native-born. Love them as yourself, for you were foreigners in Egypt (Leviticus 19:33-34)

The only tangible legacy of the 1925 Nicaean celebrations is a dining club. It will be remembered that Canon Douglas set up a committee to organize the month-long programme of church services, cultural visits, garden parties and civic ceremonies for the visiting Orthodox hierarchs. [63] Christian East. 01.1926. 225. Athelstan Riley. Chronicle and Causerie. This committee became the Nikaean Club, [64] The Nikaean Club accessed February, 2025. which even today has the task of hosting receptions and dinners for representatives of non-Anglican churches making official visits to the Archbishop of Canterbury — the only lasting legacy of the 1925 celebrations in London of the 1600th anniversary of the First Ecumenical Council of Nicaea.

References

| ↵1 | A detailed examination of how politics has influenced Anglican-Orthodox relations is to be found at Bryn Geffert, Eastern Orthodox and Anglicans (University of Notre Dame, 2020). |

|---|---|

| ↵2 | “The Council of Nicaea. Sixteenth Centenary Celebrated in Westminster Abbey,” Onward. 11 July, 1925, 207. |

| ↵3 | “Eastern Prelates in England.” Church Times. 26 June, 1025. 781. |

| ↵4 | including Prof. H. Alivizatos (Church of Greece); Archpriest Radu (Romanian Patriarchate); Principal Secretary of the Russian Exile Council, Evkustodion I. Makharoblidze, and Professor of New Testament Exegesis, Dr Nicholas Glubovsky who had become a professor at Sofia University, Bulgaria; together with the London-based Russian and Greek clergy. |

| ↵5 | .D., “The Patriarchs at the Abbey,” Church Times, 3 July,1925. 25. |

| ↵6 | “The Late Patriarch of Alexandria,” Church Times, 13 November,1925. 574. |

| ↵7 | John Greig, Report to the Archbishop of Canterbury’s Eastern Churches Committee, 1924. Bell 198, ff. 94-96, Lambeth Palace Library (LPL). |

| ↵8 | cited by J. A. D., “The Visit of the Patriarchs,” Church Times, 24 July, 1925. 103. |

| ↵9 | Canon John Albert Douglas (1868 – 1956) John and Charles Douglas accessed January, 2025. |

| ↵10 | The Eastern Church Association was founded in 1864. In 1914, it adopted the name A&ECA when it merged with the Anglican and Eastern Orthodox Churches Union, a merger that was arranged between the Reverend H. J. Fynes-Clinton and Canon J. A. Douglas. |

| ↵11 | However, see Y. R. Kim (ed.), Cambridge Companion to the Council of Nicaea (Cambridge University Press, 2021). 96. Here 20 May is suggested, following the 5th century historian, Socrates of Constantinople. |

| ↵12 | J. A. Douglas, letter to Anthony (Khrapovitsky), April, 1925. Douglas 26, f25. LPL. |

| ↵13 | “Eastern Prelates in England,” Church Times, 26 June,1925. 781. |

| ↵14 | “It was noteworthy that here [at Clewer] as elsewhere the Patriarchs and other bishops rendered adoration to the Blessed Sacrament in the manner customary in their own Church i.e. with profound obeisance and touching the ground with the right hand.” “The Patriarchs in England,” Church Times, 10 July,1925. 55. |

| ↵15 | J. A. D., “The Visit of the Patriarchs,” Church Times, 24 July,1925.103. |

| ↵16 | “The Patriarchs in England.” Church Times, 10 July,1925. 55. |

| ↵17 | Sir Samuel Hoare (1880-1959) from 1916 to 1917 was head of the British Intelligence Mission to the Russian General Staff. In that post, he reported the death of Rasputin to the British government. |

| ↵18 | C. J. Birchall, Embassy, Emigrants, and Englishmen (Holy Trinity Publications, 2014). 236. For further consideration of the views of Metropolitan Anthony: see section 8 below. |

