In the 1930’s, both the Serbian Orthodox Church and the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia (ROCOR) displayed intense interest in the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church, otherwise known as the Indian Orthodox Church. [1]In the 1930’s, what we now call The Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia was known in the UK variously as The Russian Orthodox Church in Exile or the Karlovtsi Synod. Throughout this essay I … Continue reading In this paper I highlight the key personalities of this venture to understand how these events unfolded between 1930 and 1940. Before doing that, it might be helpful to understand what we mean when speaking of the “Indian Orthodox Church.”

Oriental Christians

This term generally refers to the Churches which became separated from the Byzantine Orthodox Church (or “Eastern Orthodox Church”) after the Council of Chalcedon which was held in AD 451. This Council, which the Byzantine Orthodox know as the Fourth Ecumenical Council, was concerned with defining what we mean when we say that Christ is both truly Human and truly Divine. While all the local churches within the Byzantine Empire accepted the definitions of Chalcedon, almost all the local Churches outside the Byzantine Empire, especially in Syria and Egypt, did not accede to Chalcedon. As Metropolitan Kallistos succinctly characterized this division, “[a]s so often, theological differences were made more bitter by cultural and national tension.”[2] T. Ware, The Orthodox Church. (London: Penguin Books. 1963). repr. 1997. 29. Today there are more than 70 million Oriental Christians who belong to six autocephalous Churches: the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria, the Syriac Orthodox Church of Antioch, the Armenian Apostolic Church, the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church, the Eritrean Orthodox Tewahedo Church, and the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church.

The Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church

The highest concentration of Christians in India is found in Kerala, south-west India, where 20% of the population — some 6 million people — follow Christianity. Almost all belong to communities which trace their origins to St Thomas the Apostle who, in AD 52, brought the Gospel to India, having arrived in what is now the modern state of Kerala. Often these Christians are referred to as “Saint Thomas Christians.” Today there are eight distinct Churches in Kerala which trace their origins to Saint Thomas: three are Reformed Churches; two are a part of the Roman Catholic Church; one belongs to the Assyrian Church of the East; and two are non-Chalcedonian Orthodox (Oriental Christians) — the Jacobite Christian Church and the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church.[3] The division between the two non-Chalcedonian Orthodox (Oriental Christians) in India occurred in1912. It is the latter, also known as the Indian Orthodox Church, with about 400,000 adherents, that was the focus of interest for the Russian Orthodox.

A visitor to the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church, the Anglican Bishop Noel Hall, in 1937 wrote enthusiastically about his experience of worshipping with the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Christians:

“After assisting [sic] at the venerable liturgy of St James at Tiruvella on my first Sunday Travancore, even deeper and more predominant than the thrill of being amidst an Indian people who ancestors had been Christians when my own were heathen, was the sense that I had been worshipping in all essentials as the primitive Church had worshipped. Some of the ceremonial, no doubt, was peculiarly Indian, especially the more audible accompaniments of the great moments of the liturgy — the ringing of bells and the rattle of disc-shaped fans: some features of the liturgy, notably the insertion of the words “Who was crucified for us” in the trisagion, recalled the controversies following the Council of Chalcedon which ended in the assertion of Syrian independence of the great Church of Byzantium. But these things are subordinate and accidental: the main tradition derives unaltered from the primitive Church: the Holy Kurbana [4] Divine Liturgy is the Church’s proclamation of her faith in the mystery of Redemption, and in this proclamation the whole body of the faithful take their part. The more solemn parts of the liturgy are still recited in sonorous Syriac,[5] The liturgical language of the Thomas Christians is Syriac, a dialect of Aramaic spoken by the Saviour. which is not understood by the people, but this in no way hinders either their devotion or their attention, as, guided by a deacon, they share in one of the most sublime prayers of Christendom.”[6] N. Hall, “A Visit to the Syrian Christians of Travancore.” The Christian East, 1937. XVII. 1 & 2. 43.

Oriental Christians and the Russian Church

The first recorded contact between the Indian Church and the Russian Church occurred in 1851 when Syrian Christians from both India and Mesopotamia (Iraq) approached the Russian Consul in Constantinople with a proposal to consider union between the Syrian Orthodox and the Russian Orthodox. Perhaps the ensuing Russo-Turkish War made it impossible for those conversations to proceed. In 1898, a bishop of the Syrian Christians in India petitioned the Russian Most Holy Governing Synod to consider reunion but the matter remained unresolved.[7] S. N. Bolshakoff. “The Syrian Church.” The Eastern Churches Broadsheet. September, 1948. 2-4. In 1903 Russian Orthodox missionary work was described in a book by Archpriest Eugene Smirnoff, Chaplain to the Imperial Embassy in London (d. 1923).[8] E. Smirnoff, A Short Account of The Historical Development and Present Position of Russian Orthodox Missions (1903. London: Rivingtons). He makes no mention of a Mission addressed to the Oriental Churches. Interestingly, only a year later, in 1904 Fr Eugene was approached in London by a member of the Syrian Orthodox Church in India, requesting that the Russians send a bishop or priest to the Indian Orthodox with a view to uniting to the two communities. Fr Eugene informed Metropolitan Anthony Vadkovsky of St Petersburg (d. 1912) of this request. The Metropolitan replied that it was not possible to send a bishop or priest to India at this time.[9] See C. J. Birchall. Embassy, Emigrants, and Englishmen: The Three Hundred Year History of a Russian Orthodox Church in London. (Jordanville, New York: Holy Trinity Publications, 2014). 170.

Serge N. Bolshakoff (d. 1990), in his 1943 book, The Foreign Missions of The Russian Orthodox Church, chronicles the conversion to Russian Orthodoxy by thousands of Nestorians of the Assyrian Church of the East which occurred in the decade preceding the First World War.[10] S. N. Bolshakoff, The Foreign Missions of The Russian Orthodox Church. (1943. London: SPCK.) In this case, the members of the ancient Church converted to Eastern Orthodoxy; they did not simply restore communion. In 1956, the well-known ecumenist, Nicolas Zernov (d. 1980), published his book, The Christian East: The Eastern Orthodox Church and Indian Christianity, which is a comparative study of the faith and practice of the Eastern Orthodox Church and the Indian Orthodox Church. Despite its thoroughness, the book fails to mention any historical contacts between the two Churches.[11] N. Zernov, The Christian East: The Eastern Orthodox Church and Indian Christianity. (Delhi: SPCK, 1956).

