Part II, Chapter 4

The Rebuilding of Church Life since 1950

In 1945, the Synod had 350 communities in North America. Through the influx of refugees from Europe and the Far East, the existing communities were numerically strengthened. However, numerous new communities were also established, as the refugees often resettled in large self-contained groups. [1] “Kirche in Nordamerika. Geschichte,” in HK (1949) pp. 135-139; “Lage in Nordamerika” in HK (1954) pp. 140-142.

The renewed schism of the Metropolia posed a danger to the Church Abroad for a time, in that the latter could have lost its influence over church life in America. In contrast to the mere 70 communities which had remained with the Church Abroad, 300 communities belonged to the Metropolia at the end of the 1940s. Thus, for the newly arrived refugees, the possibility of joining a Metropolia community was much greater than that of joining a Synodal one. Nevertheless, the Church Abroad strengthened its position in subsequent years and established new communities. In addition to both exile groups, however, since 1946 the Moscow Patriarchate again entered the stage as a rival. The success of the Patriarchate – in 1946 only 6 communities – is partly explained by the vacillating attitudes of the Metropolia towards the Patriarchate during the years 1944-46. After having achieved initial recognition, numerous communities refused to participate in the renewed break and remained under the jurisdiction of the Patriarchate, which in the mid-1960s had some 80 communities in the United States and Canada, and with the granting of autocephaly to the Metropolia gained yet another 60 or so communities. [2] Orthodoxy in America. Some statistics in: ECR (1968) pp. 70-73; Yearbook of American and Canadian Churches (1978), pp. 87, 127.

The strengthening of the position of the Church Abroad in North America was due to various circumstances; as in 1927, a portion of the clergy and communities remained faithful to the Church Abroad. The 70 or so communities that remained form the basis for the present community life in North America. They were the same communities that had belonged to the Church Abroad at the time of the death of Archbishop Apollinarius in 1933. At that time, the Synod of Bishops had had 64 communities.

To these “old communities,” however, new communities were quickly added. These consisted mostly of refugees who were arriving from Europe and the Far East. In 1952, the Church Abroad had approximately 100 communities there, today [trans., 1983] there are 143. [3] Severnoi Ameriki, p. 210; Spisok (1981) pp. 3-18. The refugees who came to North America beginning in 1945 felt closer to the Church Abroad than to the Metropolia or even the Patriarchal Church. The Church Abroad had given them spiritual care in Europe and the Far East after their expulsion. Now the Church leadership strove to help build up Church life by sending priests to the new communities. Thus, the Church Abroad had an advantage over the Metropolia in America, and even over the Paris Jurisdiction in Europe, in that at that time the Church Abroad had more than enough priests since almost all of the refugee clergy had been under the jurisdiction of the Church Abroad. The uncompromising anti-Communist stance of the Church Abroad was essentially closer to the political convictions of these émigrés than the vacillating stance of the Metropolia’s leadership. Similarly significant was the fact that many Metropolia communities were using English as the liturgical language in the place of Church Slavonic in the divine services. These communities did not represent the new émigrés the Russian Church whose children they considered themselves to be.

The situation of the expelled monastic communities paralleled that of the clergy and laity. When one looks at isolated monks and nuns, one sees that only a small group of four nuns under the direction of Mother Juliana of Harbin joined the Metropolia. In 1949, when they arrived in California, they were given a building in Calistoga, in which they founded the convent of the Dormition of the Theotokos. [4] Tarazar, p. 302. These sisters, however, had no knowledge of the jurisdictional situation in North America in 1949, because developments in the United States after 1945 were certainly not known to them.

In the other countries – in South America and Australia – the situation was even more favorable for the Church Abroad, which was either the only Russian Church in these countries or, in the case of newly-founded communities, the only one which was in the position to send a priest. Schisms form the Church Abroad, such as the one in Argentina, where Archpriest Izraztsov joined the Metropolia in 1947, remained a rare exception. In Australia and New Zealand, the Russian Church was only represented by two communities. Of the 61 communities today in South America, Australia, and New Zealand, almost all were founded after 1945. [5] Spisok (1981) pp. 28-32.

Thus, the starting position of the Church Abroad in the territories overseas after 1945-49 was essentially more favorable than one might assume. Until the mid-1950s, the number of communities grew steadily worldwide and reached around 500 at its high point. Since that time, however, the number has decreased, finally standing at about 350 communities. This has changed little in the 20 years since. The abandonment of over 100 communities has had various causes. The complete dissolution of the refugee camps in the Far East (in the Philippines, Taiwan, and Hong Kong) and Europe (in Germany, Austria, and Italy) led to the closure of numerous parishes in these countries. After the closure of the refugee camps, small parishes existed for a while and consisted of only a few families that had remained in neighboring communities; subsequently, they were also dissolved. Some of the smaller diaspora communities had to be abandoned in Asia, Africa and parts of South America, because, through assimilation, emigration and the aging (of the faithful), the communities had dissolved by themselves. Such developments have, for example, also been typical of some communities in North America, where since the end of the 1950s many émigrés have moved away. The number of communities also decreased because of financial considerations. Inasmuch as the parish church was housed in rented or leased buildings, smaller communities were often unable to meet the rent and were forced to assimilate with larger communities. There have also been cases, of course, where the building or plot of land had previously only been rented, but subsequently were sold by the owners, forcing the closure of the churches and chapels. There have even been cases where the churches were closed for reasons of safety, as in the case of the Cathedral of the Ascension in the Bronx (New York). This was the old cathedral from the time of Archbishops Apollinarius and Vitalis. After clergy and the faithful had been attacked on numerous occasions, parishioners no longer got married in the church. Finally, the church had to be closed as a result of the growing crime rate in the Bronx.