| ↵19 | Letter from W. Williams to A. Riley, 30 May, 1925. Douglas 26, f264. LPL. |

| ↵20 | Birchall (Embassy). 237. |

| ↵21 | Fr Vladimir had been elevated to the rank of Archpriest by Metropolitan Evlogy on the previous Sunday. |

| ↵22 | Benediction is a Latin rite in which Jesus Christ is said to be adored in the consecrated Host exposed on the altar. |

| ↵23 | Letter from V. Timotheieff to J. Douglas. Douglas 26, f201. LPL. |

| ↵24 | Anglo-Catholics emphasize the Catholic rather than the Protestant heritage of the Anglican Church. Anglo-Catholics are sometimes called “high” church people, in that they give a “high” place to the importance of the episcopal form of church government, the sacraments, and liturgical worship. Anglican Evangelicals stress the Protestant heritage of Anglicanism. |

| ↵25 | Letter from J. Douglas to C. Gore. Douglas 26, ff.202. LPL. |

| ↵26 | Damianos I (1848 – 1931) was Greek Orthodox Patriarch of Jerusalem from 1897 to 1931. Archbishop Timotheos (1878 – 1955) was Greek Orthodox Patriarch of Jerusalem from 1935 to 1955. |

| ↵27 | Letter from J. Douglas to H. Luke, 19 June, 1925. Douglas 26, f80. LPL. |

| ↵28 | Letter from J. Douglas to S. Gaselee, 19 June, 1925. Douglas 26 f86. LPL. |

| ↵29 | The Mandate for Palestine was a League of Nations mandate for British administration of Palestine and Transjordan. Britain administered Palestine from 1920 to 1948. |

| ↵30 | for a detailed account, see K. Papastathis, “Diplomacy, Communal Politics, and Religious Property Management: The Case of the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem in the Early Mandate Period.” Chapter 11. Ordinary Jerusalem, 1840-1940.ebook edited by A. Dalachanēs, & V. Lemire (Brill, 2018). |

| ↵31 | A. Bertram, & H. C. Luke, Report of the Commission Appointed by the Government of Palestine to Inquire into the Affairs of the Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem (Oxford University Press,1921). |

| ↵32 | C. Gore, “Memorandum for the Eastern Churches Committee.” MS2627, ff112-115. LPL. |

| ↵33 | A. Bertram & J. W. A. Young, Report of the Commission Appointed by the Government of Palestine to Inquire and Report Upon Certain Controversies Between the Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem and the Arab Orthodox Community (Oxford University Press,1926). |

| ↵34 | Letter from A. Edgcumbe to J. Douglas, 11 July, 1925. Douglas 26, f249. LPL. |

| ↵35 | “and of All Africa” was added to the Alexandrian title after 1927. |

| ↵36 | J. A. D., “Death of Photios Patriarch and Pope of Alexandria.” Church Times, 11.9.1925. 283. |

| ↵37 | Letter from J. Douglas to C. Gore. Douglas 26, f202. LPL. The exact quotation reads, “We have two of the most stubborn conservatives here in Photios and Anthony, and Glubovsky is not a liberal!” |

| ↵38 | “The Late Patriarch of Alexandria.” Church Times, 13 November, 1925. 574. |

| ↵39 | Anson, P. Bishops At Large. (Faber, 1964) 185-187; “Bishop Mathew and the Orthodox”, The Glastonbury Bulletin, 64. May, 1982. 197-206. |

| ↵40 | “The Nicaean Commemoration,” The Christian East. September, 1925. vol.6-2. 114. |

| ↵41 | For the history of the ‘Appeal for the Russian Clergy and Church Aid Fund’ see D. Davis, “British Aid to Russian Churchmen 1919-1939.” Sobornost,1980. vol. 2. no. 1. 42-56. |