Archimandrite Andronik Elpedinsky

Central to the story of interaction between the Russian Church and the Indian Orthodox Church in the 1930’s is the remarkable figure of Archimandrite Andronik, in the world Andrei Elpedinsky. Born in 1894, before the First World War Elpedinsky had been a seminarian in Karelia in north west Russia. After the chaos of the First World War, Revolution and Civil War, Elpedinsky had become a volunteer with the White Army, eventually going into exile and finding his way to Finland, Germany and then, in 1923, to France. By 1925, he had enrolled in the very first class of the newly-founded Saint Serge Theological Institute in Paris. In the same year, he became a monk, taking the name Andronik, and was subsequently ordained by Metropolitan Evlogii Georgievskii (d. 1946). Fr Andronik became a parish priest in Belfort, north east France until 1931, when, with the blessing of Metropolitan Evlogii, he left Europe and travelled first to Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) and then to Bangalore in the south of India.[12] A. Stanway, “Perpetual Embers: A Chronicle of ROCOR’s Missionary Efforts in India.”15.https://www.academia.edu/38192487/Perpetual_Embers_A_Chronicle_of_ROCOR_s_Missionary_Efforts_in_India

Fr Andronik had conceived of the idea of becoming a monk-missionary in India while he was still in Russia. He had prepared for the venture by working in a car factory in France and saving all his earnings so that he could afford to build a small church at his final destination which proved to be Kerala. In Kerala, Fr Andronik became acquainted with the head of the Church of the Malankara Orthodox Christians, His Holiness Baselios Geevarghese II, Catholicos of the East and Malankara Metropolitan (d. 1964). He decided that his mission was not to convert Hindus to Christianity but to mediate the return of the Indian Orthodox to the Eastern Orthodox Church. Fr Andronik moved from Bangalore and went to live among the Indian Orthodox Christians, initially at Bethany Ashram in Vadaserikara, a village near Travancore, where he remained for about a year. Then Fr Andronik became acquainted with the Indian Orthodox Mount Tabor Ashram (a monastery that had been founded in 1929) in Pathanpuram. In 1933, the fathers of the Ashram allocated to Fr Andronik an eight-acre plot on the peak of a mountain at nearby Pattazhy. First Fr Andronik had to clear the tropical brushwood and the wild animals which lived there. Writing in Журнал Московской Патриархии, A. E. Buevsky creates a vivid image of the ascetic Fr Andronik:

“On this ‘Mount Tabor,’ as Fr Andronik had named it, he erected a modest church and residential buildings; he also developed a modest garden with fruit trees… By virtue of his example of authentic Christian monastic life, indefatigable labours, tact, and inner charm, Fr Andronik acquired love and respect not only from Christians, but also from pagans, kneeling down before him and seeking his blessing, or inviting him in the capacity of a judge in arbitrating between the Christians and the pagans.”[13] A. S. Buevsky, “The Legacy of the Apostle Thomas (in Russian).” Журнал Московской Патриархии, 51-62.

For a time, Fr Andronik shared his living quarters with the future Archimandrite Lazarus Moore (d. 1992) who, while still an Anglican priest, stayed there for about a year in 1934. It was that experience that led Fr Lazarus to become Orthodox. During his time in Kerala, Fr Andronik spent much time in developing relations with the people and the clergy of the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church, with the hope that it would eventually enter into communion with the Eastern Orthodox Church.

Buevsky confirms that Fr Andronik’s approach was not to convert the Saint Thomas Christians but, rather, to restore communion between the Indian Orthodox Church and the Eastern Orthodox Church.[14] Buevsky, “The Legacy of the Apostle Thomas,” 51-62. He wanted the Indian Orthodox to become acquainted with the life and practice of the Russian Orthodox Church and he did this by daily offering the Divine Services in his own small chapel and by preaching in churches of the Indian Orthodox. Fr Angelos Stanway writes that it was at this time Fr Andronik “received an ukaz from Paris, stating that he had been appointed the Russian priest for the whole of India, and therefore pastor to the entire Russian diaspora on the subcontinent.”[15] Stanway. “Perpetual Embers.” 25. As such, Fr Andronik travelled widely in India. For example, in 1937, The Times of India carried advertisements for “The Holy Mass” which was to be celebrated by Fr Andronik at an ancient church in Bombay (now Mumbai) at St Peter’s Armenian Church, which, despite the name, belongs to the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Christians. “Members of all Orthodox Churches are cordially invited to attend.”[16] The Times of India. 12.02.1937. 3. The journey from Kerala to Mumbai and back to Kerala is more than 1,600 miles!

In the Serbian archives, Fr Andronik is referred to as “the Russian mission among the Indians.”[17] “Eighty Years of Indo–Serbian Orthodox Relations & Saint Dositej Vasić of Zagreb.”http://www.spc.rs/eng/eighty_years_indoserbian_orthodox_relations_saint_dositej_vasic_zagreb (March 2019). In January, 1937, the Serbian bishop, Metropolitan Dositheus, (of whom more later) visited the Monastery of the Transfiguration. From there he visited Fr Andronik at Pattazhy and took the opportunity to elevate Fr Andronik to the rank of archimandrite, at the request of Metropolitan Evlogii in Paris. In 1949, Archimandrite Andronik left India and went to North America, eventually becoming abbot of Saint Tikhon’s Monastery in Pennsylvania where he passed away in 1958. He gave an account of his work in India in a book, written in Russian, entitled Eighteen Years in India, and published posthumously.[18] Andronik Elpedinskii, Eighteen Years in India; repr. 2012. Восемнадцать лет в Индии. Moscow: Сретенский монастырь.

Moves towards Unification

For all the 18 years in which Fr Andronik laboured in India, the first hierarch of the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church was His Holiness Baselios Geevarghese II, Catholicos of the East and Malankara Metropolitan (d. 1964). Mar Geevarghese II was born in Kottayam. In 1898 he was ordained as priest. He then took charge of the southern dioceses of the Indian Orthodox Church. In 1912, Abded Messiah (d. 1915) consecrated him at Parmula Seminary as Metropolitan Geevarghese Mar Gregorios, becoming the Metropolitan of Thumpamon, Kollam and Niranam dioceses. In 1929, the Episcopal Synod of Malankara installed him as Catholicos of the East, succeeding Mar Geevarghese I, who had died in the previous year. When the Malankara Association met in 1934 at the Seminary in Kottayam, he was chosen as Malankara Metropolitan. Apart from consecrating twelve metropolitans, and ordaining more than a thousand priests and deacons, he founded and consecrated many churches. Mar Geevarghese II died in 1964; the Indian Orthodox Church observes his memory on 3 January.[19] “Baselios Geevarghese II.”https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baselios_Geevarghese_II

Fr Andronik could only pursue his missionary work with the blessing of Mar Geevarghese II and it is clear that Fr Andronik would have had many opportunities to inform him and his fellow clergy about the Russian Orthodox Church. In 1934, Mar Geevarghese II went to Antioch in order to meet with bishops of the Syriac Orthodox Church. On his way back to India, Mar Geevarghese II visited the Greek Patriarchate of Jerusalem where Archbishop Anastassy Gribanovsky (d. 1965) was Head of the Russian Ecclesiastical Mission (ROCOR).[20] Buevsky, “The Legacy of the Apostle Thomas,” 51-62. Indeed, Mar Geevarghese II stayed at the large Russian Orthodox Convent of the Ascension on the Mount of Olives.[21] Buevsky. “The Legacy of the Apostle Thomas.” 51-62. According to Fr Angelos, when Mar Geevarghese II met with Archbishop Anastassy, he “requested that the Russian Church send missionaries [sic] to India.”[22] “Perpetual Embers.” 8. Following this visit to Jerusalem, it appears that Mar Geevarghese II decided to enter into formal discussions about the unification of the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Christians with the Russian Orthodox Church, as represented by the ROCOR. In October, 1935 Archbishop Anastassy was able to report to the Council of Bishops, meeting in Sremski-Karlovci, that he was convinced that the Indian Orthodox were intent on unification with the Russian Orthodox. The Indian Orthodox had told him that they did not acknowledge the authority of the Council of Chalcedon simply because they did not participate in that Council; they were not present. Archbishop Anastassy had requested the Indian Orthodox to present an account of their faith in writing.

