Helena (Alyona) Kojevnikov was born in the former Yugoslavia, then spent her early years in Displaced Persons camps (Moenchehof and Schleissheim) in the American zone of occupied post-war Germany. In 1950 the family emigrated to Australia, where she ultimately read Russian Language and Literature at Melbourne University. In 1971 she was offered a position on the Russian news desk of Radio Liberty in Munich, West Germany. Among other duties, she participated in the Russian religious program of RL. In 1978 she relocated to London to work for Keston College, and also to freelance as the presenter and co-author of the weekly religious program of the Russian Service of the BBC, which made her a household name in Russia in the 1970s-1980s. We have asked Alyona to share her memories about one of the best-known archbishops of the Moscow Patriarchate in the XX century, Metropolitan Anthony (Bloom) of Sourozh (+2003) with whom she worked on the BBC religious program for many years.

Alyona, you moved to work in London, where you joined the parish of our Russian Church Abroad while employed as the London correspondent of Radio Liberty and recorded Metropolitan Anthony’s weekly talks for inclusion in the Radio Liberty and BBC Russian religious programs, a unique opportunity at that time. How was it for you, someone who had been born and raised in the RO Church Abroad, to come into such close contact with a priest of the “Soviet Church”, a metropolitan, whom you discovered for yourself, and saw in him a reflection of Our Lord? This is a very unusual experience. Your story breaks the mold, as they say.

I met Metropolitan Anthony in 1978 when I came to London as a journalist and to work for Keston College. This was an academic research institution founded by an Anglican priest, Michael Bourdeaux, which studied the situation of believers in communist countries, including the then USSR. I was born into and grew up in the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad (later renamed the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia – ROCOR). Naturally, I began to attend the ROCOR church in London. Yet literally a few weeks after my arrival in London, the wife of Fr Vladimir Rodzianko (later Archbishop Vasiliy) died suddenly. She had been the presenter of the BBC Russian religious program for many years, and someone had to be found urgently to replace her as presenter and co-author of the program. As I had already worked on the Russian religious program of Radio Liberty, the position was offered to me. This is how I came to meet Metropolitan Anthony, who gave weekly talks on the BBC religious program. These talks were always the opening segment of the program. Thus it came that for the first time in my life I crossed the threshold of a church of the Moscow Patriarchate.

I would say that even one meeting with Vladyka Anthony would be enough to leave a lasting impression for one’s entire life – he was a pillar and affirmation of Truth. It is said that St Seraphim of Sarov used to meet every person who came to him with the words: “Greetings, my joy!” Vladyka did not echo these precise words, but it was with real, shining joy that he met everyone without exception. I have never encountered anyone like him in my life, either before or since. He was like a ray of light in the darkness, I would say that everyone who met Vladyka, went away enlightened. At first, I thought it might be a problem for me, finding myself caught between the Church Abroad and the Moscow Patriarchate, but just at that time problems arose within the Church Abroad parish as the lease on the building it had used for many years had expired. A plot of land had been purchased in the suburb of Chiswick for a new church but work on its construction had not yet begun. I had attended church all my life, and it was an essential part of my being. I began to attend the cathedral in which Metropolitan Anthony served, first of all, because there were no canonical differences between the two jurisdictions. The main thing, in my view, was to pray to God more, and pay less attention to human quarrels and transient political situations.

Metropolitan Anthony had built up a truly unique parish. I do not think there was another like it. Over the 15 years that I was a parishioner there before being posted to work in Moscow, I do not recall any conflicts whatsoever. This may be hard to believe, but it is true. Vladyka simply never allowed such situations to arise. There is a rather crude Russian saying: “How the priest is, so is the congregation”, but the derogatory word “pop” is used instead of the word “priest”. I think the absence of discord was in a great measure due to the fact that we all wanted to try to be like Vladyka to the best of our ability. He was a person of very wide views. For instance, he was very well disposed toward the ROCOR. I recall him saying that the publishing activity of Jordanville was superb by comparison with that of the Moscow Patriarchate: “If only for its publishing program, the Church Abroad is dear the Lord God” he said, because it accomplishes such a great task. As already mentioned, Keston College studied the situation of believers in all communist countries, but as the only native Russian speaker and Orthodox Christian on the staff, I paid particular attention to the then Soviet Union and the fate of the Russian Orthodox Church, which was my special concern. As at that time there was a considerable number of Christians confined in Soviet camps, prisons and psychiatric institutions in the USSR, Keston College organized a service of intercession (moleben) to pray for them. A suitable date for this service was chosen, I think it was the date for the commemoration of the New Martyrs, and we asked Metropolitan Anthony to officiate at this service, which was held in the famous church of St Martin-in-the Fields near Trafalgar Square. At the time there were quite a few Orthodox prisoners of conscience, such as Fr Dmitri Dudko, who were suffering for their faith and the witness they bore. Vladyka served this moleben, reading out the names of all the prisoners from a list we drew up for him. I heard later, though I do not vouch for the accuracy of this information, that Vladyka subsequently had serious difficulties with the Moscow Patriarchate because the moleben was reported in the leading newspapers. After the moleben Vladyka spoke movingly, as always. No matter who may claim what, in all the years I was associated with him closely, I never saw, or never heard him utter a word of disparagement about the ROCOR.