The growth of the communities and the influx of refugees to the United States after 1948 led the Church leadership to consider moving its headquarters there. The principle difficulty was finding their own building, which had to be in or near New York, in order to transfer the administration of the Church Abroad there. Bishop Seraphim (Ivanov) was charged with the planning and search. The Holy Trinity Monastery in Jordanville, which was gradually developing into the spiritual and theological center of the Church Abroad, and since 1948 has accommodated a seminary for priests, was of central significance for the Church, but the premises available there were insufficient. Due to the influx of 20 monks from Europe and the Far East, the accommodation of the seminary and its students, and the further establishment of the printing press, the spatial capacities of the monastery were entirely exhausted. The main buildings housing the monastic cells and the administrative offices were built only in 1954-57. Thanks to the support of Prince Beloselsky-Belozersky, who expressed his readiness to sell his estate in Mahopac, New York, some 40 miles north of New York City, the Church was able to purchase a freehold plot of land adequate for a monastery and to which the Synod of Bishops and the First Hierarch could move. The transfer of this property took place in December of 1949. The renovation of the main building and the erection of a small church were completed in November of 1950, a few days before the arrival of Metropolitan Anastasius. On 23 January/5 February 1951, the wonderworking Kursk Icon of the Mother of God arrived in New York from Germany and was installed in the new monastery, which was to be the headquarters of the Synod. The New Kursk-Root Hermitage was reminiscent of the former monastery near Kursk in which the Kursk Icon had been venerated before the Revolution. [6] Cf. Part IV, Chap. 2; Russ. Prav. Ts. 1, pp. 482-505.

The New Kursk-Root Hermitage remained the headquarters of the Synod until 1957. Though the monastery was only a residence, it was still located too far outside the city. For this reason, a second residence for the winter months was sought in New York City, which was finally found in 1952 at 312 West 77th Street in Manhattan. The building was small and housed the chancery and a house chapel. [7] Prav. Rus’ (1952) 4, p. 15. It was indeed nearer to the faithful, but its limited space meant that it could only be a temporary solution. The house chapel was too small to accommodate all the worshippers at the divine services.

Finally, in 1957, a freehold building was acquired at the corner of Park Avenue and East 93rd Street in an elegant residential section of Manhattan. Thanks to the financial assistance provided by Serge I. Semenenko (1903-1980), [8]The parents of J. Semenenko had been friends of Metropolitan Anastasius from pre-revolutionary times. Their son had become vice president and director of the First National Bank of Boston and had … Continue reading who not only offered the money to purchase the building and land but also the means to convert and restore the house, Metropolitan Anastasius and the Synod was able to move into the new building. [9] Prav. Rus’ (1958) 3, p. 10; Russ. Prav. Ts. 1:181-198. In the building with its over forty rooms, were located the residence of the First Hierarch and the Chancery of the Synod, along with the archives, assembly halls, two churches, and the Synodal high school. In a spacious side wing, the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Sign (the Kursk Icon) was established. On the ground floor of the main building is the Chapel of St. Sergius of Radonezh. In this church, the divine services are held daily, in Church Slavonic on weekdays and in English on Sundays. In the cathedral, divine services are held on the twelve great feasts and other important feasts and on Sundays. The iconostasis of the cathedral was painted by the monastic iconographers Cyprian (now Archimandrite) and Alypius (now Bishop of Chicago), who for this work was awarded the golden cross. The consecration of the Cathedral took place in October of 1959. [10] Tserk. Zhizn´ (1959) 5-6, pp. 65-66; 9-10, pp. 143-144. The two monks also painted the iconostasis of the St. Sergius Church in the style of 18th-century Russian iconography. The royal doors of this iconostasis came from a Russian village church and had been brought out of the Soviet Union by some refugees. The completion of the sides of the iconostasis in the same style as these royal doors represents the especially successful work of both iconographers.

The Wonder-Working Kursk Root Icon is housed in the Synodal building in New York in the Metropolitan’s private quarters. It is brought daily to church for the divine services in order to give the faithful the opportunity to entreat the protection of the Mother of God before it. At the end of the divine service, the icon is replaced by a copy (or another icon of the Mother of God, in particular, the Wonder-Working Icon “The Joy of All Who Sorrow” from Harbin). The consecration of the new Synodal building took place in October of 1959, during a Council of Bishops. Since then the Church Abroad, of all the Orthodox jurisdictions in North America, has at its disposal the most commodious accommodation. In 1952, the faithful in California obtained a building in Burlingame, in which a second summer residence was established for Metropolitan Anastasius. In 1964, in place of this building, a new building was consecrated, in which the Church of All Saints of Russia, the quarters of the Metropolitan, a chancery and a small elementary school were located. [11] Russ. Prav. Ts. 1:505-507. In this metochion, the First Hierarch spent the summer months; though from the mid-1970s Metropolitan Philaret spent most summers at the Lesna Convent in France until he became too ill to travel such distances.

The move of the Synod to the United States indubitably strengthened the position of the Church Abroad in North America. The sessions of the Council of Bishops, which met every three years, were held thereafter in North America: from 1957 in the New Kursk-Root Hermitage and then from 1959 in the Synodal building in New York. Only the Councils in 1971 and 1974 took place elsewhere: in 1971 in Montreal, [12] Pamyatka 50-letiya, pp. 49-64. and in the second case at the end of the Third Pan-Diaspora Council in Holy Trinity Monastery.

The Metropolia saw this move to America above all else “as an aggressive act.” [13] Prav. Rus´ (1950) 23-24, p. 29; (1951) 6, p. 3. The position of the Metropolia, which claimed to be the only representative of all the Orthodox, was not sufficiently well-rooted. Many of the faithful had turned away from it and joined the Moscow Patriarchate. Their First Hierarch of many years, Metropolitan Theophilus, died in 1950. His successor was Metropolitan Leontius. At that time, even reunification with the Church Abroad could not have been ruled out, because the heightened East-West opposition had drawn the émigrés closer together. [14] The situation of the Church Abroad in HK (1950) pp. 24-25. The hierarchs of the Church Abroad, such as Archbishops Vitalis and Tikhon, held memorial services for the departed Metropolitan Theophilus; after moving to the United States, Metropolitan Anastasius visited Metropolitan Leontius. The Synod side proposed that the relationship between both Churches be formed “without the old strife over canonicity”, that it be conducted in the spirit of “brotherly love in Christ with the goal of reestablishing complete communion.” [15] Prav. Rus’ (1951) 6, pp. 3-7.

