Part IV, Chapter 1.2

The Communities in Eastern Europe

The collapse of Imperial Russia in 1917-18 led to the national independence of the western fringe of the Russian Empire: Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland became independent republics. The resurrected Polish state and the newly-founded kingdom of Romania used the weaknesses of the Soviet state to expand their eastern borders. In Finland, the Baltic States, Poland, and Czechoslovakia lived millions of Orthodox faithful, who before 1918 had belonged to the Church of Russia: Orthodox Russians, Belorussians, and Ukrainians, Finns, Estonians, Latvians, Lithuanians, Poles, Romanians, and numerous small national minorities.

Except for Romania, which annexed the territory between the Pruth and Dniester Rivers (Bessarabia and Moldavia), the Orthodox formed a religious minority in all other countries, though in Poland it was a noticeably large group. In Poland between the Wars, five to six million Orthodox lived.

The establishment of a national Orthodox Church in this country beginning in 1921 and the granting of autonomous or autocephalous status should have been accomplished according to Orthodox Canon Law by the Russian Mother Church, from which the missionary Church originated. The people of these countries, who were fighting for their national recognition and identity, were anti-Russian in sentiment after 1918. Added to their national (anti-Russian) inclination was also a political element: the rejection of the Communist Soviet government. For the Russian Church-oriented Orthodox faithful, this meant a double separation from their Mother Church. The government prevented the faithful from having contact with the Patriarchal Church; the Soviet government prevented the Patriarchal Church for their part from caring for their faithful abroad.

The most simple and canonically unimpeachable solution to the problem would have been for the Orthodox leadership in these countries to have handed over the leadership to the Russian bishops there who had received consecration by the Russian Mother Church until normal relations could be reestablished with the Patriarchal Church. Archbishop Seraphim (Lukianov) lived in Finland; Archbishops John (Pommer) and Eleutherius (Bogoyavlensky) were in the Baltics; Archbishop Panteleimon (Rozhnovsky) and the Bishops Sergius (Korolev) and Vladimir (Tikhonitsky) resided in Poland. In the emigration, there were also other bishops whose divided dioceses lay in part in the new countries: Metropolitans Anthony and Platon, and Archbishops Eulogius and Anastasius. All these hierarchs could raise legitimate claims to the care of the Orthodox in these lands.

Because Romania was a special case, i.e., an Orthodox national Church already existed, it could care for the Orthodox in annexed Bessarabia, even if this had originally been part of the Russian Church. With the exception of Estonia, the local national Orthodox groups comprised a minority.

In Finland there lived 500,000 Orthodox, including only 50,000 Finns; in Estonia, there were 212,764 (in 1934) Orthodox − 118,000 Estonians and 92,000 Russians; in Latvia (1935) lived 174,389 Orthodox and 107,195 Old Believers, of which 210,633 were Russians; in Poland, there were 5-6 million Orthodox (largely Belorussian and Ukrainians), of whom only 400,000 were Poles. [1] Dubanaitis, pp.153-154; Laatsi, pp. 63-73; Kahle, pp. 89-107. Jahrbuch der Orthodoxie 1976/77, pp. 37-38, 158-160, 163-164. Nonetheless, after 1918, suppression of the Russian influence also set in on church life, which found its parallel in the political, cultural, and economic realm.

The goal of these strivings was the establishment of national Orthodox Churches, which would be independent of the Russian Church. This nationalization was distinguished before all else by two things: the introduction of the local language into the divine services and the introduction of the New Calendar (the Julian Calendar, which is still used today in the Russian Church, is 13 days behind the Gregorian). The Russian minorities opposed these reforms in these countries. Thus, for example, numerous monks and nuns left the monasteries which had once belonged to the Russian Church in Bessarabia and Finland (Valaam and Konevets) and joined the Church Abroad, after these adherents of the Old Style (the Old Calendarists) were persecuted as “schismatics” and “sectarians.” [2] Prav Rus´ (1938) 1, p. 2. In Poland during the time between the Wars, there was even official persecution of Orthodoxy. With the consent of the government, the Roman Catholic Church confiscated a part of the property of the Orthodox Church. Churches, monasteries, and other institutions were turned into Roman Catholic property. [3]On the situation of Orthodoxy in Poland between the wars, see Lissek, Orthodoxe Kirche in Polen; Verdernikov, Delo polskoi tserkvi; Zheleznyakovich, K istorii… v Polshe; Popov, Gonenie… v … Continue reading The nationalist, anti-Russian stance of the governments of these countries also prevented these communities − even the purely Russian ones − from joining the Karlovtsy Synod of Bishops. The ruling Russian bishops in these countries, after entering into conflicts with the various opponents striving for the autonomy of the national Churches, were hindered from exercising their office and ultimately banished from these dioceses and countries.

The national Orthodox groups’ strivings for independence were not only supported by their respective governments, but also by the Œcumenical Patriarchate, which held out the prospect of autonomy and autocephaly. The Estonian Orthodox Church took the lead in 1921, with its some 118,000 Orthodox Estonian members. The Diocese of Tallinn was set up by them under the direction of Bishop Alexander (Paulus, later Metropolitan). After that, the Orthodox Estonians, as the Estonian Autonomous Orthodox Church, subordinated themselves to the Œcumenical Patriarchate. In that country, there were 164 clergymen, including 3 bishops, 138 priests, and 23 deacons. [4] Cf. Part V; Dubnaitis, p. 153. There was also a convent with a skete and podvorye [metochion, dependency] (the Dormition Convent in Pukhtitsa), in which over a hundred nuns lived. [5] K. Soop, & U. Keskkjula, Kuremyaevsky monastyr’; Zybkovets, p. 127. After the Soviet annexation of Estonia, “the Estonian Schism” came to an end through the reunification of these communities with the Patriarchal Church. The Diocese of Tallinn and Estonia has existed since that time. [6] JMP (1945) 4, pp. 3-6.

In Latvia, developments occurred very much the same as in Estonia. With the support of the Latvian government, a local council met in 1920, at which the Latvian Church decided to be independent of the Russian Church. Archbishop John (Pommer) of Riga and Latvia became its head. The majority of the faithful there were Russians (some 210,000 Orthodox and Old Believers compared with 71,000 Latvians). [7] Dubnaitis, p. 154. For this reason, autonomy was more difficult to realize there than in Estonia. The Orthodox and the Old Believers had 165 churches and 130 clergymen, a theological seminary in Riga, and a monastery (St. Alexis) and convent (Holy Trinity), in which 200 monks and nuns lived. [8] Zybkovets, p. 127.