| ↵42 | Davis (British Aid to Russian Churchmen). 55. |

| ↵43 | Metropolitan Anthony (Khrapovitsky) (1863 – 1936) was First Hierarch of the Russian Orthodox Church in Exile (later Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia) from 1919 to 1936. Metropolitan Evlogy (Georgievsky) (1868 – 1946) was Administrator of the Russian parishes in Western Europe, 1921-1946. Benjamin (Fedchenko) (1880-1961) Bishop of Sebastopol, later Metropolitan Benjamin of Saratov and Volsky. In 1927, he left the St Sergius Institute, Paris, and relocated to Serbia. |

| ↵44 | Letter from G. Bennigsen, Church Times, 30 November,1923. 612. |

| ↵45 | Letter from V. Timotheieff, Church Times, 7 December, 1923. 644. |

| ↵46 | R. Rouse & S.C. Neill (editors), A History of the Ecumenical Movement (SPCK: 1967). 214. |

| ↵47 | Rouse & Neill (History). 672. |

| ↵48 | “The Metropolitan and Anglican Orders.” The Christian East, 12-1924. 55. |

| ↵49 | “The Metropolitan and Anglican Orders.” The Christian East. 12-1924. 54. see also: Anthony (Khrapovitsky), “Why Anglican Clergy Could Be Received in Their Orders,” The Christian East, March, 1927, VIII-1.60-69. |

| ↵50 | A. Psarev, “The Soul and Heart of a Faithful Englishman is not Limited by Utilitarian Goals and Plans: the Relations of Metropolitan Anthony Khrapovitskii with the Anglican Church.” ‘The Soul and Heart of A Faithful Englishman is not Limited by Utilitarian Goals and Plans’: the Relations of Metropolitan Anthony Khrapovitskii with the Anglican Church – ROCOR Studies Historical Studies of the Russian Church Abroad. accessed February, 2025. |

| ↵51 | Germanos (Strenopoulos), “Synodical Encyclical Letter of the Church of Constantinople to the Worldwide Churches of Christ.” Orthodox and Anglican appeals from 1920 remain inspiration for unity | World Council of Churches accessed December, 2024. |

| ↵52 | Letter from J. Douglas to Anthony (Khrapovitsky), 15 April, 1925. Douglas 26, f26. LPL. |

| ↵53 | Letter from J. Douglas to Anthony (Khrapovitsky), 15 April, 1925. Douglas 26, f25. LPL. |

| ↵54 | Geffert (Eastern Orthodox). 93. |

| ↵55 | “Reunion of Churches Nearer, Opinion of Russian Orthodox Metropolitan,” The Living Church, 29 August,1925. 589. |

| ↵56 | The Romanian Church responded negatively in 1925. |

| ↵57 | Letter from Damianos (Kasiotes) to Randall Davidson, 12 March, 1923. Douglas, 35, f36c. LPL. |

| ↵58 | “Orthodox and Anglican Ordinations.” Church Times,18 May, 1923. 580. |

| ↵59 | “Anglican & Eastern Association: The Seventeenth Anniversary.” Church Times, 16 November,1923. 551. |

| ↵60 | “The Bishop of Winchester Reports Progress.” Church Times, 20 November,1925. 593. |

| ↵61 | “East and West: A Sermon Preached by H. L. Goudge.” The Christian East. 12,1925. 205. |

| ↵62 | In the application of canons in the life of the Orthodox Church there are two related concepts: strictness and economy. Strictness (akrivia) emphasises strict adherence, precision and exactness. Economia (oikonomia) indicates a more flexible application of the canons. |

| ↵63 | Christian East. 01.1926. 225. Athelstan Riley. Chronicle and Causerie. |

| ↵64 | The Nikaean Club accessed February, 2025. |

This is a thoughtfully reasoned and well researched article. I had read quotes of Metropolitan Anthony concerning reception of Anglican clergy but i had not previously understood the context in which those statements were made or what came before and after.

I appreciate the article especially because it recounts the activities of the patriarchs before their attendance at the Stockholm meeting in 1925. The ecumenical relationships that were established that summer were significant for future claims by other Protestant churches that held on to a liturgical tradition.