Prejudice?

Possibly prejudice by some. He was, after all, from the first emigration, and people of his generation often held differing views. This year will be the 100th anniversary of his birth.

At the Church Council in 1970 he, together with Archbishop Vasiliy of Brussels, spoke out against the severe sanctions toward the ROCOR. “Because our churches are located in nearby neighbourhoods these [sanctions] only exacerbate the situation if actions such as anathemas and similar measures are invoked.” This shows the disapproval of our emigres who are under the Moscow Patriarchate.

He ascribed very little importance to the differences. Vladyka often wrote, and those who have heard him speak will know, he explained his stance by saying that the Russian Orthodox Church [in Russia] is in a situation of dire plight. After all, it is a driven church. We must not look at official declarations, the World Council of Churches and so forth. It is obvious where that springs from. How can one desert one’s mother, he would say? Even if she has sunk to the lowest depths, even if she lies in the gutter? That is the time when she stands in greatest need of your support and love than if she was well and good. There were many who disagreed with this stance. Yet Vladyka remained firm in his conviction, without any feelings of hostility toward the ROCOR. In all the 25 years that I worked closely with him and saw him on a practically weekly basis to record his talks, he never uttered a negative word about the ROCOR.

It is also said that Vladyka was a monarchist by personal conviction.

Yes, that is quite true. We had spoken about that because my grandparents were, naturally enough, monarchists, while I am not. I once loaned Vladyka some copies of the Pravoslavnyi Put’ [Orthodox Way], published in Jordanville. I had received them from Archbishop Laurus, who helped me with literature which at that time I was able to get into Russia by various means. Some of these issues, bound into annual volumes, were duplicates which I loaned to Vladyka. Several of them contained the diaries of Tsar Nicholas II and his wife, already imprisoned in exile. “Have you read them carefully?” Vladyka asked me. When I answered that I had not, he said: “You think this is all politics, don’t you? Maybe so, maybe not. But you read them, and you will see how just it is that he and the empress have been glorified alongside the New Martyrs. Because no matter what human weaknesses they may have had, profound enlightenment shines forth from these diaries and letters…Yes, I am a monarchist, and will always be one.”

Did he revere the Tsar?

Absolutely. “You sit down and read [the diaries] attentively, not from a critical point of view, politics or historical events, but approach them as a manifestation of a human soul” he instructed.

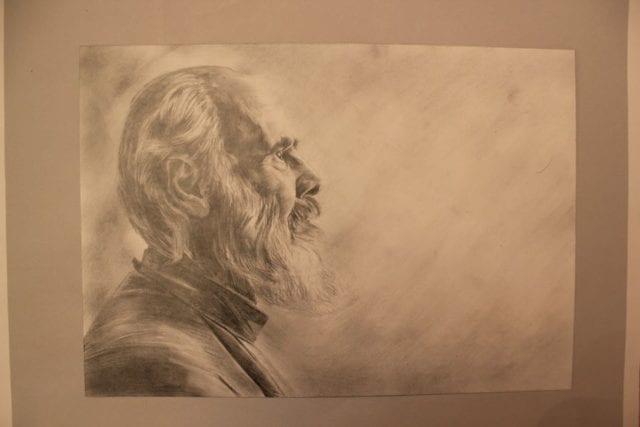

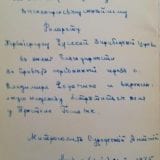

Dedication on the book by A. Shumkina. “Muscovite Russia: An aid to [the study of] the History of Russian Culture”, Paris, 1974. To His Eminence Filaret, First Hierarch of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia, in gratitude for the greetings conveyed by Fr Vladimir Rodzianko and the expressed hope of a meeting before the Throne of God. Metropolitan Anthony of Sourozh, London 3. iv (sic) / 21 (iv), 1975. In a report to the Bishops’ Council of the ROCOR on 30 September 1976, Metropolitan Filaret mentioned the receipt of this book and said that according to Archpriest V. Rodzianko, Metropolitan Anthony was considering joining the ROCOR

The ROCOR has St John of Shanghai, a saint also from the first emigration, who was a bishop of the Moscow Patriarchate. They are alike in that they both served their people, dedicated themselves [to this service]. You have said that Metropolitan Anthony maintained the monastic vow of poverty in full, he had no material possessions.