Archbishop John (Pommer) [9] Cf. Part I, Chap. 3, note 30. was essentially closer to the Church Abroad after the schism, than to the jurisdiction of metropolitan Eulogius; but the latter had many supporters among the laity and the lesser clergy. Thus, for example, Archbishop John forbade the Christian Student Union, which had a close spiritual connection to Metropolitan Eulogius’ jurisdiction, from conducting any activities in those communities under his direction. This led to divisions within the communities. The Archbishop also opposed Latvian autonomy. In 1934, he was murdered; the case was never solved. [10]Balevic, p. 13 − This work by Balevic explains the development of the Latvian Church. Despite its Marxist Soviet standpoint, it includes important facts on the history of Orthodoxy in Latvia. Cf. … Continue reading

After his death, the advocates of Latvian autonomy achieved their aim with the support of the government and established the Latvian Orthodox Church, which declared itself “Autocephalous.” The First Hierarch was Bishop Augustine (Augustine Peterson, until 1936 archpriest, after 1940 Metropolitan). He joined the Œcumenical Patriarchate. [11] Balevic, pp. 14-15. The Russian émigrés living in the country welcomed this step in so far as it meant a final break with the Moscow Patriarchate, which the majority of the faithful rejected after Metropolitan Sergius’ Declaration.

After the Soviet invasion in 1940, the Orthodox were “reunited” with the Patriarchal Church. On April 11, 1941, Metropolitan Augustine signed a protocol in Moscow on the dissolution of the Latvian Church, which was to join the Patriarchate. The latter, in turn, designated Metropolitan Sergius (Voskresensky) as Exarch for the Orthodox in the Baltics. Metropolitan Augustine was supposed to retain the leadership of the Latvian Orthodox, but he requested permission to retire. In 1944, the Metropolitan was evacuated to Germany, and from 1946, he maintained communion with the Church Abroad. After his death in 1955, he entrusted his small flock to the Church Abroad. [12] Prav. Rus’ (1955) 21, p. 12; “The Orthodox Church Under German Occupation” in Eastern Churches Review (1974) pp. 131-161.

The preconditions for the autonomy or autocephaly of a Church were most favorable in Poland, where 5-6 million faithful lived and where a few hundred churches were cared for by priests and bishops. The Russian bishops living there remained canonically faithful to their Mother Church and were decisive opponents of the strivings for autocephaly, which the Polish Orthodox minority propagated and demanded of the government and which resulted in a weakening of the Orthodox Church. After the expulsion of Bishops Sergius and Vladimir, Archbishop Panteleimon was retired and lived in the Zhirovitsy Monastery of the Dormition. [13] Metropolitan Vladimir, pp. 156-157: on the biography of Metropolitan Panteleimon.

In 1925, the Orthodox there finally received an independent Church. The Œcumenical Patriarchate granted them autocephaly: the Russian Church did not recognize the Polish Orthodox Autocephalous Church. In 1948, under changed political circumstances, the Patriarchate recognized the autocephaly of the Polish Church, whereas the Church Abroad rejected it. Today, some 500,000 faithful belong to the Church, which is organized into four dioceses and has a Theological Faculty and two small monasteries. [14] Jahrbuch der Orthodoxie 1976/77, pp. 158-162. During World War II, the First Hierarch of the Polish Orthodox Church, Metropolitan Dionysius (Valedinsky), gave his consent to the formation of autonomous Belorussian and Ukrainian Churches. The Polish Orthodox Church lost over 80% of its faithful thereby. The bishops, clergy, and faithful of both these churches were united in the emigration with the Church Abroad. [15] On the history of the Ukrainian and Belorussian Autonomous Orthodox Churches, cf. Part I, Chap. 6, p. 75f.

In Finland, there had been a Russian Diocese since 1892. After the Finnish Declaration of Independence, the independence of Finnish Orthodoxy was established by constitutional law in 1918. This one-sided declaration of independence was not recognized by any other Church; it was condemned decisively by the Russian Church, for whom Archbishop Seraphim (Lukianov) remained the rightful head of the Church of Finland. The Ecumenical Patriarchate supported the struggle for independence, by granting the Finnish Orthodox Church autonomy in 1923. Bishop Herman (Aav) became the First Hierarch; he had been consecrated by the Estonian Archbishop Alexander (Paulus). The Russian Church considered this consecration to be uncanonical and declared the appointment of Bishop Herman as the First Hierarch of the Orthodox communities in Finland as invalid. [16] Glubokovsky, Voina i mir; Zheleznyakovich, Finlandskaya tserkov’; Tserkovnye Vedomosti (1924) 19-20, p. 6. The Finnish authorities reacted to this condemnation by exiling Bishop Seraphim, who had been elevated to archbishop for his faithfulness to the Mother Church. When the New Calendar was introduced into the Orthodox Church of Finland in 1925, many communities were split. The advocates of the Old Calendar were often also advocates of the jurisdictional membership in the Russian Church and, therefore, separated themselves from their parishes. Wherever they succeeded in establishing their own communities, e.g. in Helsingfors and Vyborg, they maintained contacts with the Russian Church. In any case, these communities were again divided because in their midst were supporters of the Patriarchal Church, the Church Abroad, and the Paris Jurisdiction. [17]Prav. Rus’ (1937) 11, p. 5. From 1945 there were parishes in Vyborg and Helsingfors, which belonged to the Patriarchal Church: JMP (1945) 11, pp. 5-13; (1953) 9, pp. 7-18; (1959) 1, pp. 60-63; … Continue reading

After the cession of Karelia to the Soviet Union in 1939/1944, the Finnish Orthodox Church lost some 90% of its property, including the ancient Russian monasteries on the islands in Lake Ladoga (Valaam and Konevets). The government gave support to the intensive rebuilding work of the approximately 60,000 faithful remainings. Since 1969, there have been attempts in progress to obtain autocephaly.

Whereas, according to the opinion of the Russian Church, the jurisdictional authority over the Orthodox communities in the aforementioned countries was rightful that of the Russian Church, the canonical situation in the countries of southeastern Europe was clear cut. According to Orthodox canon law, all Orthodox faithful − irrespective of nationality − on the territory of an Orthodox Church belongs to the local Church. This principle was also never violated.

The jurisdictional competence outside the territory of autocephalous Churches, is, however, contested, and upon it Constantinople laid claims. [18] Cf. Part I, Chap. 4. The Church Abroad’s experts on canon law have not questioned Orthodox canon law in the instance of the territories of Local Orthodox Churches, where Russian refugee communities were located. The extensive autonomous administration of the Russian communities in Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, Greece, Turkey, North Africa (the legal jurisdiction of the Patriarch of Alexandria), and also Czechoslovakia [19]In Czechoslovakia after 1922 there was a small Czech Orthodox Church under the leadership of a former Catholic, Bishop Gorazd (Pavlik), to which 1,000 faithful belonged. This Church was under the … Continue reading can be explained by “canonical hospitality,” as well is also acknowledged in the 39th Canon of the Sixth Œcumenical Council. The refugees’ establishment of parallel jurisdictions in many of these countries can only be explained by “the law of love,” i.e., the goodwill of individual national Churches. [20] Grabbe, Tserkov’ i uchenie 1, pp. 267-268. Thus, it is also essentially irrelevant to consider whether in the Orthodox countries of southeastern Europe Russians had their own dioceses or the communities belonged to the Local Church.