This remarkable attempt to overcome the schism ultimately failed, however, as a result of the different objectives which both Churches pursued in view of the future. While the Church Abroad understood itself to be part of the whole Russian Church and strove for a restoration of unity after the liberation of the Russian Church from state tutelage, Metropolitan Leontius pursued a separation from the Mother Church with the ultimate goal of autocephaly for American Orthodoxy, which as the heir of the Russian Church had trodden its own path for 150 years. In the 1950s and 1960s, the administrative composition of the Church Abroad took on the form which it still has today. In North America, a total of six dioceses were created by combining already existing dioceses and creating new ones. In 1951, the Diocese of Western America received the Vicariate of Los Angeles, under the direction of Archimandrite Anthony (Sinkevich). In 1962, this vicariate was transformed into an independent diocese. Therefore, Western America received the Vicariate of Seattle, under the direction of Bishop Nectarius (Kontsevich). The Vicariate of Syracuse and Holy Trinity, under the direction of Bishop Abercius, became independent in 1967. The Dioceses of Chicago and Cleveland and Detroit and Flint were joined together in 1957, following after the deaths of both their ruling bishops. They thus became a single diocese – that of Chicago and Detroit in 1957, whose ruling bishop was thereafter Seraphim (Ivanov). In 1974, Bishop Alypius (Gamanovich) was assigned as his vicar. After the death of Archbishop Vitalis (Maximenko) in 1960, Metropolitan Anastasius assumed the title of Metropolitan of Eastern America and New York. Since 1967, the diocese has borne the official designation of Eastern America and New York. Over the years, there have always been two vicariates which bore various titles (Rockland, Washington and Florida, Boston, Manhattan, and Erie). In Canada, the Dioceses of Edmonton and Western Canada and of Montreal and Eastern Canada were joined together. Bishop Vitalis (Ustinov), from 1957 Archbishop and from 1986 Metropolitan, ruled this combined diocese. In South America, the Diocese of Santiago and Chile was created, under the rule of Bishop Leontius (Philippovich).

After he, then Archbishop, was charged with the administration of Argentina and Paraguay, Chile was joined to the latter diocese. Since 1971, the Diocese of Chile has again existed as a separate diocese under the administration of Archimandrite Benjamin (Vosnyuk). The Diocese of Argentina was created in 1948, and since the 1970s has also included communities in Paraguay and Uruguay. From 1955, it was ruled by Archbishop Athanasius (Martos), and after his repose in 1983, by Bishop Innocent (Petrov). The Diocese of Caracas and Venezuela was ruled from 1957 by Bishop Seraphim (Svezhersky), now retired. Brazil became a diocese in 1943, and was ruled by Archbishop Theodosius (Samoilovich) until 1968; he was followed by Bishop Nicander (Paderin), who reposed in 1987. Australia became a diocese in 1946, with two vicariates – Melbourne (1950-1970) and Brisbane (1964-1977). In Europe, the dioceses of Geneva and Western Europe, Berlin and Germany, Vienna and Austria, and Richmond and Great Britain, continued to exist.

From 1945 to 1981, the following bishops were consecrated: Agapitus (Kryzhanovsky, 1957), Alexander (Lovchy, 1945), Alypius (Gamanovich, 1974), Andrew (Rymarenko, 1968), Anthony (Bartoshevich, 1957), Anthony (Medvedev, 1956), Anthony (Sinkevich, 1951), Abercius (Taushev, 1953), Constantine (Yessensky, 1967), Daniel (Alexandrov, 1988), Gregory (Grabbe, 1978), Hilarion (Kapral, 1984), Innocent (Petrov, 1983), Jacob (Thomps, 1951), Jacob (Akkerschijk, 1965), John (Kovalevsky, 1964), Laurus (Skurla, 1967), Leontius (Bartoshevich, 1950), Mark (Arndt, 1980), Nathaniel (Lvov, 1946), Nectarius (Kontsevich, 1962), Nicodemus (Nagaev, 1954), Nikon (Rklitsky, 1948), Paul (Pavlov, 1967), Sabbas (Raevsky, 1945), Sabbas (Sarachevich, 1958), Seraphim (Ivanov, 1947), Seraphim (Svezhevsky, 1957), Theodosius (Putilin, 1969), and Vitalis (Ustinov, 1951). Also, Archimandrite Philaret has consecrated Bishop of Brisbane in 1963, having just emigrated from China in 1962. Metropolitan Anastasius proposed him, as the youngest hierarch, to be his successor in 1964 after the election of a new First Hierarch was locked in a tie between Archbishops Nikon and John. In 1941, Archbishop Philotheus (Narko) was consecrated Bishop of Slutsk, and in 1942 Archbishop Athanasius (Martos) was consecrated Bishop of Vitebsk, by the Belorussian Autonomous Orthodox Church. Both joined the Church Abroad at the Council of Bishops in Munich in 1946.

Over the years, just as in the case of the bishops, there was a change of generations in the clergy. In the ’60s it became necessary to replace many of the refugee clergy, who had died or were too old to serve. Already at the Councils of Bishops in the 1950s, the problem of the gradually developing shortage of priests was given more attention. [16] Ibid. (1953) 19, pp. 4-8; 20, pp. 3-6; 21, pp. 11-12; (1956) 21, p. 5; (1959) 24, pp. 10-11. For example, in the Australian Diocese in 1952, there were 24 priests – 4 between 70-80 years of age, 4 between 60-70, 11 between 50-60, 4 between 40-50 and one under 40 years old. Practically speaking, this aging meant that in the next 10-15 years half of the priests would have to be replaced by younger candidates. [17] Ibid. (1952) 13, pp. 8-9. The situation was similar in other dioceses. Around 1970 in Germany, 80% of the clergy were over 50 years of age. [18] Seide, Die Russisch Orthodoxe Kirche in BRD, p. 169. The contention that the education of priests “is not simple” [19] The situation of the Church in Exile in the realm of Western culture, in Ostkirchliche Informationsdienst (1964) 12, pp. 10-11. can only apply to those dioceses outside of America. While in America, thanks to Holy Trinity Seminary in Jordanville, the problem with regard to priests has not been as acute; however, outside the United States and Canada, there were great shortages in some places. The Council of Bishops in 1959 appealed to all parish clergymen to encourage their parish youth to enter Holy Trinity Seminary. The Council also said that pastoral courses should be offered as well as preparatory courses for reception into the seminary in the dioceses. The Synod formed an academic committee, whose task it was to prepare a program of instruction for such courses and to coordinate the work in this area. [20] Prav. Rus´ (1959) 24, pp. 10-11.