In a letter of 29th May, 1935, Mar Severios of India had written to Archbishop Anastassy to confirm their intent on unification talks.[23]“Посещение Южной Индии епископом Димитрием.” Церковная жизнь. 1936: 4-5. 73. cited by A. V. Psarev in The Attitude of The Russian Orthodox … Continue reading In a separate document, the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church set out their confession of faith. Unfortunately, it was an unofficial and unsigned document.[24] Psarev. The Attitude. 369. They denied that they were Monophysites, affirming that, indeed, Christ has two natures. However, in the confession of faith, they only mentioned the first three Ecumenical Councils. Nevertheless, in consultation with the Serbian Orthodox Church, the decision was made that the ROCOR should continue interaction with the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church, with the Serbians providing material support.[25] Gosudarstvennyi Arkhiv Rossiiskoi Federatsii [GARF] f. 6343, op. 1, d. 257. cited by Psarev, The Attitude, 370. In November, 1935, Archbishop Anastassy, newly elevated to the rank of Metropolitan, wrote to Mar Geevarghese II (in English):

“The Council has studied with much consideration the letter I received from you and the informal declaration of faith which you sent me. The Council found that the declaration continued the same doctrine as is professed by our Holy Orthodox Church for several ages since the times of the Saint Apostles to the present day. Therefore, the Holy Council decided that such a declaration, if forwarded officially and signed by your Holiness and the right Rev. Bishops of your Church, can serve as a foundation for further correspondence. We will be glad and grateful if you will find it possible to send us more detailed declaration. It is of particular importance that it contains a more clear outline of the teaching of your Church with regard to the Ecumenical Councils (…) Acceptance of the Faith, as defined by those Councils is indispensable for anyone desirous to join the Holy Orthodox Church and to belong there to (…) I am glad to add that it was with much sympathy and with a great interest that His Holiness Patriarch Barnabas learned of your desire to join our Church. If needed His Holiness is prepared to give us his assistance and together with us He prays to God to so direct all as to soon unite us in one Faith and intercommunion in Jesus Christ (…)With profound respect and love in Christ I am your Holiness’ obedient servant, Metrop. Anastassy.”[26] GARF, f. 6343, op.1, d.257. cited by Psarev, The Attitude, 371.

Bishop Dimitry Voznesenky of Chailar (d. 1947) was a vicar bishop for the ROCOR diocese of Harbin, Manchuria. Bishop Dimitry had been attending the 1935 meeting of the Council of Bishops in Serbia and, on his way back to Manchuria, on the instruction of the Council of Bishops of the ROCOR, he visited first Colombo, the capital of Ceylon (Sri Lanka) and then south India. Fr Angelos notes that the “Serbian Orthodox Church financed the bishop’s journey to the sum of twenty thousand dinars and agreed to provide further support to ROCOR if the visitation proved fruitful.”[27] Stanway. “Perpetual Embers.” 9. There, with Fr Andronik as his guide and translator, in February, 1936 Bishop Dimitry visited Mar Geevarghese II and the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church for three weeks, holding talks in order to exchange information about the faith and practice of their respective Churches. Fr Andronik wrote:

“A meeting was organized in the residence of the Catholicos with the bishops about the unity of churches. In doctrine — in questions of heresy, especially about Monophysitism — there seemed to be no disagreement in way of unity. More difficult was the question of the Ecumenical Councils. The Christians of South India recognize only three Ecumenical Councils, expressing enmity towards the Fourth Council of Chalcedon. The question was posed as such: If there is no difference in doctrine, the question of the Councils is not so essential.”[28] Elpedinsky, Eighteen Years in India, 166.

Fr Angelos records that Bishop Dmitri, who was very supportive of Fr Andronik, gave him a large sum of money – hidden inside a book by the First Hierarch of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia, Metropolitan Anthony Khrapovitsky (d. 1936).[29] Elpedinsky, Eighteen Years in India, 166. Thereafter, Bishop Dimitry submitted a detailed report to the Synod of Bishops about the Indian Orthodox. He wrote that “the Indian Orthodox did not deny the authority of the last four Ecumenical Councils, but they do not know their dogmatic and canonical formulations and they had asked Bishop Dimitry to send the Indian bishops those resolutions for study.”[30] Psarev, The Attitude, 371.

On his return journey to Harbin, Bishop Dmitri’s ship called in at Singapore, where by chance the English convert, Archimandrite Nicholas Gibbes (d. 1961), was travelling in the opposite direction – from Harbin to Jerusalem and then onward to London. Fr Nicholas recalls their meeting in a letter to his godmother:

“We have enjoyed two days ashore at Singapore and Colombo. At the former of these I had the pleasure of meeting Bishop Demetry (Hailar), who was returning home. … I was therefore glad to hear from his own lips an account of his mission to the Travancore Indian Christians who are known (I believe) as the Syrian Christians. The result was perhaps a little disappointing, as actually no definite agreement was reached. The preliminary work previous to the Bishop’s visit became itself of that nature. The Bishop was greatly hampered by having no knowledge of any language except Russian, which was only understood by one priest, who translated it into English. Then another Indian priest translated the English into their own language. Not an ideal arrangement.”[31] Letter dated 31st March, 1936.Gibbes, N. Unpublished letter, dated 31.3.1936: St. Nicholas Parish Archive, Oxford.

Following the visit of Bishop Dimitry, in July, 1936, Mar Geevarghese II wrote to the Russian bishops:

“I am extremely glad to note that the Council of the Russian Bishops has given special attention to study the doctrines and practices of the Syrian Orthodox Church in Malabar (…) Our people have had the opportunity to study more of the Russian Church and of its faith from Father Andronic who has been residing in our midst for the last few years. From the various talks and speeches he had given at different groups and conventions of our Church, we have been able to learn that the Russian Church keeps a faith closely akin to ours. It was a great privilege and a real joy to me to have entertained a distinguished guest like Bishop Dimitry on his way to China and to learn more authoritatively from him of the Russian faith and practices (…) Regarding the Councils, the Syrian Church holds that the first three Councils are sufficient to declare the true catholicity and teachings of the Apostolic Church established by our beloved Lord; but at the same time, for accommodation, the Church, I suppose does not object to respecting the later Councils in so far as they do not interfere with the decisions of the first Three.”[32] GARF, f. 6343, op.1, d.258. cited by Psarev. The Attitude, 372.

Priest-monks of Metropolitan Nestor: Nathanael (Lvov,) left and Philaret (Voznesensky). Harbin, 1930s

In September, 1936, the Synod of Bishops “resolved to send to the Malabars materials which were necessary for their introduction to Orthodoxy” and they assigned Igoumen Philaret Voznesenky, the son of Bishop Dimitry and future First Hierarch of the ROCOR (d. 1985), to start the mission in India.[33] Psarev. The Attitude, 372. Alas, Fr Philaret remained in China. The bishops also asked that Abbess Eugenia of Jerusalem should go to India to found a convent and an orphanage. Again, this did not happen, initially due to a lack of funds, and subsequently because of the outbreak of World War II.

Meeting in December, 1936, the Synod of Bishops responded to a request from Fr Andronik that the union of the two Churches should be accomplished quickly. They resolved:

“To ask His Eminence, the President of the Synod, to explain to Hieromonk Andronik that the question of sacramental union with the Syrian Christians, especially before they express recognition of all Ecumenical Councils, is serious enough that it is impossible to decide without other Orthodox Churches and, in particular, the Serbian Church.”[34] GARF, f. 6343, op.1, d.258. cited by Psarev, The Attitude. 373.