In Romania, this question simply did not arise because, with the exception of the Russian embassy church in Bucharest, all other Russian refugee churches belonged to the Romanian Orthodox Church, and the refugees did not have their own ecclesiastical administration there.

The Bucharest parish was under the authority of Metropolitan Eulogius. [21] Nikon, Zhizneopisanie 7, p. 234. Czechoslovakia was not an Orthodox country. During the time between the Wars, most of the Orthodox in eastern Slovakia (Carpatho-Russia/Carpatho-Ukraine) belonged to the Serbian Orthodox Church, which had set up its own diocese in Preshov-Mukachevo. Those Church Abroad communities located in Czechoslovakia had the same status as the Russian communities in Yugoslavia. [22]After the Soviet annexation of this territory, the Serbian Church relinquished its diocese, which in turn became part of the Russian Church. Russie et Chretiente (1947) pp. 89-90; JMP (1945) 11, pp. … Continue reading

In Turkey, Bulgaria, Yugoslavia, and Greece, the Russian refugee communities were granted an autonomous ecclesiastical administration by the primates of the Local Orthodox Churches. They gave a Russian bishop jurisdiction over these communities and even permitted them to set up diocesan councils to support the bishop in his administration. This resulted in de facto Russian dioceses because all of the prerequisites for such existed. The Œcumenical Patriarch initiated this with Decree No. 9084, dated 22 December 1920, which gave the Russian bishops full authority to rule their ecclesiastical and religious affairs independently. The Patriarch, however, reserved the right to oversee and make decisions concerning martial law. [23] D´Herbigny/Deubner, Evêques Russes, p. 16. Archbishop Anastasius was given the right to care for the 20 or so communities in close proximity to Constantinople and the ten communities on the island of Lemnos and in Gallipoli, where large numbers of refugees lived at that time. [24] Nikon, Zhizneopisanie 5, pp. 6-11. In August of 1921, Bishop Seraphim (Sobolev) was assigned to oversee the Russian communities in Yugoslavia. [25] D´Herbigny/Deubner, Eveques Russes, p. 18; Tserk. Ved. (1922) 2, p. 9; Ibid. 3, pp. 7-8. In the autumn of 1921, the Supreme Ecclesiastical Administration directed an inquiry to the Archbishop of Athens with the request for his consent to allowing the administration of the Russian communities in Greece to be transferred to a Russian bishop. The archbishop clearly recognized the “right to a self-administered diocese” in his answer to the Russian communities. Bishop Hermogenes (Maximov) assumed this task, which also included the Russian communities on Cyprus and in Egypt, with the exception of the military communities, which remained under the care of Bishop Benjamin (Fedchenko). [26] Ibid., 11-12, p. 12. Thus, by the end of 1921, there existed de facto Russian dioceses in Constantinople (Turkey), Bulgaria, Yugoslavia, and Greece.

On the territory of Constantinople, there were six Russian churches before 1914. After the evacuation of the White Army, tens of thousands of Russian refugees lived there, organized into 20 communities. These refugees were joined by still more members of the White Army, who were quartered in Gallipoli and on Lemnos. The Church Abroad considered the church province of Constantinople to be its “first Russian Diocese.” [27] Nikon, Zhizneopisanie 5, p. 12. The SEA had its first session here in 1922. In addition to Metropolitans Anthony and Platon, Archbishops Anastasius and Theophanes and Bishop Benjamin were in the diocese at that time. The refugees lived in refugee camps, which had been erected in barracks outside the city. Within a short time, they had formed almost 80 different unions and organizations, which pursued political and cultural aims. A self-formed council took control of the coordination of these unions; Archbishop Anastasius presided over this council. [28] Ibid., pp. 11-15.

The mass of émigrés remained in Turkey only for a brief period of time and soon after the evacuation made arrangements to travel further because the economic outlook for establishing themselves there was extremely poor. Also, the SEA, and all the bishops except for Archbishop Anastasius, had left. The older émigrés and the sick remained behind, not having received entry visas from any country. Archbishop Anastasius remained in charge of this diocese until 1924. In the same year, he attended the Pan-Orthodox Congress, which was convened on the initiative of the Œcumenical Patriarch Meletius IV. At the Congress, the main themes were modernizations in the Church, such as the introduction of the New Calendar, second marriages for priests, and permitting married bishops. At this Congress, Archbishop Anastasius was the spokesman for the opposition, which was synonymous with opposing the Œcumenical Patriarch, who advocated many of the reforms. In subsequent weeks, there was a permanent deterioration of relations, which finally led to Archbishop Anastasius’ departure from Turkey in April of 1924. [29] Anastasius, Sbornik, pp. 12-13.

In subsequent years, relations between the Church Abroad and the Œcumenical Patriarchate deteriorated further still. The cause of this development was Constantinople’s granting of autonomy and autocephaly to the Orthodox Churches in Finland, the Baltics, and Poland. [30] Cf. Part V, Chap. 3.

No successor to Archbishop Anastasius was appointed. Most of the communities had, in the meantime, been dismantled, because the refugees had left the country. In the five years of its existence, 100,000 faithful had lived there. Permitting them their own bishop seems to have been more than justified. In the course of that year, practically all Russian émigrés left the country.

The few families remaining in Istanbul still have a church but have not had their own priests for many years.

In Greece, in the first years after the evacuation, there were a number of Russian refugee communities. After the Archbishop of Athens granted them an autonomous status, Archpriest P. Krakhmalev was given charge of the communities. In May of 1922, Bishop Hermogenes took over the communities. [31] Tserk. Ved. (1922) 10-11, p. 12; (1922) 14-15, p. 4. He remained head of the Russian diocese in Greece and the communities in Cyprus and Egypt until 1929, when he relinquished this position upon his appointment as Bishop of San Francisco and Western America, though he did not assume this position due to ill health and instead resided in Yugoslavia.