From the 1970s, Holy Trinity Seminary in Jordanville has registered a growing number of students. While, for example, in 1967 only 6 new students entered the seminary, in 1976 there were 14 new students, and in the 1980 academic year, there were even 25 new students. [21] Cf. Part IV, Chap. 4. By the mid-1970s, over 100 priests were educated, including 2 bishops, many hegumens, archimandrites and over 20 hieromonks (another of whom has in the 1980s become a bishop). Of the over 300 clergymen of the Church Abroad, easily half have received their education at Holy Trinity Seminary. One should not overlook the fact that many of the graduates have not taken up the priesthood. Of eight candidates who graduated from the seminary in 1980, only one became a priest. Many candidates cannot make the decision to become a priest in view of the difficult material circumstances in which the families of priests find themselves. Only in a few countries do the clergy receive supplemental financial support from government and church agencies. Only the larger communities can pay their priests enough, though even such priests must subsist on very modest means. In view of the over-emphasis on everything material in our society, it is understandable that younger people find it hard to make the decision to forego many comforts, which the majority of their fellow countrymen take for granted as a part of their everyday life. While in the United States and Canada almost all communities have their own clergyman; in other countries, the priests have more than one community in their care: of the 34 communities in Germany, only 20 have their own priests; of the 4 in Austria, only one; the parishes in Argentina and Paraguay are cared for by 3 archpriests, 2 priests, and 3 deacons; and in Australia-New Zealand, there is only one priest for every other community. [22] Spisok (1981). Added to the general problem of providing parishes with priests is the special problem of language, which became acute in the 1970s. The candidates for the priesthood today have for the most part been born in the West, or at least have grown up there.

Despite all the Church’s care in preserving its traditions and its efforts in maintaining the Russian language and culture, one cannot close one’s eyes to the fact that these young people communicate better in the language of their country than in their mother tongue. Thus, for example, the pupils at St. Sergius High School in New York (opened in 1958 and closed by the Synod in 1985-6) spoke fluent Russian, yet almost without exception spoke English among themselves. There are several places where pupils receive a good part of their education in Russian to this day – the high school in San Francisco and both orphanages for girls in Bethany and Santiago. All other émigré children can only learn the language of their fathers and forefathers in the parish schools (“Saturday schools,” often catechetic) because in many of the post-War émigré families they learned only colloquial Russian. Meanwhile, however, a new generation has been growing up, who have started their own families, in which one often finds that one spouse is not Russian. Thus, many communities within the Church Abroad lost their pure Russian character years ago. Wherever priests find themselves in this situation, they say a part of the liturgy also in the language of the country or serve the liturgy in that language at regular intervals. When considering this issue of multi-nationality, one must also not forget that non-Russian Orthodox émigrés have often joined the Russian Church Abroad. The 1978 Council of Bishops made reference was the first time this apparent change was acknowledged. [23] Orthodox Life (1983) 6, pp. 27-28. In part, this transformation to multi-nationality was also a result of the missionary work of the Church Abroad, because in many countries non-Russian Orthodox communities were formed side by side with Russian ones, whose existence can be traced back to the Church Abroad.

The gradual transformation to accommodate other nationalities can be seen clearly, for example, in the monasteries. Up until the present time, the Russian language has remained the colloquial language in the monasteries, and the liturgy is still celebrated in Church Slavonic; yet of 100 monks now living in monasteries, there are 10 Greeks, 20 Americans, 5 Englishmen and several of other nationalities, and of some 2000 nuns more than two-thirds are non-Russians. [24] Cf. Part IV, Chap. 6. In Holy Trinity Monastery in Jordanville, there have been regular English language services, and half of the monks speak English better than Russian. This is indeed a missionary success, of which the Church Abroad can be proud, yet it fills many of their clergy with sadness, in that it is a sign of their long exile from their homeland.

In close connection with this development is the existence of church schools, the establishment of which intensified from the beginning of the 1950s. While the schools in the refugee camps had had the task of enabling the pupils to obtain a diploma, the parish community school is, in addition to strengthening the Faith, supposed to deepen the consciousness and knowledge of Russian national culture among the émigré children. Except for those within the Church, there are no Russian national schools outside the Soviet Union, other than those schools attached to the Soviet embassies and missions, which are only attended by those from Socialist countries. Almost all Councils of Bishops and the Third Pan-Diaspora Council in 1974 passed resolutions on the strengthening and building up of the Faith among the youth. [25] Cf. Part IV, Chap. 5. The same 100 parish schools which exist today were almost all founded at the beginning of the 1950s. For the older émigrés, the Church was not only a religious center, but also a center for meeting one another. Parishes endeavored to build parish halls, libraries, and reading rooms, in order to give their members the possibility of meeting with others of like mind and establishing small libraries to provide them with books and literature in their mother tongue. This was especially important because outside of these parish libraries there was no possibility for the émigrés to obtain Russian literature. The Church printing presses published historical, literary, and other writings in addition to religious literature. The churches and parish centers were for many of the faithful a part of their old homeland, where they could converse with their fellow countrymen in their native tongue, and keep the customs and traditions of their homeland. Music and dance ensembles, theatre groups and craft groups were formed in many communities. Their members met in the Church-owned buildings for various events. Thus, the parishes had a far-reaching significance for many Russians beyond that of religious care. This is also a reason that the parish members were prepared to support their churches and community centers with generous financial means. In the mid-1950s, after the greatest necessity of the first years was overcome and the material situation of most families gradually improved, there was a church building boom. Of some 150 churches today which were built in the Russian style, the majority were built after 1945. Besides the parish churches, most of the cathedrals were built in these years, including the cathedrals in Los Angeles, San Francisco, Chicago, Montreal, Caracas, Salzburg, Hamburg, and many others. The largest new building of these years was the Cathedral of the Mother of God, the Joy of All Who Sorrow in San Francisco, California. [26] Cf. the pictures in Russ. Prav. Ts., 1, pp. 664-665; Part IV, Chap. 6. In their epistles to the faithful, in particular in their paschal and Christmas messages, the Synod and the Church leadership, the Council of Bishops and the diocesan bishops, referred to the responsibility of each individual believer to contribute to the strengthening of church life. Much attention was devoted to the inner mission, the strengthening of the Faith among their flock. Again and again, the Church leadership stressed the freedom of the émigrés and the Church Abroad and pointed out the responsibility resulting from this freedom for their brothers and sisters in the homeland. The Councils of Bishops discussed the plight of the faithful and the Mother Church in the homeland at every meeting. They turned to the Sister churches and the non-Orthodox churches with appeals, in which they brought to the latters’ attention the persecution of the Church and religion in the Soviet Union. When the reception of the Russian Patriarchal Church into the World Council of Churches in 1961 was under debate, the Church Abroad’s leadership sent a letter to the Conference of Churches in New Delhi and emphasized the dangers that might arise for the ecumenical movement, from the reception of the Patriarchal Church. They emphasized in their letter that the Patriarchal Church had hitherto opposed the ecumenical movement most vehemently. If they were now changing their stance, it was at the command of the government, which was thereby pursuing its own political aims. The Soviet government wanted to deceive the world into believing that freedom of religion existed in the Soviet Union and that the Church possessed the freedom to decide if they would like to join the movement. This, however, was not the case, because simultaneously a new wave of persecution against the Church and the faithful had begun in the Soviet Union, from which the Soviets hoped to divert the attention of the Free World. In 1959, as the new persecution of the Church was initiated, the Council of Bishops turned to the Free World with an appeal to keep their eyes open to the “true situation” of the Church in the Soviet Union. This appeal, like so many other appeals in which the Church Abroad interceded for the faithful in the Soviet Union, went unheeded in most Western countries. [27] Prav. Rus’ (1959) 21, pp. 4-9. Despite the appeals issued by the Church leadership, between 1959 and 1961 alone, 8,500 churches were closed in the Soviet Union [28] Chrysostomus, Kirchengeschichte 3, p. 252. without the full extent of the new persecution even being acknowledged in the West.