Then, in February, 1937, Metropolitan Anastassy, at last, responded to the request of Mar Geevarghese II:

“[Enclosed] in this letter is a copy of the dogmatic decrees and definitions of the Seven Ecumenical Councils translated into English. We will be most happy if your Holiness and the very reverend Bishops of the Syrian Church after considering those decrees and definitions will be able to declare that they hold the same faith as is professed by our Holy Eastern Orthodox Church.”[35] GARF, f. 6343, op.1, d.258. cited by Psarev, The Attitude, 373.

In July, 1937, the Synod of Bishops decided to send Archbishop Nestor Anisimov of Kamchatka (d. 1962) to India in order to establish a Russian Orthodox Mission there. I shall return to Archbishop Nestor’s visit in 1938 after I have given an account of a Serbian visitor to Kerala, Metropolitan Dositheus.

Saint Dositheus the Confessor

Holy Confessor Dosipheus of Сarpatorussia, where he also ministered. A Ukrainian icon of 2013

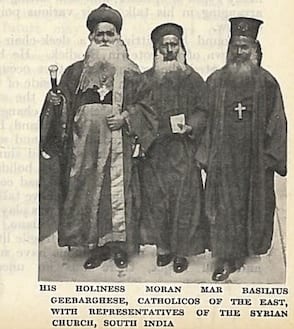

Nine months after the Russian Synod in Belgrade had received the report of Bishop Dimitry, the Serbian Patriarch, Barnabas Rosich (d. 1937) sent Metropolitan Dositheus to negotiate with the Indian Orthodox. Saint Dositheus the Confessor, (martyred 1945)[36] The Holy Confessor Dositheus of Zagreb was glorified in 2000; feastday – 31st December. Metropolitan of Zagreb, the capital of Croatia, was fluent in 5 languages, including Russian and English.[37] “Eighty Years of Indo–Serbian Orthodox Relations & Saint Dositej Vasić of Zagreb.” http://www.spc.rs/eng/eighty_years_indoserbian_orthodox_relations_saint_dositej_vasic_zagreb In the 1920’s, Metropolitan Dositheus, a close friend of the First Hierarch of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia, Metropolitan Anthony Khrapovitsky, laboured intensely to bring comfort and material assistance to the thousands of penniless Russian exiles who had fled the Bolshevik terror and who had subsequently settled in Serbia. Metropolitan Dositheus was frequently sent abroad to represent the Serbian Orthodox Church at international gatherings and, in the winter of 1936-1937, he was sent to India to participate in the 21st World Conference of the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) which was held at Mysore from 2nd January, 1937 onwards. Metropolitan Dositheus was accompanied on his visit to India by Theodore T. Pianov (d. 1969), who was a leader of the Russian Christian Student Movement (RSCM) and an active participant in the Saint Serge Orthodox Theological Institute in Paris.[38] Theodore Pianov worked closely with Saint Maria Skobtsova (martyred 1945) in Paris. During the German occupation of France in the Second World War, Pianov was interred twice by the Nazis. (Fr Andronik in Kerala had retained close links with the St Serge Institute and the RCSM.) After the Conference, for about two weeks they were guests of His Holiness Baselios Geevarghese II, Catholicos of the East and Malankara Metropolitan, at the Old Seminary, Kottayam. According to Buevsky, Metropolitan Dositheus’s purpose in visiting the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church was to continue discussions about a union between the Indians and the Eastern Orthodox but the sources do not suggest any progress in this regard.[39] Buevsky.”The Legacy of the Apostle Thomas.” 51-62.

Oxford, Edinburgh, Paris and Belgrade

At the Faith & Order Conference July 1937

In July 1937, His Holiness Baselios Geevarghese II travelled to Oxford to participate in the two-week-long Life and Work Council. He was one of 300 delegates from 45 countries who represented 120 churches of different traditions. Then Mar Geevarghese II travelled to Edinburgh where he attended from 3rd to 18th August another ecumenical conference, The World Conference on Faith and Order. The Edinburgh Conference brought together 414 delegates from 122 Christian communions in 43 different countries. Also attending both conferences were Fr Georges Florovsky (d. 1979) and Fr Sergius Bulgakov (d. 1944) for Metropolitan Evlogii Georgievskii of the Constantinople Exarchate and ROCOR’s Bishop Seraphim Lade of Potsdam (d. 1950).[40]It is well known that the ROCOR is conservative in its approach to ecumenism. This was not always the case, especially in the 1930’s. See Psarev, A.V. and Kizenko, N. “The Russian Church Abroad, … Continue reading In The Christian East, Canon Douglas wrote:

“The most picturesque figure…was the Syrian Orthodox Catholicos Basileios,[41] This is odd: in this context “Basileios” is a title, not a Christian name. Every Syrian Catholicos has this title. of South India, who with his two Rambans, the Abo Alexios and the Abo Thoma, was the invariable target of the Press photographers. The Abo Alexios, who spent 1936 in England as the guest of the Church of England Council on Foreign Relations, went home with the Catholicos. The Abo Thomas is remaining for a year as the guest of the Cowley Fathers.”[42] J. A. Douglas. “Chronicle and Causerie.” The Christian East, 3 & 4 1937. 72.

The World Conference on Faith and Order was held to explore the possibilities for realizing the unity of Christian churches. When the World Council of Churches (WCC) was established in 1948, the Faith and Order Movement became a part of the WCC, of which the Malabar Syrian Orthodox Church was a founding member.

Following the Edinburgh Conference, Mar Geevarghese II then travelled to Paris where, according to Buevsky, he and Metropolitan Evlogii held discussions about Church unity. Buevsky concludes that these negotiations came to nothing because of the limited circumstances in which Metropolitan Evlogii found himself.[43] Buevsky. The Legacy of the Apostle Thomas. 51-62. Before returning to India, Mar Geevarghese II travelled to Belgrade in Serbia. During September and October Mar Geevarghese II was received in Serbia with great pomp, ceremony and warmth. There he met the ROCOR Synod of bishops and renewed his acquaintance with Metropolitan Anastassy, with whom he had met previously in Jerusalem in 1934.

The Brotherhood of Saint Thomas the Apostle

The Synod of Bishops of the ROCOR were faced with the challenge of how to finance the Mission in south India and Ceylon. In April, 1938, Metropolitan Anastassy wrote to the newly-elected Serbian Patriarch Gabriel Dožić (d. 1950), asking for financial aid. He also wrote in a similar vein to Metropolitan Neophyte Karaabov (d. 1944) of Bulgaria.[44] GARF, f. 6343, op.1, d.258. Cited by Psarev. The Attitude, 374. Then, at the 1938 Pan-Diaspora Sobor, Archbishop Nestor announced that, when he had been in London earlier that year, he had established the Brotherhood of Saint Thomas the Apostle, a charitable organisation with the purpose of providing material support to the Russian Mission in south India and Ceylon. This is the founding charter of the Brotherhood:

“An Orthodox Ecclesiastical Mission has been founded at Malabar, India. The aim of the Mission is to bring the ancient Christian communities of Malabar into communion with the Orthodox Church and to assist them to spread the Christian Faith.

A Brotherhood of St. Thomas the Apostle has been formed with the object of furthering the interests of the Orthodox Mission in India by securing for it moral and material assistance.

The Brotherhood consists of Foundation Members, Honorary Members, and Ordinary Members, all of whom undertake to contribute regular subscriptions to the funds of the Brotherhood. Those members who have signed the original Statute of the Brotherhood will be known as Foundation Members. The dignity of Honorary Member will be conferred upon persons who have rendered exceptional service to the cause of the Mission in India. All Christian men and women who sympathize with the aim of the Brotherhood are invited to participate in the work of the Brotherhood by becoming its Members.