The focal point of the Russian communities in Greece was the Russian Church in Athens, which was built in 1850 and had served as the embassy church. In an Athens suburb, a Russian home for the elderly was built, which was supported by the Grand Duchess Helena Vladimirovna, who lived in Athens. In this home between sixty and eighty people lived. On the property, there was a small Russian chapel built in north Russian style and dedicated to St. Seraphim of Sarov. The Russian monks on Athos donated the icons and church utensils as a gift to the parish. Until the 1960s, Russian priests cared for the parishes in Athens and Piraeus. In the summers, several clergymen from North America and a few monks from Holy Trinity Monastery at Jordanville also spent a few months in the Russian old age home and served in the parishes in Athens and Piraeus. [32] Prav. Rus’ (1966) 18, p. 13; (1976) 22, p. 13.

Although the Diocese of Constantinople existed only until 1924, and the Diocese of Greece until 1929 [most of the émigrés had left by those years], the dioceses in Bulgaria and Yugoslavia existed until the end of World War II. In both countries, many thousands of émigrés lived until 1945, having formed their own communities and social organizations. Bulgaria, which had its own Black Sea ports, had received a part of the Russian refugees who had been evacuated overseas. In the first years after the defeat of the White Army, 50,000 Russian émigrés lived there. Whereas the Bulgarian people generally received the Russians with hospitality, the Bulgarian government was initially very reserved towards them. After Bulgaria’s War of Liberation against Turkey, friendly relations had existed between Russia and Bulgaria. During World War I, Bulgaria fought on the German side against Russia, which had supported the Serbian claim to Macedonia, but which Bulgaria claimed as a part of its country. The initially deplorable relationship improved quickly because King Boris III was amiably disposed towards the Russian émigrés. On the part of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church, the refugee clergy were well-received. Five Russian schools were opened with government support, which included kindergartens. Some two thousand Russian students completed their studies at Bulgarian universities, the majority with government stipends. Russian professors obtained positions in institutions of higher education there. Professors Glubokovsky, Poznov, Zyzykin, and Archpriest Shavelsky taught at the Theological Faculty of the University of Sofia. [33] Nikon, Zhizneopisanie, 5, p. 32. Despite these favorable conditions, half of the Russians left the country because labor conditions in an overwhelmingly agrarian state were poor. [34] Volkmann, p. 6. The others emigrated to France and Belgium where they found work in the industries and mines.

In Bulgaria, there were two Russian churches. In Sofia, there was a church at the former Russian embassy in honor of St. Nicholas, and in Shipka Pass there was a church in honor of St. Alexander Nevsky. They were built for those soldiers who were slain in the Russian-Turkish War.

Archimandrite Tikhon (Lyashchenko, later Bishop of Berlin and Germany) served at the embassy church in Sofia. In April of 1921, the SEA transferred the embassy churches in Sofia and Bucharest to Metropolitan Eulogius, while all other churches in the Balkans were subject to the SEA’s jurisdiction. [35] Manuchina, Evlogy, pp. 375-376. At the request of the Berlin community, Eulogius appointed Archimandrite Tikhon as a head clergyman in Berlin and transferred the community in Sofia to Bishop Seraphim (Sobolev). In August of the same year, the SEA charged Bishop Seraphim with the administration of all the Russian communities in Bulgaria. Metropolitan Eulogius accepted this arrangement. He himself wrote in his memoirs that “church affairs in Bulgaria had not interested him.” [36] Ibid., p. 438. This “disinterest” might, however, have more readily stemmed from the fact that the Russian communities in Bulgaria had left no doubt as to their canonical faithfulness to the Church Abroad, and their leader, Bishop Seraphim, was a theologically well-versed opponent to the teachings of Sergius Bulgakov. [37] JMP (1950) 4, pp. 21-28.

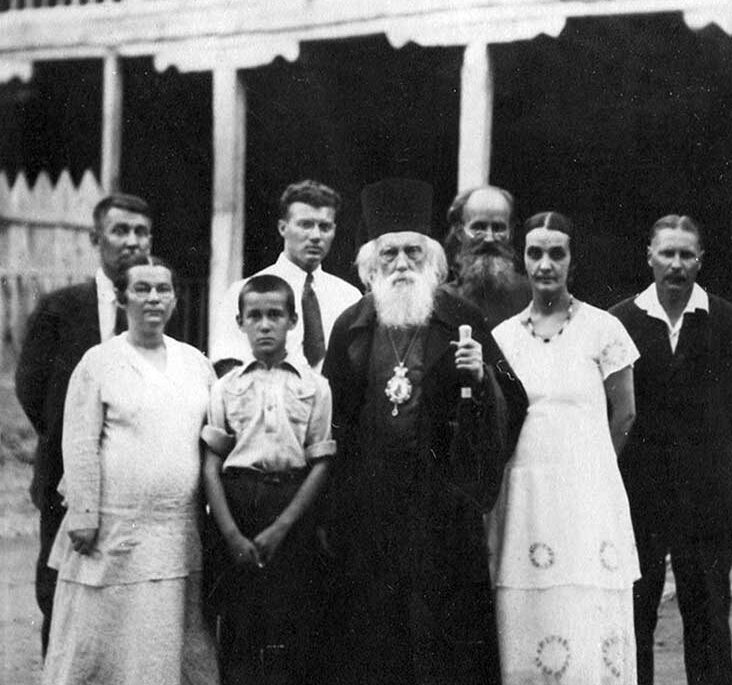

Bishop Seraphim was in charge of the Russian communities in Bulgaria from 1921 to 1950. He was elevated to archbishop for his services in 1934. Moreover, he had been the first bishop to be consecrated by the SEA before the evacuation. Besides him, Bishops Damian (Govorov) of Tsaritsyn and Bishop Theophanes (Bystrov) of Jamburg resided in Bulgaria.

Bishop Damian, (archbishop from 1931), lived from 1921 until his death in 1936 in Stanimaka (since 1934 Asenovgrad) in the Monastery of St. Cyril, where he established a pastoral school for the education of Russian clergy. [38] Cf. Part IV, Chap. 5. Bishop Theophanes lived from 1925 to 1931 at the Synodal residence in Sofia and led a reclusive life. He left his cell only to attend the divine services.

Seven Russian communities and two Russian monasteries were subject to Bishop Seraphim. The largest communities were in Sofia, Varna, Pernik, Plovdiv, and Stara Zagora. Besides the Russian churches in Sofia and at Shipka Pass there were no other Russian churches in the country. The Russian embassy church in Sofia was built in the years 1911-14, and after the end of World War II, it served as a parish church for the Russian émigrés in the country. When Bulgaria recognized the Soviet Union in 1934, this church became an object of contention because the Soviet government demanded that the “White Guard” leave the embassy church. To protect the interests of the émigrés, a committee was formed, presided over by Bishop Seraphim and the Bulgarian Bishop Boris; they finally succeeded in having the embassy church transferred to the Bulgarian Orthodox Church, which, in turn, rented the Bulgarian Church of St. Nicholas, which was located very near the former embassy church, to the émigrés. [39] Tserk. Zhizn´ (1934), p. 138. The remaining communities in Varna, Plovdiv, Pernik, and Stara Zagora used the Bulgarian Church’s houses of worship, including also former Greek churches. Such was the case in Varna, where the Russian community held their divine services in the Greek Church of St. Athanasius the Great. [40] Nikon, Zhizneopisanie, 7, p. 33.