A notable act of ecclesiastical autonomy was the canonization of St. John of Kronstadt. The 1964 Council of Bishops, at which the new First Hierarch Metropolitan Philaret was elected, resolved upon this. The preparations for this canonization began in 1953 and it was carried out in 1964, in view of the righteous life which John of Kronstadt had led. [29]Russ. Prav. Ts. 1:366-371; Prav. Rus´ (1953) 12, p. 14; 18, pp. 1-2; 23, pp. 7-10; 24, p. 15; HK (1953/54) pp. 363-364; Prav. Rus´ (1964) 11: pp. 4-9; 12: pp. 1-2; 18 (the entire issue); Der … Continue reading The great significance of this step can be seen in the fact that since 1918 the Russian Church had not canonized anyone. In July of 1918, the canonization of St. Sophronius of Irkutsk was the last time a Russian saint had been canonized. [30] Tal’berg, Istoria Russkoi Tserkvi, p. 853. The Church in the homeland could not risk such a step because of State policy, which was particularly directed against the relics and veneration of saints. Thus, the Church Abroad decided to take the first step in this direction. The last canonizations had all taken place before the Russian Revolution: In 1903, St. Seraphim of Sarov, in 1911 Joasaph, Bishop of Belgorod, in 1913 Hermogenes, Patriarch of Moscow, in 1914 Pitirim, Bishop of Tambov, and finally in 1916 John, Metropolitan of Tobolsk were all solemnly glorified as saints. [31] Ibid., p. 853.

The Patriarchal Church has never officially recognized the canonization of St. John of Kronstadt, nor can such a recognition take place, for to do so would mean that the Patriarchal Church recognized the Church Abroad’s spiritual authority to act on behalf of the Russian Church. Also, the canonization of St. John of Kronstadt would certainly have been unacceptable to the Patriarchal Church, since he had been chaplain to the Imperial Family and had had close contacts with the ruling dynasty. [Trans. note: He had also prophesied the Revolution and its dire aftermath.] The Patriarchate protested against this canonization by the Church Abroad, without, however, denying the sanctity of the new saint.

After the Metropolia received autocephaly, the new Church resolved to canonize Herman of Alaska; the Church Abroad denied that the former had the right to take this step, but did not question the sanctity of Herman. But in view of the great veneration in which the latter was held by many of the Church Abroad’s faithful in North America, the Synod of Bishops resolved to conduct a simultaneous canonization of Herman of Alaska, who thereby became the first Orthodox saint to live and die in North America. Since then, he has been recognized as a saint by the Church Abroad, the Orthodox Church in America, and the Patriarchal Church, but not by the Paris Jurisdiction, because the Patriarch of Constantinople did not recognize the Metropolia’s autocephaly. [32] Der christl. Osten (1970) 4-5, p. 138; Prav. Rus‘ (1970) 14, pp. 1-4; 15, p. 3; 16, pp. 3-5. At the Council of Bishops in 1978, the Church Abroad glorified Blessed Xenia of Petersburg among the ranks of Russian saints. The Church Abroad ascertained that the new saint was also venerated greatly by the faithful in the Soviet Union; this was confirmed by a 1962 atheist brochure. In this brochure entitled “The Truth about Petersburg’s Holy Shrines,” it says, Of all of the pilgrimage sites to which the faithful had streamed even in Tsarist Petersburg, the Chapel of Blessed Xenia attracts the greatest number of pilgrims from the city and neighboring areas… Here, the divine services are often held and visitors flock to them. The candles burn in great numbers, clouds of incense rise, church singing resounds. Numerous people attending the service put many slips of paper on the grave, on which various requests are inscribed.

Naturally, the author of this brochure also has an explanation at hand for these occurrences: “Perhaps the cult of this shrine would, like so many others, long ago have disappeared. But to keep up this fairy-tale, the servants of the cult, who live in revelry and riot, propagate Blessed Xenia in every way possible. Thus it is not surprising if the clergy fill the faithful with all possible ‘miracles.” [33] Quoted from the Information Service of Glaube in der zweiten Welt, 28 Nov. 1978, pp. 15-16. Meanwhile, the chapel at the Smolensk Cemetery was walled up and an oversized bust of Lenin sculpted within it. [Trans. note: Shortly after completion, the bust of Lenin was defaced. In 1987, the chapel was reopened and cleaned up; the walls were structurally restored and painted. This took place in anticipation of the Millennium of Rus’ and, it may be assumed, with the expectation of an influx of tourists and pilgrims from the West.] Both the presentation in the atheist brochures and the measures taken by the State since the canonization, give the Church Abroad through this glorification the right to act upon the mood and ideas of the Russian Christians in the homeland.