The activities of the Brotherhood are regulated by the Committee of the Brotherhood, consisting of a President, Vice-President, an Honorary Treasurer, and members of the Committee, elected in the first instance by the Foundation Members and on later occasions at the Annual General Meetings of the Brotherhood.

General meetings of all Members of the Brotherhood are to be called on the feast days of the Mission and the Brotherhood, St. Thomas’ Sunday (the first Sunday after Easter) and St. Thomas’ (October 19th), when the Holy Liturgy will be celebrated. It is hoped that all Members will attend the Corporate Celebrations. The Committee may call other general meetings when the necessity arises.

The Brotherhood has the same badge and insignia of two classes as the Mission to India.

In addition to members’ subscriptions the funds of the Brotherhood are raised by collections, lectures, concerts, etc.

The Brotherhood has its own Seal and the above Statute.”[45] Lambeth Palace Library. Douglas 47. ff. 292.

The drafting of the Statute bears all the hallmarks of Serge N. Bolshakoff, the Oxford-based Russian émigré, who was an inveterate organiser of religious organisations.[46] N. Mabin. “Serge N. Bolshakoff – Russian Ecumenist.” https://www.rocorstudies.org/2013/02/09/1302/ His focus on organisational structures, classes of membership, and insignia might obscure the very serious and honourable purpose of the Brotherhood of St Thomas, the inspiration for which undoubtedly came from Archbishop Nestor.[47]Having been ordained as monk-priest in 1907, at the age of 23, Fr Nestor went to Kamchatka in far eastern Russia to begin his missionary service among the pagan peoples of Siberia. It was there that … Continue reading

Thus, it was that in June, 1938, with patronage from the Grand Duchess Xenia, (d. 1960) sister of the Tsar-Martyr Nicholas, that the Brotherhood was established. Archbishop Nestor said at the inaugural meeting,

May, 1938: Archbishop Nestor Anisimov of Kamchatka with the Grand Duchess Xenia at Hampton Court. (Source: Sophia Goodman)

“As the Honorary Members of the Brotherhood, I propose to elect Their Highness Prince Andrey of Russia and Princess Elisabeth of Russia and Their Highness Prince Nikita and Princess Mary of Russia. We will address to His Grace the Lord Archbishop of Canterbury, to His Grace Metropolitan Anastassy, to His Holiness Gabriel the Patriarch of Serbia, who has donated 15,000 dinar, that is £60, for our Mission, to His Grace Metropolitan Stephen of Sofia, who has donated 10,000 levs, that is £20 for the same aim, to His Grace Archbishop Seraphim of Paris and to His Grace Archbishop Seraphim of Boguchary,[48] Archbishop Seraphim (Sobolev) of Boguchar (1881-1950), glorified as Saint Seraphim of Sofia the Miracle-worker; feastday 13th February. who collects the funds for our Mission in his churches, asking them to accept the dignity of the Honorary Members of our Brotherhood.”[49] Lambeth Palace Library. Douglas 47. ff. 292.

In November, 1938, the ROCOR Synod of Bishops resolved to make 25th December the day on which collections would be made in every parish around the world for the specific aim of providing financial support to the Mission in India and in Ceylon.

Russian Episcopal Visits to India

According to J. Boyd, the ROCOR Synod sent to India in 1936 Bishop Victor Svyatin (d. 1963).[50]J. W. Boyd. “Eastern and Oriental Orthodoxy in Chinese Speaking Countries and Their Issues.” http://chineseorthodoxy.blogspot.com/2018/03/eastern-and-oriental-orthodoxy-in.html Boyd, J W. Here … Continue reading From 1933 to 1936 Bishop Victor was Head of the ROCOR Diocese of Peking and China. Boyd suggests that Bishop Victor’s lengthy stay among the Indian Orthodox was for the purpose of holding extended talks with the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church in the hope of forming an “Asian Orthodox Church,” uniting the small Chinese Orthodox Church, perhaps 10,000 souls, with the much larger Indian Orthodox Church. Boyd says that Bishop Victor conducted his missionary work in India between 1936 and 1938, ultimately without success, before returning to China in 1938, in which year he was elevated to the rank of archbishop.

Bishop Victor’s involvement with Indian Orthodox on behalf of the Russian Church is confirmed by Dr Gernot Seide in his 1983 book, Geshichte der Russischen Orthodoxen Kirche im Ausland von der Grundung bis in die Gegenwart:

“In 1932 [Bishop Victor] travelled to Yugoslavia for the Session of the Synod, where he was consecrated Bishop of Shanghai, vicar bishop of China. [In] 1936-38 [he undertook] extensive travels to the Malabar Christians of India and to Ceylon, where he handled the matter of their union with the Church Abroad.”[51]G. Seide. History of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia from Its Beginning to the Present (1983). … Continue reading

However, in his thesis, Fr Andrei Psarev is silent on the interaction of Bishop Victor with the Indian Orthodox.[52] Psarev, The Attitude. Nor, when writing in 1943 about foreign missions of the Russian Orthodox Church, does Bolshakoff mention this extended visit of Bishop Victor.[53] Bolshakoff. (1943).110. Another contemporary writer also fails to mention the visit(s) to Kerala of Bishop Victor. F. E. Keay, writing in 1938, says,

“It is not generally known that the Russian Orthodox Church also is represented in Malabar. At a place called Pattazhi in Travancore, a Russian priest, Father Andronik, has established an ashram. He has recently been joined by another priest of this church named Father Constantine.[54] Schemamonk Konstantin Geshtovt (d. 1956). He stayed at Pattazhy only briefly. In 1936 a Serbian Archbishop with two laymen, one a Rumanian and the other a Bulgarian visited this ashram. Not long ago also it was visited by Bishop Dmitri, Bishop of the Russian Orthodox Church in China, who was on his way back after attending a meeting of the Synod of his church held in Yugoslavia.”[55] F. E. Keay. A History of the Syrian Church in India. (1938. India: SPCK). 105.

Fr Angelos considers the references to Bishop Victor in connection with South India to be erroneous:

“Many articles mention that Bishop Victor (Sviatin) of Peking served as a liaison between the Russian and Indian churches between 1936 and 1938 but there is no mention of this in any primary sources from the period or location and it is my assessment that he never stepped foot on Indian soil.” [56] Stanway. (2019) 36.

However, the visit of another Russian bishop, Archbishop Nestor of Kamchatka, is well documented. It will be recalled that, in the summer of 1937, the ROCOR Synod of Bishops in Yugoslavia, had decided to send Archbishop Nestor to establish a Mission in Malabar and in Ceylon. In fact, Metropolitan Anastassy personally tried to do all he could to support this Mission. He proposed to the Council of Bishops that Archbishop Nestor’s title should be changed to become Archbishop of Colombo and Ceylon, which would enable the Mission to be registered legally.[57] Psarev, The Attitude. 376. A Russian newspaper in London reported in August, 1938, that, after the Pan-Diaspora Council in Yugoslavia,

Vladyka [Nestor] will leave for India in order to unite a Christian community in Malabar to the Orthodox Church. Vladyka will be accompanied by Archimandrite Nathaniel, who is expected to remain in Malabar as a missionary and spiritual guide after they have newly joined the Orthodox Church.[58] Russki v Anglii. August, 1938

In August 1938, accompanied by Fr Nathaniel, Archbishop Nestor travelled to India with the gift of a mitre to present to Mar Geevarghese II.[59] Elpedinsky, Eighteen Years in India. 185. The Times of India reported in August, 1938,

“Archbishop Nestor, of the Russian Church in the Far East, has sailed from London for India to found a mission at Kottayam in Travancore for the Syrian Christians… Archbishop Nestor has founded in England a body called the Brotherhood of St Thomas, consisting of a certain number of well-known Church of England clergymen as well as Russian priests, to organise the mission at Kottayam. The aim of the mission is not to proselytise the Malabar Christians but to help them to develop their native church. The Archbishop believes that a real Indian church is the best hope of Christianity in India. After founding the mission, the Archbishop will leave it under the direction of a dignitary of the Russian Church, probably the Archimandrite Nathaniel.”[60] The Times of India. 11.08.1938. 16.