At the Russian Memorial Church in Shipka Pass, there was a spacious building, which had originally served as a hostel. It was suggested that a pastoral school be opened in this building. However, when Bishop Damian was asked to open such a school in the Monastery of St. Cyril, the vacant house at Shipka Pass was turned into a home for invalids, which housed between 300 and 400 people. [41] Deyaniya Karlovtsakh, p. 75; Tserk. Zhizn´ (1934) p. 138.

Many Russian émigrés dispersed throughout the country, and where they could not form their own parishes, joined the Bulgarian Orthodox ones, as the divine services were celebrated in Church Slavonic. Refugee Russian priests were active in many communities, and they joined the Bulgarian Orthodox Church. A total of 100 priests and deacons of the Russian Church were assigned to care for Bulgarian parishes. [42] Pravoslavny Russky Kalendar’ (1927), p. 36.

In addition to these communities, there existed two smaller Russian monastic houses where refugee monks and nuns lived. The monastery was originally located in the Bulgarian Monastery of St. Alexander Nevsky at Jambol. Subsequently, in the 1920s, it moved to the Monastery of St. Cyril in Stanimaka in order to give support to Bishop Damian. [43] Seide, Klöster im Ausland; Ermakov. The Convent of the Protection of the Mother of God was located in Knyazhev. Both had some ten monastics.

In 1945, there was a reconciliation between the Bulgarian Church and the Russian Patriarchal Church. The Moscow Patriarchate also recognized Archbishop Seraphim as head of the Russian communities in Bulgaria after 1945 and did not, in practice, alter the status of the Russian communities, which, however, became subject to the Patriarchal Church. The Bulgarian Church and the Russian Patriarchal Church exchanged numerous visiting delegations. [44] JMP (1945) 5, pp. 19-24; (1945) 9, pp. 29-44; (1946) 6, pp. 3-19. In contrast to other countries where the Patriarchal Church attempted to move the émigré clergy, monks and nuns to return to the “homeland,” this seems not to have been the case in Bulgaria, because the émigré communities and the Russian monasteries continued to exist. After the death of Archbishop Seraphim in 1950, negotiations between the Patriarchal Church and the Bulgarian Church were concluded, with the agreement that all Russian parishes and monasteries in Bulgaria should be subject to the Bulgarian Orthodox Church. [45] Ibid. (1952) 7, pp. 32-46; (1953) 7, pp. 16-21. In this arrangement, the Russian Church in Sofia was excluded from this agreement and was designated a podvorye [metochion, dependency] of the Patriarchal Church. Since then, an archimandrite has been stationed there to serve as the head and representative of the Russian Church to the Bulgarian Church. [46] Ibid. (1978) 10, pp. 36-39; Russische Orthodoxe Kirche, “Einrichtungen,” p. 162. Thus ended the history of the Russian Church in Bulgaria, which had been a diocese of the Church Abroad until 1945 and thereafter a deanery of the Patriarchate for another seven years.

The Church Abroad had its center in Yugoslavia between the Wars. In contrast to numerous other countries, there was not a single Russian church in the country. The Serbian Patriarchate put many churches at the disposal of the émigrés. In Belgrade alone, two Russian churches were built with the support of the Serbian Patriarchate after 1920: Holy Trinity Church [47] Cf. the photographs of churches in Russ. Prav. Ts. 1, p. 41. On the history of both churches, see Nikon, Zhizneopisanie, 10, p. 223. in the center of Belgrade (near the Parliament) and the Chapel of the Iveron Icon of the Theotokos at the Russian cemetery in a suburb of Belgrade. Holy Trinity Church was built in a north Russian style, and its iconostasis was painted in the style of Andrew Rublev. Moreover, in this church, the wonderworking Kursk Icon of Theotokos, from the former Korennaya Hermitage, which since 1920 has been the principal holy object of the Church Abroad, was also venerated. The small church in honor of the Iveron Mother of God was a copy of the Moscow Church of the same name, which the Communists had destroyed. The iconostasis of this church was painted in the style of 19th century Russian Realism. Archimandrite Anthony (Bartosevich, later Archbishop of Western Europe) had frescoed the crypt and painted other icons in both churches as well. [48] JMP (1946) 5, pp. 37-44. Holy Trinity Church in Belgrade formed the church center for the several-thousand-strong Russian community. Here, many hierarchs of the Church Abroad were consecrate, and festive divine services were celebrated, in which often up to twelve bishops took part. At the cemetery near the Church of the Iveron Icon of the Theotokos émigré Russians, including Metropolitan Anthony, found their final resting place. [49] Nikon, Zhizneopisanie, 10, p. 223.

In Belgrade there were numerous educational institutions for Russian émigrés. Elementary and secondary schools, technical schools, and vocational courses of all types were instituted; libraries and cultural institutions were opened. The émigré professors received teaching positions at the universities and high schools of the country; students were able to continue their studies with government stipends. At the Belgrade Theological Faculty, sometimes as many as 200 Russian students were enrolled. Along with this there existed also political, economic and cultural unions and organizations. The Royal House and the Serbian Church financially supported the émigrés. [50] Ibid., 5, pp. 27-31, 73-138.

A total of 35,000-40,000 Russians lived in Yugoslavia. [51] Volkmann, p. 6. The majority of them, approximately 25,000, had come there after the evacuation of the Crimea, though large groups had begun to stream in as early as 1919 when the French began the first evacuations, and in the autumn of 1920, after the Bolshevik conquest of Novorossiisk. [52] Nikon, Zhizneopisanie, 5, p. 73. In February of 1920, the first group of Russian hierarchs arrived in Belgrade, including Archbishops Eulogius and George, and Bishops Metrophanes, Gabriel, and Apollinarius. [53] Bishop George of Minsk returned to Poland, where he died in 1923. Bishop Metrophanes of Sumi later joined the Serbian Patriarchate. They were met by the Russian Ambassador N. Strandtman. On the same day, Metropolitan [later Patriarch] Demetrius granted them an audience in the residence of the primate. [54] Nikon, Zhizneopisanie, 5, p. 27. The next day, Alexander, the Prince Regent (later King Alexander, 1921-1934) received them. Both Metropolitan Demetrius and the Prince Regent promised them every imaginable help and support, including a monthly stipend of 1,000 dinars. [55] Ibid., pp. 27, 74. All émigré bishops later received these allowances from the Yugoslav government, which established a “State Committee for the Support of the Russian Refugees in the Country.”