The glorification of the New Martyrs took place at the Council of Bishops in 1981, at which all the victims and witnesses of the Faith, who were martyred during the Russian Revolution, the Civil War and the Communist persecution, were canonized, including the Imperial Family, Patriarch Tikhon, the bishops, priests, monks, nuns, and laity. The canonization of these “new martyrs and confessors” had been discussed since the 1930s. In Brussels there had been a church dedicated to them for years. In many Russian churches and émigré homes there is an icon depicting “All Saints of Russia,” whose feast was introduced for the first time by the Moscow Council in 1917. Some time ago, Archimandrite Cyprian painted a large triptych icon of this feast, the middle section of which measures 400 x 250 cm. On this icon [34] Cf. the photographs in Russ. Prav. Ts., 1, pp. 526-527. are depicted the Russian saints and martyrs, who were canonized by the Russian Church. On the right-wing of this triptych, the martyrs and confessors who were canonized in 1981, are depicted, including the Imperial Family, Patriarch Tikhon, and numerous bishops who lost their lives during their lives at the hands of the Bolsheviks. In a practical way, this wing of the triptych was an anticipation of the long-discussed canonization, which, as we know, was also desired by many in the Soviet Union. In a September 12, 1979 letter, the dissidents Fr. Gleb Yakunin, Basil Fonchenkov, Victor Kapitanchuk, and Leo Regelson petitioned for just such a canonization. Concerning the question of the canonization of the last Tsar and his family, the letter says,

“The Imperial Family occupies an entirely special place among the martyrs of the 20th century. The question of canonization has long been in the consciousness of Orthodox Russians… First one must distinguish between the canonization of the Tsar and that of his family. In our days, we have met no one, even among the atheists, who would defend the execution of the Imperial Children. The purity of their life and death also covers the death of their parents with a saintly crown. That the Tsar and his wife partook of the same martyrdom as their children must be seen as a witness before God that they were chosen. Nicholas II may have been a poor ruler and a sinful Christian, <…> but according to universally recognized teachers of the Church and the rite of canonization itself, the gravest sins and mistakes of church members committed during their life cannot stand in the way of their ecclesiastical glorification. If the question of the canonization of Nicholas II and his wife is to be decided upon, it is appropriate to recall the words from the Epistle to the Hebrews: “Remember them which have the rule over you, who have spoken unto you the word of God: whose faith follow, considering the end of their conversation.” (Heb. 13:7) Their gentleness and the courage with which they met their fate led the imperial pair to the highest plane of Christian activity. The willingness of their sacrifice elicits a feeling of deep respect. Their end as brings to mind unbidden the first princely saints of the Russian land, its heavenly protectors Boris and Gleb… Through God’s dispensation, they were chosen to suffer, no longer having any political power and surrendering any desire to assume this power again. Nicholas II suffered as a victim of the Orthodox Empire, as the bearer of centuries-old ecclesial ideas concerning the power of God on earth… In this fact, that he was found worthy to suffer in this way, we see God’s witness to his sanctity.” [35] Volnoe Slovo (1979) 35-36, pp. 129-138.

This stance taken by Russian Christians in the Soviet Union has been extensively quoted to show, that the Church Abroad’s opinion in this matter was neither extreme nor totally unsupported. Furthermore, Patriarch Tikhon served a memorial service for the Imperial Family when he learned of their murder, and the Church Abroad merely continued serving them on the subsequent anniversaries of their death – a tradition which Patriarch Tikhon had begun and which is normal practice for friends and relatives of the departed. The arguments brought against canonization in the case of the Imperial Family cannot be considered to be in keeping with the thought and traditions of the Church. Furthermore, the canonization must be viewed in connection with the canonization of the many known and unknown witnesses for the Faith, who also lost their lives during the Bolshevik persecution of the Church. The other Orthodox Churches cannot close their eyes to this fact. [36] Prav. Rus’ (1979) 6, p. 8.

Moreover, the canonization of the New Martyrs by the Church Abroad has been welcomed by the Patriarch of Jerusalem. In May of 1982, Patriarch Diodorus received a delegation of the Church Abroad, which consisted of Archbishops Anthony of Geneva, Paul of Sydney, Laurus of Syracuse, and Bishop Gregory of Washington, in the throne room of his residence. The hierarchs were in the Holy Land for the solemn translation of the relics of the New Martyrs, the Grand Duchess Elizabeth and the nun Barbara. Patriarch Diodorus stressed the necessity of the canonization in his address, and said: “Their arrival here is holy, as also the fact of the canonization of the holy New Martyrs is holy because of one like the other concerns those people who have suffered martyrdom for Orthodoxy.”

Furthermore, His Beatitude pointed out that the Church Abroad “for various reasons finds itself outside its homeland, and the Church in Russia provides us with New Martyrs daily, and millions of people follow the examples of the Imperial Martyrs and the holy Martyr, the Grand Duchess Elizabeth.” “And we,” His Beatitude said, “cannot remain indifferent to such an exalted event, as the canonization of the martyrs; their celebration is taking place in territory under our jurisdiction. Therefore, we have resolved to take part in this holy matter by sending a delegation, to bear witness to our Orthodox unity and by this official act to stress its legitimacy.” His Beatitude Diodorus concluded his greeting with the wish “that the blood of the Martyrs, which has been shed, might be sanctified water, which would richly irrigate the timber of Orthodoxy, whereby we may be strengthened in unity and truth through the prayers of all the New Martyrs.” [37] Bote der deutschen Diozese (1982) 3, pp. 4-5.

Patriarch Diodorus’s words contained two extremely important points: first, that the Jerusalem Patriarchate recognizes the right of the Russian Church Abroad to act and speak for the Russian Mother Church in the homeland (the legitimacy of this official act), and secondly, that the Patriarchate of Jerusalem considers the Church Abroad to be its Orthodox Sister Church and proceeds, based on the unity of both Churches, to bear witness to “our Orthodox unity.” The significance of this statement is so very great because the opponents of the Church Abroad have maintained that the Church Abroad is not “recognized” by any other Orthodox Sister Church. This assertion can only be made on the basis of disinformation; its truthfulness is corroborated by the word of Patriarch Diodorus alone.

In 1977, the Patriarchate of Moscow resolved once again to canonize a saint, though this passed “almost unnoticed” by the faithful and by publicity. At the request of the Orthodox Church in America, Metropolitan Innocent (Veniaminov) was glorified as the “Apostle of North America and Siberia.” The OCA simultaneously celebrated his canonization. This canonization has not been recognized by the Church Abroad.