One wonders how the Indian Orthodox reacted to the idea that the Russians would help them build a “real Indian church.”

By the end of October, 1938, The Times of India was reporting a more tentative approach on the part of the Russian Archbishop “who is now in Kottayam to consider the possibilities of establishing a mission in Malabar.”[61] The Times of India. 28.10.1938. 3. The newspaper noted in the same report that soon the Archbishop would be leaving Kottayam, where he had been the guest of Mar Geevarghese II, and would be travelling to Colombo, Ceylon.

Fr Angelos records that in Colombo Archbishop Nestor was contacted by two groups of people who expressed interest in becoming Orthodox, a group of Anglicans, and, separately, a group of “Independent Catholics”.[62] Stanway. “Perpetual Embers.” 32. The latter group gifted a church building to Archbishop Nestor and the Russian Church. Following a legal dispute and a court case about ownership of the property, the court awarded the building to Archbishop Nestor. However, following the upheavals of the Second World War, the Russian Church was unable to regain the property and eventually it went into the ownership of the Roman Catholic Church.

Buevsky describes Archbishop Nestor’s stay at Kottayam as “short and efficient.”[63] Buevsky, “The Legacy of the Apostle Thomas,” 51-62. Fr Andrei Psarev suggests that Archbishop Nestor did not want to live in India.[64] Psarev, The Attitude. 376. Indeed, before he travelled to India, Archbishop Nestor had suggested to the Synod of Bishops that he should reside in London “since it would be better for him to collect there the financial aid for the mission.”[65] GARF, f. 6343, op.1, d.14. cited by Psarev, The Attitude. 376.

Fr Andronik summarises his rather sanguine view of the ROCOR mission in India:

“Archbishop Nestor, in same way as Bishop Dimitry, went to India with hope for a big and quick success. The reality itself says that the field of activity is big, that potentialities are great, but for success one has to work. There needs to be cooperation by the heads of our Churches, time, and God’s blessing.” [66] Elpedinsky, Eighteen Years in India. 185.

In contrast to the warmth of the meetings with Bishop Dmitri in 1936, the Indians were much cooler towards Archbishop Nestor. They appeared to be more interested in reaffirming their strict adherence to the first three ecumenical councils only and unwilling to consider moving from that position. Fr Angelos notes that Archbishop Nestor had talked to Fr Andronik about his plans for India: he was going “to create a diocese that Included India, Ceylon, and the Malay Archipelago, with the initial nucleus consisting of the four Russian Orthodox communities that Fr Andronik ministered to.”[67] Stanway. “Perpetual Embers.” 33. Perhaps the bishops of the Indian Orthodox Church were less than impressed to hear of plans for yet another parallel jurisdiction on their territory.

After Archbishop Nestor had returned to Manchuria, Fr Nathaniel stayed for a while in Ceylon. However, he did not really engage in missionary work, being more occupied with the Russian and Greek communities in Colombo. Furthermore, the promised financial support for the Mission in India and Ceylon did not materialise. Fr Nathaniel returned to Europe and joined the Monastery of St Job of Pochaev in what is now Slovakia.[68] Birchall, Embassy, Emigrants, 310. In the aftermath of World War II, in the British controlled sector of Germany, he played an heroic role in rescuing Displaced Persons, who were in danger of enforced repatriation to the Soviet Union. In 1946 he became the ROCOR Bishop of Western Europe.

Metropolitan Anastassy reported to the Council of Bishops in September, 1939 about the lack progress with the Mission. The Council decided to release Archbishop Nestor and Archimandrite Nathaniel from their involvement with the Mission. Instead, for the second time, they assigned Archimandrite Philaret Voznesenky to lead the missionary work and to re-energise the Brotherhood of Saint Thomas the Apostle. This did not come to pass, almost certainly because of outbreak of World War II.

Old Catholic Church Building in Ceylon offered to the ROCOR

Appeal to the Patriarch

With the coming of the Second World War, communications were disrupted and contacts between the two Churches ceased. Bolshakoff, writing in his 1943 survey of Russian Orthodox missionary work, observed:

“About fifteen years ago a Russian monk, the Archimandrite Andronicus, came to Malabar and settled among the Syrian Christians. As a result a lively interest for the Orthodox Church was awakened in them. The late Catholicos Mar-Basilios was much attracted by the idea of reaching complete unity with theOrthodox.[69] Mar Geevarghese II was very much alive at this time; he passed away in 1964. He invited two Russian missionary prelates, Bishop Demetrius of Hailar and Archbishop Nestor of Kamchatka, to visit his country. That they did, as well as the Serbian Metropolitan Dositheus of Zagreb. The progress of negotiations was hampered by the present war.”[70] Bolshakoff. The Foreign Missions, 110.

However, Fr Andronik had not yet given up hope. In November, 1943, Fr Andronik managed to establish contact with the newly elected Patriarch Sergei Stragorodsky (d. 1944) in Moscow. Daniela Kalkandjieva confirms tha confirms that “…this archimandrite, who had lost his contact with [Metropolitan Evlogii in] Paris in 1940, asked Sergei for reunion.”[71] D. Kalkandjieva. The Russian Orthodox Church, 1917-1948. (London and New York: Routledge. 2015). 192. At the same time, he sent a detailed report about the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church to the Patriarch.[72] Buevsky. “The Legacy of the Apostle Thomas.” 51-62. In 1948, Buevsky published an account of interaction between the Russian Orthodox Church and the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church in the Журнал Московской Патриархии. He concluded the article by saying:

“Doubtless we shall soon be witnesses of a new and great gift of God, the union of the Indian Syrian Church of the Apostle Thomas with the unique bearer of divine Grace, the Orthodox Church.” [73] Buevsky. “The Legacy of the Apostle Thomas.” 51-62.

His optimistic prediction has not yet come to pass: perhaps the Indian Syrian Church of the Apostle Thomas might have a different perspective on the “uniqueness” of Divine Grace claimed for the Eastern Orthodox Church. Indeed, two years later, in 1950, the key ecumenical officer during Mar Geevarghese II’s pontificate, Fr I. Daniel, published The Malabar Church and Other Orthodox Churches.[74] I. Daniel, The Malabar Church and Other Orthodox Churches (Haripad, Travancore: Suvarna Bharathi Press. 1950). Fr Daniel passed over in silence the interactions of the Russian Orthodox Church with his own Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church.

Conclusion

It seems that there may have been confusion in the minds of the Russian Orthodox as to whether their mission was to convert the Christians of the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church to Eastern Orthodoxy, or whether their mission was to facilitate a union between the two Churches. It may be remembered that when the Indian Orthodox approached the Russians, it was not with a view to being

“converted” but with the purpose of achieving union. Undoubtedly, this misperception of aim and purpose contributed to the failure of the Russian Mission to India.