Exactly! “I am a monk” he would say. I know from my ex-husband, who was a producer of the BBC religious program and would occasionally be the one to tape Vladyka’s talks, that Vladyka lived in a tiny room (cell) behind the altar, that contained a camp bed, a bedside table, and a pair of carpet slippers. Nothing more. Under this cell was a pump regulating one of the underground rivers, of which there are many in London, and every 15 minutes the pump would thunder into action – boom, boom, boom! Having heard this, I asked Vladyka: “Surely something better can be arranged for you? Nikolai says…” “What are you talking about?” Vladyka demanded. “I’m a monk! I have forsworn all material possessions and I have all that I need.” He was indeed a true monk. Not long after I came to London, I attended a church service at the Ennismore Gardens cathedral. Shortly afterward, we were talking about something, and Vladyka said: “Can you imagine it? I have become a very rich man!” “What?” I asked, stunned. “I have started receiving an English pension!!” It must be said that pensions paid to the clergy in England have to be studied through a microscope. Quite by chance, I found out later (he would never have told me this) that he did not keep a penny of that pension but gave it all away to needy people in the parish. He would never have changed his tiny cell for anything else. He subsisted on small salads that people would leave for him near the presbytery. He did not normally eat meat, said he simply had no taste for it, but he was not a crusading vegetarian. On many occasions when I came to tape his talk, I would find him down on hands and knees, scraping candle wax off the church floor. I once said that surely somebody else could do this job, the Parish Sisterhood, for instance. “Nonsense!” he replied. “ This is my duty. I live here, and it is up to me to keep everything in order.” Show me another metropolitan who would go down on all fours to clean candle wax off the church floor! I don’t believe there is one.

I think our Metropolitan Hilarion might.

Hopefully, he would! Valdyka saw no need for any assistance. And thank God for it! He was genuinely surprised by my suggestion. It was his home, and he would look after it. He did not have the slightest desire or interest in any luxuries. None whatsoever. “When I became a monk, I left all worldly goods behind me. I have none, and I want none!”

In other words, he found his way to discover Christ? It has been said that a certain Metropolitan Anthony cult developed around him. What can you say about that?

I am absolutely certain that if that was the case, Metropolitan Anthony would have put a speedy end to it. It is known that something like that occurred regarding St John of Kronstadt while he was still alive, and Fr John suppressed all such attempts very firmly. I’m sure that Vladyka would have been horrified at any similar manifestations. I was working in Moscow when I received the news that Vladyka had passed away. I have heard a lot of people saying that when they die, they want to be buried in the Russian soil. I once asked Vladyka how he felt about this? “You know,” he said, “I could not care less where this body, for which I will have no use, goes.” Years later back in London, I saw a TV program featuring some newly-arrived Russian standing by Vladyka’s modest little grave and proclaiming indignantly; “What’s this? You call this a grave suitable for a metropolitan? This bit of earth, flowers, a small surround? He needs a proper MON_U_MENT!!” I recall Vladyka saying that he wants no monument over his grave; “Is somebody afraid that I will climb out of my grave at night and terrify people?” At first, this did not happen: the little grave, which always had flowers blooming on it no matter what the time of year, was a bright spot of colour from the moment you entered the Old Brompton Cemetery with its grey tombstones of bygone days.

Thank you, Alyona for sharing your memories of Metropolitan Anthony with us. But why is it that in his relations with people, if one may say so, did he teach or taught? What lesson could be drawn by those who came to see him?

He made every person feel that he is worth something, that he is unique, that he is important, just as we are all important to Christ. And he managed to remind us, make us feel that we are not insignificant beings, but that we have real value.

In other words, this was not some managerial method or professional approach, he really reached out to everyone equally?

Yes. He greeted one and all with true joy, one that made you straighten your back and stand taller, and this means a great deal.

Alyona, thank you very much. May God grant you many years and strength. I am very glad that we have had this discussion. I hope that we shall continue it another time.

Thank you, Father Andrei.

Conducted by Deacon Andrei Psarev

LINKS

Alena Kozhevnikova, Invariably the “Russianness,” is Going to Dissipate With Every Congregation