The Church Abroad has also glorified St. Paisius Velichkovsky (1982) and the Optina elders (1990), and has officially begun to collect materials in preparation for the canonization of Archbishop John (Maximovich).

The Church Abroad’s canonizations have been the result of decades of struggle within the Church Abroad to determine its own position and spiritual authority. This development began with the creation of dioceses by the Stavropol Council in 1919. This path was continued outside of Russia as the Church Abroad established its own ecclesiastical organization. The break with the Mother Church which later followed and the lack of recognition of each other’s canonical bases have led to a situation in which both Russian Churches claim to be the Russian Church of Patriarch Tikhon and have grown further and further apart, treading their own separate paths for decades. The canonizations of recent years, and the mutual refusal to recognize the new saints, are the conclusion of the struggle over canonical and spiritual authority between both Churches. Though the continuation of this struggle cannot diminish the merits of these new saints, all Russian Christians, however, are grieved by it. Thus, the authors of the aforementioned letter wrote: “Can it really be that the demands to fulfill the religious duties towards the martyrs, to partake in the paschal joy of their glorification, would not prove to be more important than the differences and conflicts, which in our day so tragically separate the Russian Orthodox Christians?.. For us, because we live in Russia, it is beyond a doubt that the glorification of the saints cannot be a private concern of one of the jurisdictions of the Russian Church. We bear witness to the fact that the veneration of the martyrs and confessors through prayer is becoming more and more widespread in Russia and expresses the deep confidence that the act of canonization, even if it is only to be accomplished by the Synodal Church, will be met with true religious zeal and enthusiasm by the Russian clergy and faithful.”

Since 1945, there have been 20 Councils of Bishops and one Pan-Diaspora Council. Representatives of the clergy and laity took part in the Third Pan-Diaspora Council, which was held at Holy Trinity Monastery. In contrast to the previous two councils (1921 and 1938), no volume about the sessions and resolutions was published. The reports and resolutions were printed in “Orthodox Russia,” “Church Life,” and many other journals of the Church Abroad. All the acts of the last Pan-Diaspora Council are in the Synodal Archives (File 2/72) as well as those of the preparatory sessions (File 4/65 and 1/71). Fourteen bishops, 38 priests, representatives of the diaconate and monastics, and 53 lay people participated in the Council. The focal point of the Council was the development of the Church Abroad and the religious situation in the homeland, as well as the developments of the Patriarchal Church. Alexander Solzhenitsyn, Vladimir Maximov, and Andrew Sinyavsky were questioned about the developments in the homeland. The Patriarchate directed an appeal for reunification to the participants; the Church Abroad for their part appealed to the Paris Jurisdiction and the OCA to overcome the schisms, though the Council did not achieve this end. However, in connection with the Old Believer Schism, the Council lifted the ban that had been imposed upon this group by the Russian Church in 1656 and 1667. With this decision, the Council the Pan-Russia Council of 1917-18, which had recommended the lifting of the ban, but had not brought forth a resolution due to the cessation of the Council sessions in consequence of the political developments. Only a verbal decision was reached.

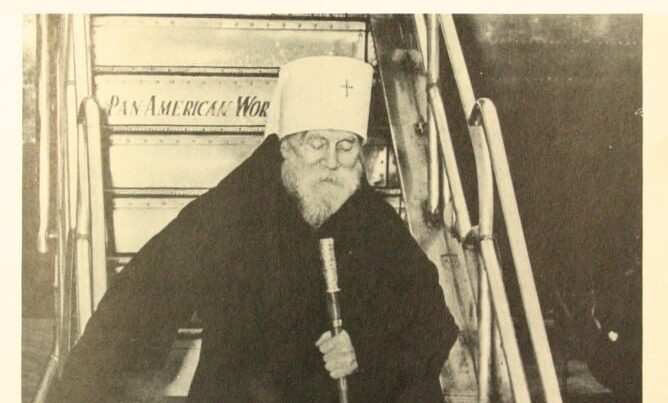

A further event in the life of the Church Abroad of these years was the election of a successor to Metropolitan Anastasius, who retired from his position as First Hierarch of the Church Abroad in 1964 on account of his advanced age. The new First Hierarch was Metropolitan Philaret, who had only been consecrated bishop in 1963. Metropolitan Anastasius had been the First Hierarch for almost thirty years. He was the last hierarch of the Russian emigration to have been consecrated bishop before the Revolution. His main service to the Church consisted of rebuilding the Church Abroad during the difficult post-War years. After its heavy losses, it appeared that the Church Abroad would not recover from these blows. The great respect in which Metropolitan Anastasius was held by many of the old émigrés and the refugees who fled their homeland was, however, more than enough to avert further calamity from the Church Abroad.

The center of ecclesiastical life was transferred overseas to America. Thus, it was only natural that the Church administration be moved there. The consistent stance of the Church leadership towards the Moscow Patriarchate and its uncompromising rejection of Communism also determined the ecclesiastical and political basis of the Church Abroad after 1945. After the administrative reorganization of the Church, the Church’s principal objective was the strengthening of the Faith and the preservation of Russian national culture among the faithful. The Church leadership’s view of itself as the free and independent part of the whole Russian Church, which could act in the name of the Russian Church, acquired a new dimension during the tenure of Metropolitan Anastasius: the preparation for the canonization of John of Kronstadt had been in progress for fifteen years before the 1964 Council of Bishops carried it out. The cooperation between of the old and new First Hierarchs – Metropolitans Anastasius and Philaret – on this canonically significant event also ensured continuity on the path to complete autonomy for the Church Abroad. The restoration of relations between the Patriarchal Church and the other Christian Churches led to the latters’ severing of relations with the Church Abroad, which thereby won a new freedom: they no longer needed to defer relentless exposure of the oppression of the Church and the faithful and were answerable for this criticism to no one but themselves. That the Church Abroad spared neither the leadership of the Patriarchal Church, nor the bishops, nor the priests, who were silent about the real situation of “freedom” of the Church in the Soviet Union, and who denied that any persecution was being waged for religious reasons, was not only natural but was also their duty.