Perhaps ultimately it was language that was the culprit. As we noted previously, Bishop Dmitri did not speak English. He and other Russian visitors relied on Fr Andronik to translate from Russian into English; then the words of Fr Andronik would be translated into Malayalam, the language of Kerala. However, Fr Andronik was not a native English speaker, having learned English only after his arrival in India, presumably from the Thomas Christians for whom English was a second language. The Indian-Russian negotiations in part focused on theological terms and it is well known how easy it is for misunderstandings to arise: one only has to remember the global consequences arising from varying understanding of terms such as homoousios or filioque. If the Indians had had amongst their number competent theologians who were fluent in Russian, and if the Russians had been able to employ competent theologians who were fluent speakers of Malayalam, perhaps the outcome might have been quite different.

Acknowledgements

I am indebted to His Eminence, Abba Seraphim El-Suriani who has been most generous with his time and his contribution, to whom deep thanks is due. I also thank most warmly Fr Deacon Andrei Psarev of Holy Trinity Seminary, Jordanville, New York, USA for giving me access to his unpublished thesis and his ground-breaking research in the ROCOR archives held in Moscow.

Also, thanks for the kind assistance of: Archimandrite Sergius, Abbot of The Monastery of St Tikhon of Zadonsk, South Canaan, Pennsylvania, USA; Rasophor Monk Angelos, of Holy Trinity Monastery, Jordanville, New York, USA; Ms. Hanna Brightman, London; Dr Alexey Koloydenko, London and Abbess Elizabeth, Jerusalem.

Biographical Note

Nicolas Mabin is a subdeacon at the London Cathedral parish of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia. He has a degree in theology (B.A. Hons) from the University of Kent at Canterbury, UK, and the degree of Diploma in Orthodox Theological Studies, awarded by the Center for Traditionalist Studies, Etna, CA, USA. He is been an enthusiastic and dear friend of this website from its very foundation and the author of his second valuable contribution posted here.

References

| ↵1 | In the 1930’s, what we now call The Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia was known in the UK variously as The Russian Orthodox Church in Exile or the Karlovtsi Synod. Throughout this essay I will use, for ease of reference, the ROCOR. For a concise English-language summary about the ROCOR, see D. Pospielovsky, The Orthodox Church in the History of Russia. (Crestwood, NY.: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press. 1998). 219-227, 294-299. |

|---|---|

| ↵2 | T. Ware, The Orthodox Church. (London: Penguin Books. 1963). repr. 1997. 29. |

| ↵3 | The division between the two non-Chalcedonian Orthodox (Oriental Christians) in India occurred in1912. |

| ↵4 | Divine Liturgy |

| ↵5 | The liturgical language of the Thomas Christians is Syriac, a dialect of Aramaic spoken by the Saviour. |

| ↵6 | N. Hall, “A Visit to the Syrian Christians of Travancore.” The Christian East, 1937. XVII. 1 & 2. 43. |

| ↵7 | S. N. Bolshakoff. “The Syrian Church.” The Eastern Churches Broadsheet. September, 1948. 2-4. |

| ↵8 | E. Smirnoff, A Short Account of The Historical Development and Present Position of Russian Orthodox Missions (1903. London: Rivingtons). |

| ↵9 | See C. J. Birchall. Embassy, Emigrants, and Englishmen: The Three Hundred Year History of a Russian Orthodox Church in London. (Jordanville, New York: Holy Trinity Publications, 2014). 170. |

| ↵10 | S. N. Bolshakoff, The Foreign Missions of The Russian Orthodox Church. (1943. London: SPCK.) |

| ↵11 | N. Zernov, The Christian East: The Eastern Orthodox Church and Indian Christianity. (Delhi: SPCK, 1956). |

| ↵12 | A. Stanway, “Perpetual Embers: A Chronicle of ROCOR’s Missionary Efforts in India.”15.https://www.academia.edu/38192487/Perpetual_Embers_A_Chronicle_of_ROCOR_s_Missionary_Efforts_in_India |

| ↵13 | A. S. Buevsky, “The Legacy of the Apostle Thomas (in Russian).” Журнал Московской Патриархии, 51-62. |

| ↵14 | Buevsky, “The Legacy of the Apostle Thomas,” 51-62. |

| ↵15 | Stanway. “Perpetual Embers.” 25. |

| ↵16 | The Times of India. 12.02.1937. 3. |

| ↵17 | “Eighty Years of Indo–Serbian Orthodox Relations & Saint Dositej Vasić of Zagreb.”http://www.spc.rs/eng/eighty_years_indoserbian_orthodox_relations_saint_dositej_vasic_zagreb (March 2019). |

| ↵18 | Andronik Elpedinskii, Eighteen Years in India; repr. 2012. Восемнадцать лет в Индии. Moscow: Сретенский монастырь. |

| ↵19 | “Baselios Geevarghese II.”https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baselios_Geevarghese_II |

| ↵20 | Buevsky, “The Legacy of the Apostle Thomas,” 51-62. |

| ↵21 | Buevsky. “The Legacy of the Apostle Thomas.” 51-62. |

| ↵22 | “Perpetual Embers.” 8. |

| ↵23 | “Посещение Южной Индии епископом Димитрием.” Церковная жизнь. 1936: 4-5. 73. cited by A. V. Psarev in The Attitude of The Russian Orthodox Church Abroad Toward Non-Orthodox Christians and the Ecumenical Movement (1920-1964): An Historical Evaluation. Thesis Submitted for the degree of Master of Theology, St. Vladimir’s Orthodox Theological Seminary, Crestwood, New York, 30th April 2004. Chapter VI: “Relations with Oriental Orthodox Churches.” |

| ↵24 | Psarev. The Attitude. 369. |

| ↵25 | Gosudarstvennyi Arkhiv Rossiiskoi Federatsii [GARF] f. 6343, op. 1, d. 257. cited by Psarev, The Attitude, 370. |

| ↵26 | GARF, f. 6343, op.1, d.257. cited by Psarev, The Attitude, 371. |

| ↵27 | Stanway. “Perpetual Embers.” 9. |

| ↵28 | Elpedinsky, Eighteen Years in India, 166. |

| ↵29 | Elpedinsky, Eighteen Years in India, 166. |

| ↵30 | Psarev, The Attitude, 371. |

| ↵31 | Letter dated 31st March, 1936.Gibbes, N. Unpublished letter, dated 31.3.1936: St. Nicholas Parish Archive, Oxford. |

| ↵32 | GARF, f. 6343, op.1, d.258. cited by Psarev. The Attitude, 372. |

| ↵33 | Psarev. The Attitude, 372. |

| ↵34 | GARF, f. 6343, op.1, d.258. cited by Psarev, The Attitude. 373. |

| ↵35 | GARF, f. 6343, op.1, d.258. cited by Psarev, The Attitude, 373. |

| ↵36 | The Holy Confessor Dositheus of Zagreb was glorified in 2000; feastday – 31st December. |

| ↵37 | “Eighty Years of Indo–Serbian Orthodox Relations & Saint Dositej Vasić of Zagreb.” http://www.spc.rs/eng/eighty_years_indoserbian_orthodox_relations_saint_dositej_vasic_zagreb |

| ↵38 | Theodore Pianov worked closely with Saint Maria Skobtsova (martyred 1945) in Paris. During the German occupation of France in the Second World War, Pianov was interred twice by the Nazis. |