The Metropolitan (Patriarch from 1921) invited the Russian bishops to make Serbian monasteries their temporary residence. The majority of the bishops lived in later years in these monasteries, which were located in the Frushka Mountains, some ten miles south of Karlovtsy. There were 15 Serbian monasteries there, on account of which this area was often spoken of as the “Serbian Athos.” [56] Manuchina, Evlogy, p. 366.

The friendly reception which these first émigré hierarchs found in Serbia caused other Russian bishops to come to Serbia by the autumn of 1921, including Metropolitan Anthony, to whom the Serbian Patriarchate offered the old summer residence in Sremsky-Karlovtsy as a permanent headquarters for administration. In addition to Metropolitan Anthony, who had been living in Serbia since February of 1921, Archbishop Theophanes of Poltava, Bishops Benjamin of Sevastopol, Michael of Alexandrovsk, Theophanes of Kursk, Sergius of Chernomorsk and Hermogenes of Ekaterinoslav emigrated to Yugoslavia. [57] Nikon, Zhizneopisanie, 5, p. 28. In Karlovtsy, where Metropolitan Anthony resided, the First and Second Pan-Diaspora Councils met, as well as a dozen councils of Bishops of the Church Abroad. Here in the years 1934-35, the negotiations for the reconciliation of the schism of the church emigration took place. Numerous bishops of the Church Abroad traveled to the sessions of the Council of Bishops in Karlovtsy, including Metropolitans Platon and Theophilus from North America, Meletius from the Far East, Archbishops Anastasius, Seraphim, Tikhon, Nestor, and others.

The Russian hierarchs also promised to rejuvenate Serbian Orthodox church life. Thus, the nuns of the former Lesna Convent, who had first found refuge in Romanian Bessarabia, were invited to Serbia, where they found a new home in the former Serbian monastery in Hopovo in the Frushka Mountains. The invitation was accompanied by the hope that the convent would be able to reawaken Serbian woman’s monasticism. This wish was more than fulfilled in the 25 years the convent remained in Serbia; a total of 27 convents and communities of nuns were founded by the Lesna nuns. In many of the new Serbian convents, Russian nuns assumed the leadership and educated the Serbian sisters, who were enabled to lead and establish new convents. The Russian convent of the Lesna sisters took over the supervision of the Serbian convents. Not only Serbian woman’s monasticism reawakened through the efforts of the Church Abroad, but also Serbian men’s monasticism experienced new life through the influx of Russian monks. The Milkovo Monastery at Lapovo, in which some 25 Russian monks lived, was a spiritual and ecclesiastical center for both the Church Abroad and for the Serbian Church. [58] Seide, Klöster im Ausland. The great importance of the Russian Church emigration for the Serbian Church is clearly documented in the fact that the Serbian Patriarch transferred the supervision of Serbian monasteries and convents to Metropolitan Anthony, whereby the entire monastic life of the Serbian Church came under the spiritual supervision of the Church Abroad.

The leadership of the Russian communities in Yugoslavia was in the hands of Metropolitan Anthony from 1921 until 1936, then from 1936 until 1943/44 in the hands of Metropolitan Anastasius. After the outbreak of the War, the beginning of the Communist partisan struggle and the creation of the Croatian Ustashi state, the bloodiest epoch in the history of the Serbian Church, began. The Russian émigré communities were also caught up in this persecution. In the first months of 1943 alone, five Russian priests were murdered by Communist partisans. [59] Tserk. Zhizn´ (1943) 5, p. 75. The Lesna Convent was attacked and pillaged many times and finally burnt down in 1943. Monks, nuns, clergy, and faithful fled the war zone and retreated to the larger cities, whence finally many fled from the advancing Soviet troops to Germany in 1943/44.

In the spring of 1945, representatives of the Moscow Patriarchate entered Belgrade in order to negotiate the annexation of the Russian communities in the country. The representatives of the State, which in the meantime had come to be ruled by Communists, received these emissaries in a friendly manner. The Serbian Church, which had supported the émigré Church − alienated from the [Moscow] Patriarchate − conducted itself in a reserved manner and did not participate in numerous receptions. The Journal of the Moscow Patriarchate generally reported that the Russian émigrés there had expressed the wish to be reunited with the Mother Church and to return to the Soviet Union, though this did not actually reflect the facts, as was shown later after the break between Tito and Stalin, [60]JMP (1945) 6, pp. 18-28; (1946) 5, pp. 27-44. This is a detailed report on the meetings with representatives of the government. There is no mention of a meeting with representatives of the Serbian … Continue reading when the Yugoslav government permitted the Russian émigrés to emigrate to the West. Many refugees who had not left the country in time in 1944 now arrived in the West, including the sisters of the Lesna Convent, Archimandrite Anthony (Bartosevich), and many clergymen. After 1944, Archpriest Neklyudov first took over the leadership of the Russian communities; he was the rector of Holy Trinity Church in Belgrade, then Archpriest Sokal, and from 1950, Archpriest Tarasiev. [61] Cf. Part II, Chap. 1, p. 85; JMP (1956) 5, pp. 67-75. In 1954, contacts were resumed between the Russian Patriarchal Church and the Serbian Church, the Russian Church subordinated all the communities and churches to the Serbian Church and retained only the Russian Holy Trinity Church in Belgrade under its jurisdiction, which has since then served as the Russian Church’s representation to the Serbian Church. [62] Russisch Orthodoxe Kirche, “Einrichtungen,” pp. 161-162.

Approximately 30,000 Russians emigrated to Czechoslovakia. [63] Volkmann, p. 6. Above all else, these were the members of the Russian intelligentsia, who were politically on the liberal, left-wing of the emigration and were primarily anticlerical. Among the refugees there were 5,000 students and nearly 1,500 professors, teachers, academicians, and artists. [64] Nikon, Zhizneopisanie, 5, pp. 34-35. Most of the students were able to continue their studies at Czech universities with government stipends; professors and teachers received positions in schools and high schools there. After the émigrés established their own academic institutes, including the Russian Faculty, the Handel Academy, the People’s University and other institutions, many of them taught at these. [65] Ibid., p. 34.

In many spa resorts in Czechoslovakia, there were Russian churches that had been founded in the 19th century, when Russian families traveled to these baths to “take the cure”. There were churches in Marienbad, Franzenbad, Karlsbad, Pilsen, and Pressburg. In Prague, there was the Russian Church of St. Nicholas and, at the Russian (Olshinsky) Cemetery, the Chapel of the Dormition, which was under Bishop Sergius (Korolev), who joined Metropolitan Eulogius.