In 1970, the Church Abroad celebrated the 50th anniversary of its establishment. On this occasion, a small commemorative volume was published, which was mainly directed to the remove “the” those who were not members of the Church Abroad, a short synopsis on the Church in Exile entitled The 50th Anniversary of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia (Pamyatka 50-letiya Russkoi Pravoslavnoi Tserkvi Zagranitsei: 1920-1970 [Montreal 1970]). This anniversary volume appeared in a bilingual form, in Russian and English. In 1968, a two-volume work produced under the editorship of Count A.A. Sollogub, entitled Russkaya Pravoslavnaya Tserkov Zagranitsei (Volumes I-II, New York. 1968.) appeared. In this work, following a brief historical introduction, the Church Abroad gives a survey of its dioceses, communities, institutions, and properties in the West. Almost all the parish churches, monasteries, and other properties were pictured. Also, in both these volumes, there are numerous pictures of community life and joint church meetings. This noteworthy work, which unfortunately has not obtained a wide distribution, again reflects the presence of the Church Abroad in the West but says far too little about the achievements the Church had attained for the Russian emigration. Nevertheless, the Church Abroad can rejoice in the fact that neither the Paris Jurisdiction nor the Metropolia in North America can point to such a global representation. The smallest diaspora communities in the farthest corners of the world have been and are cared for by the Church Abroad, which is the only Church outside of Russia from its establishment to the present day to have parishes wherever Russians live. Despite all the hostilities and attempts to question the canonical basis of this Church, it has been the only one among the Russian émigrés to understand how to master the difficult task of guarding and maintaining the Faith of their forefathers.

Though these achievements are not particularly noted in this aforementioned double jubilee album, they are nonetheless apparent in the photographs, which often express more than words. In 1988, the Russian Church celebrated the Millennium of the Baptism of Russia. It was, unfortunately, unthinkable that the Russian Church could celebrate this event as a reunited Church, but it would have been a giant step forward if the emigration had been able to celebrate this anniversary together. If the “canonical disputes” should have proven to be weaker than the thousand-year heritage of the Russian Church, there would then have been the great hope for the future of the Russian Church. A united Church in the emigration, which would speak for all the Russian faithful outside of Russia would possess not only great spiritual authority but also could win back recognition by all of Orthodoxy as a Church on equal footing with the Patriarchal Church.

References

| ↵1 | “Kirche in Nordamerika. Geschichte,” in HK (1949) pp. 135-139; “Lage in Nordamerika” in HK (1954) pp. 140-142. |

|---|---|

| ↵2 | Orthodoxy in America. Some statistics in: ECR (1968) pp. 70-73; Yearbook of American and Canadian Churches (1978), pp. 87, 127. |

| ↵3 | Severnoi Ameriki, p. 210; Spisok (1981) pp. 3-18. |

| ↵4 | Tarazar, p. 302. |

| ↵5 | Spisok (1981) pp. 28-32. |

| ↵6 | Cf. Part IV, Chap. 2; Russ. Prav. Ts. 1, pp. 482-505. |

| ↵7 | Prav. Rus’ (1952) 4, p. 15. |

| ↵8 | The parents of J. Semenenko had been friends of Metropolitan Anastasius from pre-revolutionary times. Their son had become vice president and director of the First National Bank of Boston and had built up considerable assets. He died in May 1980. (Newsletter, 30, May 1980, pp. 1-2). |

| ↵9 | Prav. Rus’ (1958) 3, p. 10; Russ. Prav. Ts. 1:181-198. |

| ↵10 | Tserk. Zhizn´ (1959) 5-6, pp. 65-66; 9-10, pp. 143-144. |

| ↵11 | Russ. Prav. Ts. 1:505-507. |

| ↵12 | Pamyatka 50-letiya, pp. 49-64. |

| ↵13 | Prav. Rus´ (1950) 23-24, p. 29; (1951) 6, p. 3. |

| ↵14 | The situation of the Church Abroad in HK (1950) pp. 24-25. |

| ↵15 | Prav. Rus’ (1951) 6, pp. 3-7. |

| ↵16 | Ibid. (1953) 19, pp. 4-8; 20, pp. 3-6; 21, pp. 11-12; (1956) 21, p. 5; (1959) 24, pp. 10-11. |

| ↵17 | Ibid. (1952) 13, pp. 8-9. |

| ↵18 | Seide, Die Russisch Orthodoxe Kirche in BRD, p. 169. |

| ↵19 | The situation of the Church in Exile in the realm of Western culture, in Ostkirchliche Informationsdienst (1964) 12, pp. 10-11. |

| ↵20 | Prav. Rus´ (1959) 24, pp. 10-11. |

| ↵21 | Cf. Part IV, Chap. 4. |

| ↵22 | Spisok (1981). |

| ↵23 | Orthodox Life (1983) 6, pp. 27-28. |

| ↵24 | Cf. Part IV, Chap. 6. |

| ↵25 | Cf. Part IV, Chap. 5. |

| ↵26 | Cf. the pictures in Russ. Prav. Ts., 1, pp. 664-665; Part IV, Chap. 6. |

| ↵27 | Prav. Rus’ (1959) 21, pp. 4-9. |

| ↵28 | Chrysostomus, Kirchengeschichte 3, p. 252. |

| ↵29 | Russ. Prav. Ts. 1:366-371; Prav. Rus´ (1953) 12, p. 14; 18, pp. 1-2; 23, pp. 7-10; 24, p. 15; HK (1953/54) pp. 363-364; Prav. Rus´ (1964) 11: pp. 4-9; 12: pp. 1-2; 18 (the entire issue); Der christliche Osten (1964) 3, p. 72. |

| ↵30 | Tal’berg, Istoria Russkoi Tserkvi, p. 853. |

| ↵31 | Ibid., p. 853. |

| ↵32 | Der christl. Osten (1970) 4-5, p. 138; Prav. Rus‘ (1970) 14, pp. 1-4; 15, p. 3; 16, pp. 3-5. |

| ↵33 | Quoted from the Information Service of Glaube in der zweiten Welt, 28 Nov. 1978, pp. 15-16. |

| ↵34 | Cf. the photographs in Russ. Prav. Ts., 1, pp. 526-527. |

| ↵35 | Volnoe Slovo (1979) 35-36, pp. 129-138. |

| ↵36 | Prav. Rus’ (1979) 6, p. 8. |

| ↵37 | Bote der deutschen Diozese (1982) 3, pp. 4-5. |