| ↵39 | Buevsky.”The Legacy of the Apostle Thomas.” 51-62. |

| ↵40 | It is well known that the ROCOR is conservative in its approach to ecumenism. This was not always the case, especially in the 1930’s. See Psarev, A.V. and Kizenko, N. “The Russian Church Abroad, the Moscow Patriarchate, and Their Participation in Ecumenical Assemblies during the Cold War, 1948-1964” In North American Churches and the Cold War, by P. B. Mojzes. (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans. 2016.) 326-341. |

| ↵41 | This is odd: in this context “Basileios” is a title, not a Christian name. Every Syrian Catholicos has this title. |

| ↵42 | J. A. Douglas. “Chronicle and Causerie.” The Christian East, 3 & 4 1937. 72. |

| ↵43 | Buevsky. The Legacy of the Apostle Thomas. 51-62. |

| ↵44 | GARF, f. 6343, op.1, d.258. Cited by Psarev. The Attitude, 374. |

| ↵45 | Lambeth Palace Library. Douglas 47. ff. 292. |

| ↵46 | N. Mabin. “Serge N. Bolshakoff – Russian Ecumenist.” https://www.rocorstudies.org/2013/02/09/1302/ |

| ↵47 | Having been ordained as monk-priest in 1907, at the age of 23, Fr Nestor went to Kamchatka in far eastern Russia to begin his missionary service among the pagan peoples of Siberia. It was there that Fr Nestor conceived the idea of a charitable brotherhood to support the Kamchatka mission. With strong support from individual members of the Imperial Family, including the Tsarina and the Grand Duchess Elizabeth (and despite opposition from the Church bureaucracy), in 1910 he established in Vladivostok the Charitable Kamchatkan Brotherhood with branches in Moscow, St Petersburg, and Kiev. The Brotherhood provided funds and assistance that built many churches, schools, and hospitals in Kamchatka. In 1918 Bishop Nestor was the first Russian bishop to be arrested by the Bolsheviks but he escaped to Manchuria, where he maintained the title of the Bishop of Kamchatka and Petropavlovsk.” |

| ↵48 | Archbishop Seraphim (Sobolev) of Boguchar (1881-1950), glorified as Saint Seraphim of Sofia the Miracle-worker; feastday 13th February. |

| ↵49 | Lambeth Palace Library. Douglas 47. ff. 292. |

| ↵50 | J. W. Boyd. “Eastern and Oriental Orthodoxy in Chinese Speaking Countries and Their Issues.” http://chineseorthodoxy.blogspot.com/2018/03/eastern-and-oriental-orthodoxy-in.html Boyd, J W. Here Boyd cites: Anonymous. Irénikon. vol. 12. 1936. 185. This citation is perplexing. Volume 12 is 1935. On p.185 of vol 12 is a list of ROCOR bishops including Victor du Pekin, but there is nothing about connections between the Missions in China and in India.

Page 185 in vol. 13 (1936) is concerned with the Sophiology of Fr Bulgakov. |

| ↵51 | G. Seide. History of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia from Its Beginning to the Present (1983). https://www.rocorstudies.org/2012/02/15/gernot-seide-history-of-the-russian-orthodox-church-outside-russia-from-its-beginning-to-the-present-1983/. Part VI. 140. (accessed October, 2018). |

| ↵52 | Psarev, The Attitude. |

| ↵53 | Bolshakoff. (1943).110. |

| ↵54 | Schemamonk Konstantin Geshtovt (d. 1956). He stayed at Pattazhy only briefly. |

| ↵55 | F. E. Keay. A History of the Syrian Church in India. (1938. India: SPCK). 105. |

| ↵56 | Stanway. (2019) 36. |

| ↵57 | Psarev, The Attitude. 376. |

| ↵58 | Russki v Anglii. August, 1938 |

| ↵59 | Elpedinsky, Eighteen Years in India. 185. |

| ↵60 | The Times of India. 11.08.1938. 16. |

| ↵61 | The Times of India. 28.10.1938. 3. |

| ↵62 | Stanway. “Perpetual Embers.” 32. |

| ↵63 | Buevsky, “The Legacy of the Apostle Thomas,” 51-62. |

| ↵64 | Psarev, The Attitude. 376. |

| ↵65 | GARF, f. 6343, op.1, d.14. cited by Psarev, The Attitude. 376. |

| ↵66 | Elpedinsky, Eighteen Years in India. 185. |

| ↵67 | Stanway. “Perpetual Embers.” 33. |

| ↵68 | Birchall, Embassy, Emigrants, 310. |

| ↵69 | Mar Geevarghese II was very much alive at this time; he passed away in 1964. |

| ↵70 | Bolshakoff. The Foreign Missions, 110. |

| ↵71 | D. Kalkandjieva. The Russian Orthodox Church, 1917-1948. (London and New York: Routledge. 2015). 192. |

| ↵72 | Buevsky. “The Legacy of the Apostle Thomas.” 51-62. |

| ↵73 | Buevsky. “The Legacy of the Apostle Thomas.” 51-62. |

| ↵74 | I. Daniel, The Malabar Church and Other Orthodox Churches (Haripad, Travancore: Suvarna Bharathi Press. 1950). |

Time has come to forget about the semantic differences between two factions of Orthodox Church

and establish intercommunion and show a unified force in the troubled world order

PK George

One cannot be Orthodox without full acceptance of the Faith, including the dogma and Holy Canons of all seven Ecumenical Councils. In fidelity in Communion with the Orthodox Catholic Church. Therefore, intercommunion with Non Chalcedonian bodies does indeed call for their “conversion” or repentance and return to the Church. The Fifth Ecumenical Council serves as the Orthodox foundation of such intercommunion and presents Orthodox, Cyrillian christology, reconciling the various “miaphysite” Confessions of Faith used by Non Chalcedonian local churches with the Orthodox christology of Chalcedon. What reunion would look like would, of course, entails Orthodox welcoming of venerable rites other than the Byzantine, where such things as theopaschite seepages into liturgical prayer will be excised, azymes will be rejected where they are used, musical instruments where in use in worship will end. Deaconesses and other hierofeminist intrusions where occurring will come to an end. The personages of Diodoros, Severus, James Barradaeus et al will need to be approached by the Orthodox with greater sensitivity tempered with economy so that a proper integration of other figures of piety from Non Chalcedonian churches may possibly be included in universal, Orthodox veneration. The calendar used may be the Church Calendar of Nicea or the Revised Julian Calendar, where observance of the Nicean Paschalion is practiced by all. Most importantly, autocephalous, Non Chalcedonian churches will need to retain their autocephalous status, where the Russian church and other local churches in Communion with her in the Orthodox Catholic Church embrace Non Chalcedonian local churches and their faithful as brothers, opening our doors and hearts to them, guiding them in their transition in Orthodox reunion. In the instance of the Antiochian and Alexandrian Non Chalcedonians, reunification with Chalcedonian sees will be facilitated by dual ritualism, where the predominant rite and administration will eventually become the one heading reunited Patriarchates. Even when it means the end of Hellenist administrations. The case of the Patriarchate of Jerusalem will require much prayer, humility and Pan Orthodox discussion. Chalcedon’s disciplinary elevation of the See of Constantinople, junior theretofore to the venerable sees of Alexandria and Antioch, should be reevaluated, especially in light of the fact that the city of Constantinople no longer exists. So, yes, a working model of imminent Orthodox reunion and intercommunion must and can be offered. Reunion in Orthodoxy is what indeed we all hope and pray for.

Good reading