All Russian parishes belonged to Metropolitan Eulogius’ West European Diocese. According to the decisions of the Council of Bishops of 1923, Metropolitan Eulogius was supposed to create vicariates, including a vicariate for the Russian community in Czechoslovakia. After the Polish authorities expelled Bishop Sergius (Korolev), Metropolitan Eulogius appointed Bishop Sergius vicar bishop of Czechoslovakia with his see in Prague. The vicariate belonged to the Church Abroad for two more years; then Bishop Sergius joined the Paris Jurisdiction after the schism of 1926. Of the communities, only a part of the Prague parishes and the communities in Brunn and Pressburg joined in this break. [66] Manuchina, Evlogy, pp. 459-461; Nikon, Zhizneopisanie, 7, p. 234.

Until the National Socialist new order for Central Europe, this situation remained unchanged. After the establishment of the Central European Metropolitanate, whose head was Metropolitan Seraphim (Lade), the communities of the “Protectorate” [Czechoslovakia] were united with the Church Abroad upon the demands of the National Socialist rulers. Bishop Gorazd was martyred. Bishop Sergius joined the Synod. Yet this church restructuring was not of long duration. With the Soviet invasion, the Church Abroad also lost its parishes in Czechoslovakia.

They were then made subject to the Moscow Patriarchate, which maintained an exarchate in Czechoslovakia until 1951, when the Orthodox Autocephalous Church of Czechoslovakia took over all the parishes. [67] JMP (1945) 11, pp. 14-21. Bishop Sergius (Korolev), who remained in Prague, as well as the Bishops of the Ukrainian Autonomous Orthodox Church, who were overtaken in their flight to the West by the Soviet troops, were forced to recognize the Moscow Patriarchate and to “return to the homeland.” These were Bishops Daniel (Yuzviuk), Anthony (Marchenko), and John (Lavrinenko). [68] In the spirit of “new Soviet Patriotism,” they reported on their “return to the homeland,” which they had left only a few weeks earlier, cf. JMP (1946) 9, pp. 54-64.

The spiritual and ecclesiastical center of the Russian emigration in Czechoslovakia from the mid-1920s was, however, the Monastery of St. Job in Ladomirova in eastern Slovakia (Kreis Svidnik). [69] Seide, “Klöster im Ausland/Monasteries”. The Orthodox in the Carpathians had been part of the Serbian Orthodox Church since 1919, because of a pact between Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia, which gave Serbia rightful jurisdiction over the Diocese of Preshov-Mukachevo. Bishop Vladimir (Liubomir Raich) was the ruling bishop. After many Uniates in this area left the Unia and returned to Orthodoxy, a plan was developed to establish an Orthodox Mission there, which would minister to the faithful with literature and care for their souls. Ladomirova was chosen as the location for this; the inhabitants there had been the first to have left the Unia and return to Orthodoxy. [70] Vitalis, p. 193; Heger, p. 20ff.; JMP (1957) 5, pp. 61-65.

Archimandrite Vitalis (Maximenko), who planned to build a monastery with a printing press, took over the direction of the Mission. [71] Cf. Part IV, Chap. 3. In the course of a few years, he had founded the Monastery of St. Job of Pochaev and the printing press of the same name, which became the most significant printing press of the Church Abroad before World War II. Many renowned hierarchs have originated from the brotherhood of the monastery, such as Archbishop Vitalis (Maximenko), Archbishop Seraphim (Ivanov), Metropolitan Vitalis (Ustinov), Bishop Nathaniel (Lvov), Archbishop Laurus (Skurla), and others. The Brotherhood fled to Germany and overseas before the advancing Soviet troops in 1944. Many of the Church Abroad’s present-day monasteries and printing presses would be hard to imagine without the St. Job Brotherhood.

Except for the Church of the Archangel Michael, the monastery in Ladomirova was destroyed. [72] Tserkovnaya letopis’ [Lausanne] (1946) pp. 28-29. In Hungary, according to the census of 1930, 1,687 Russian émigrés lived. [73] Seide, Ungarische Kirche, p. 108. They cared for a small church in Budapest. After the schism of 1926, this community divided. From that time, there were two Russian parishes in Budapest, which belonged to the two different jurisdictions. [74] Tserk. Zhizn’ (1942) 7, pp. 108-110. After the outbreak of the World War II, both parishes, as well as the Hungarian-speaking Orthodox communities, were united with the Church Abroad and placed under the direction of a Russian priest. After the Soviet occupation of Hungary, the Moscow Patriarchate established a Russian deanery for the Orthodox communities under its jurisdiction. The Russian parish had hardly any faithful after 1945 because most émigrés had fled to the West. [75] Seide, Ungarische Kirche, pp. 110-113; Russisch Orthodoxe Kirche, “Einrichtungen,” pp. 159-160; JMP (1954) 4, pp. 13-15.

References

| ↵1 | Dubanaitis, pp.153-154; Laatsi, pp. 63-73; Kahle, pp. 89-107. Jahrbuch der Orthodoxie 1976/77, pp. 37-38, 158-160, 163-164. |

|---|---|

| ↵2 | Prav Rus´ (1938) 1, p. 2. |

| ↵3 | On the situation of Orthodoxy in Poland between the wars, see Lissek, Orthodoxe Kirche in Polen; Verdernikov, Delo polskoi tserkvi; Zheleznyakovich, K istorii… v Polshe; Popov, Gonenie… v Polshe. After the re-annexation of this territory by the Soviet Union, there was a movement to revive Orthodoxy, which was particularly directed against the Uniates, whose Church was forbidden. |

| ↵4 | Cf. Part V; Dubnaitis, p. 153. |

| ↵5 | K. Soop, & U. Keskkjula, Kuremyaevsky monastyr’; Zybkovets, p. 127. |

| ↵6 | JMP (1945) 4, pp. 3-6. |

| ↵7 | Dubnaitis, p. 154. |

| ↵8 | Zybkovets, p. 127. |

| ↵9 | Cf. Part I, Chap. 3, note 30. |

| ↵10 | Balevic, p. 13 − This work by Balevic explains the development of the Latvian Church. Despite its Marxist Soviet standpoint, it includes important facts on the history of Orthodoxy in Latvia. Cf. also Part I, Chap. 3, note 11. |

| ↵11 | Balevic, pp. 14-15. |

| ↵12 | Prav. Rus’ (1955) 21, p. 12; “The Orthodox Church Under German Occupation” in Eastern Churches Review (1974) pp. 131-161. |

| ↵13 | Metropolitan Vladimir, pp. 156-157: on the biography of Metropolitan Panteleimon. |

| ↵14 | Jahrbuch der Orthodoxie 1976/77, pp. 158-162. |

| ↵15 | On the history of the Ukrainian and Belorussian Autonomous Orthodox Churches, cf. Part I, Chap. 6, p. 75f. |

| ↵16 | Glubokovsky, Voina i mir; Zheleznyakovich, Finlandskaya tserkov’; Tserkovnye Vedomosti (1924) 19-20, p. 6. |

| ↵17 | Prav. Rus’ (1937) 11, p. 5. From 1945 there were parishes in Vyborg and Helsingfors, which belonged to the Patriarchal Church: JMP (1945) 11, pp. 5-13; (1953) 9, pp. 7-18; (1959) 1, pp. 60-63; Russische Orthodoxe Kirche “Einrichtungen,” p. 161. |

| ↵18 | Cf. Part I, Chap. 4. |

| ↵19 | In Czechoslovakia after 1922 there was a small Czech Orthodox Church under the leadership of a former Catholic, Bishop Gorazd (Pavlik), to which 1,000 faithful belonged. This Church was under the jurisdiction of the Serbian Church. |

| ↵20 | Grabbe, Tserkov’ i uchenie 1, pp. 267-268. |

| ↵21 | Nikon, Zhizneopisanie 7, p. 234. |

| ↵22 | After the Soviet annexation of this territory, the Serbian Church relinquished its diocese, which in turn became part of the Russian Church. Russie et Chretiente (1947) pp. 89-90; JMP (1945) 11, pp. 14-19; (1950) 4, pp. 10-18. |

| ↵23 | D´Herbigny/Deubner, Evêques Russes, p. 16. |

| ↵24 | Nikon, Zhizneopisanie 5, pp. 6-11. |

| ↵25 | D´Herbigny/Deubner, Eveques Russes, p. 18; Tserk. Ved. (1922) 2, p. 9; Ibid. 3, pp. 7-8. |

| ↵26 | Ibid., 11-12, p. 12. |

| ↵27 | Nikon, Zhizneopisanie 5, p. 12. |

| ↵28 | Ibid., pp. 11-15. |

| ↵29 | Anastasius, Sbornik, pp. 12-13. |

| ↵30 | Cf. Part V, Chap. 3. |

| ↵31 | Tserk. Ved. (1922) 10-11, p. 12; (1922) 14-15, p. 4. |

| ↵32 | Prav. Rus’ (1966) 18, p. 13; (1976) 22, p. 13. |

| ↵33 | Nikon, Zhizneopisanie, 5, p. 32. |

| ↵34 | Volkmann, p. 6. |

| ↵35 | Manuchina, Evlogy, pp. 375-376. |

| ↵36 | Ibid., p. 438. |

| ↵37 | JMP (1950) 4, pp. 21-28. |

| ↵38 | Cf. Part IV, Chap. 5. |

| ↵39 | Tserk. Zhizn´ (1934), p. 138. |

| ↵40 | Nikon, Zhizneopisanie, 7, p. 33. |

| ↵41 | Deyaniya Karlovtsakh, p. 75; Tserk. Zhizn´ (1934) p. 138. |

| ↵42 | Pravoslavny Russky Kalendar’ (1927), p. 36. |

| ↵43 | Seide, Klöster im Ausland; Ermakov. |

| ↵44 | JMP (1945) 5, pp. 19-24; (1945) 9, pp. 29-44; (1946) 6, pp. 3-19. |

| ↵45 | Ibid. (1952) 7, pp. 32-46; (1953) 7, pp. 16-21. |

| ↵46 | Ibid. (1978) 10, pp. 36-39; Russische Orthodoxe Kirche, “Einrichtungen,” p. 162. |

| ↵47 | Cf. the photographs of churches in Russ. Prav. Ts. 1, p. 41. On the history of both churches, see Nikon, Zhizneopisanie, 10, p. 223. |

| ↵48 | JMP (1946) 5, pp. 37-44. |

| ↵49 | Nikon, Zhizneopisanie, 10, p. 223. |

| ↵50 | Ibid., 5, pp. 27-31, 73-138. |

| ↵51 | Volkmann, p. 6. |

| ↵52 | Nikon, Zhizneopisanie, 5, p. 73. |

| ↵53 | Bishop George of Minsk returned to Poland, where he died in 1923. Bishop Metrophanes of Sumi later joined the Serbian Patriarchate. |

| ↵54 | Nikon, Zhizneopisanie, 5, p. 27. |

| ↵55 | Ibid., pp. 27, 74. All émigré bishops later received these allowances from the Yugoslav government, which established a “State Committee for the Support of the Russian Refugees in the Country.” |

| ↵56 | Manuchina, Evlogy, p. 366. |

| ↵57 | Nikon, Zhizneopisanie, 5, p. 28. |

| ↵58 | Seide, Klöster im Ausland. |

| ↵59 | Tserk. Zhizn´ (1943) 5, p. 75. |

| ↵60 | JMP (1945) 6, pp. 18-28; (1946) 5, pp. 27-44. This is a detailed report on the meetings with representatives of the government. There is no mention of a meeting with representatives of the Serbian Church. Cf. JMP (1948) 1, pp. 66-69; (1948) 7, p. 64. |

| ↵61 | Cf. Part II, Chap. 1, p. 85; JMP (1956) 5, pp. 67-75. |

| ↵62 | Russisch Orthodoxe Kirche, “Einrichtungen,” pp. 161-162. |

| ↵63 | Volkmann, p. 6. |

| ↵64 | Nikon, Zhizneopisanie, 5, pp. 34-35. |

| ↵65 | Ibid., p. 34. |

| ↵66 | Manuchina, Evlogy, pp. 459-461; Nikon, Zhizneopisanie, 7, p. 234. |

| ↵67 | JMP (1945) 11, pp. 14-21. |

| ↵68 | In the spirit of “new Soviet Patriotism,” they reported on their “return to the homeland,” which they had left only a few weeks earlier, cf. JMP (1946) 9, pp. 54-64. |

| ↵69 | Seide, “Klöster im Ausland/Monasteries”. |

| ↵70 | Vitalis, p. 193; Heger, p. 20ff.; JMP (1957) 5, pp. 61-65. |

| ↵71 | Cf. Part IV, Chap. 3. |

| ↵72 | Tserkovnaya letopis’ [Lausanne] (1946) pp. 28-29. |

| ↵73 | Seide, Ungarische Kirche, p. 108. |

| ↵74 | Tserk. Zhizn’ (1942) 7, pp. 108-110. |

| ↵75 | Seide, Ungarische Kirche, pp. 110-113; Russisch Orthodoxe Kirche, “Einrichtungen,” pp. 159-160; JMP (1954) 4, pp. 13-15. |