Part IV, Chapter 2

Monasteries & Convents of the Church Abroad

& Their Significance for the Church Life of the Emigration

Most closely linked with the spiritual and ecclesiastical life of the Russian Orthodox Church are its monasteries and convents. This held true for the Russian Church before 1917, and it does for the Russian Church Abroad as well. Before the October Revolution, there was no country in which the monastic life was held in such high regard as in the Russian Empire. Since the end of the 19th century, monastic life there had been experiencing a revival. In the 30 years before the Revolution, 300 monasteries were established. In the more than 1200 monasteries that existed in 1917, there lived 33,572 monks and nuns and 73,462 novices. A large number of novices, primarily younger people, most conspicuously documents the attraction that the monasteries exercised on young people. It was not so much the large monastic centers, the lavra-monasteries that attracted the young people, but rather the remote “wilderness-monasteries.” [1]There is a 180-page manuscript about the monasteries of the Church Abroad. Regarding the publication of the manuscript, see above, p. XI. [Trans., Monasteries and Convents of the Church Abroad was … Continue reading

The Bolshevik seizure of power endangered the very existence of the monasteries, and their properties were supposed to be nationalized by 1921. This goal was not reached in so brief a period of time, although the monasteries’ continued existence was greatly challenged. Within three years, 722 out of 1,257 monasteries were closed. If one eliminates another the 100 or so monasteries that ended up outside the Soviet Union after the new national boundaries were established in Eastern Europe, then in Russia itself there were only about 300 monasteries, mostly smaller communities. All these monasteries and convents were also closed by 1929/30.

The mass closure of monasteries and the expulsion of their inhabitants could only outwardly terminate the existence of monastic communities, but not the idea of monasticism.

After the expulsion, monks and nuns held fast to their monastic vows and founded communities at homes in remote areas of the country. The maintenance of the monastic ideal and its deep roots within the people became clear when, in 1941-44, new monasteries came into existence everywhere in the country.

The German occupation of the Western parts of the Soviet Union during World War II led to a religious renaissance, which not only overcame but also showed the uselessness of the atheist propaganda. Within a few years, many closed churches were reopened, including venerable monasteries such as the Kiev-Caves Lavra, Holy Trinity-St. Sergius Lavra, St. Florus and Holy Protection Convent in Kiev, and many more. Within a few weeks of the reopenings, 100-300 monks or nuns had come to live in them, having returned from exile or emerged from underground. By the end of World War II, 104 monasteries and convents had opened, of which 69 were still in existence in 1958 and at present only 16. [2] Seide, Klöster des Patriarchats, pp. 8-17; Tserk. Zhizn’ (1942), pp. 108, 156. In these 16 monasteries, there lived over 1,000 monks and nuns at the beginning of the 1970s; whereas in 1946 there had been 5,000. [3] From the secret Furov Report, Part 3: “The Monasteries of the Russian Orthodox Church”, German version in “Glaube in der 2-en Welt” (1980), pp. 43-48.

The decline of the monasteries and monasticism can only be explained by the government’s coercive measures against monastic communities. The ultimate goal of this policy is the complete closure of all monasteries, because the atheistic concept is that the “institution of monasticism has entered its final arena <…> and in the socialist society <…> it is nothing more than an anachronism.” [4] Zybkovets, p. 112. Yet already in the 1920s and 1930s, these same authors also had to admit that in the “remote corners” of Siberia, the so-called wilderness monasteries and cells were reestablished, founded by groups that would not recognize Soviet laws and refused to serve in the army.” [5] Ibid., p. 111. The state’s coercive measures in the last twenty years have led to a situation where more Russian monasteries are located outside the Soviet Union than within. The Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia has more than twenty monastic houses; the autocephalous Orthodox Church in America has five; [6] Yearbook of Orthodoxy (1976/1977), pp. 203-204; C. Tarasar, J. Erickson, pp. 102-112 & 302. and the Russian Orthodox Archdiocese of Western Europe has one convent in France. [7] ”In a Russian Convent” in Glaube in der 2-en Welt (1980) 5, pp. 1-2; ECR (1978) 1-2, p. 153. In addition to these, there is another convent in Israel, the Ein Karim convent, and a monastery and convent in the Hague (both a part of the Dutch Orthodox Church); these three are subject to the Patriarchal Church. Therefore, there are more than 30 monastic communities abroad that can be traced back to the Orthodox Church in Russia.

The idea of monasticism was always most firmly rooted in the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad. The Paris Jurisdiction had indeed made various attempts to establish monasteries, yet they were never entirely sucessful. Before the War, there were three small sketes in France, which existed for a few years. Metropolitan Eulogius himself wrote with resignation in his memoirs that “monasticism could not blossom in the emigration.” [8] Manuchina, pp. 563-573. This may have been the case for the Paris Jurisdiction, though it has in no way held true for the Church Abroad which, during Metropolitan Eulogius’s lifetime, had significant monasteries and convents. For the first time, Mother Eudoxia’s initiative to establish a convent near Bussy-en-Othe (Dep. Yonne) succeeded in 1946; at this time, ten nuns belong to it, including five Russians.

The OCA has five monastic communities today, including St. Tikhon’s Monastery. It is the oldest monastery on American soil and was founded by Patriarch Tikhon, then Bishop, in 1905. During the period between the Wars, 20 to 30 monks belonged to the monastery. Since then, the number has declined. At the present time, between five and ten monks live there.

North of San Francisco, near Calistoga, there is a convent in which six nuns live; they had belonged to the Church Abroad’s former convent in Harbin and, after their flight in 1946, they joined the North American Metropolia. In addition to these two, there are another two convents and one monastery in New York State and Pennsylvania, which are primarily inhabited by Americans who converted to Orthodoxy. English is the language used in these monastic houses. [9] Jahrbuch der Orthodoxie (1976/1977), pp. 171-173.

It is thus understandable that the Church Abroad considers itself the guardian of the tradition of Russian monasteries and has attempted to stand guard over the goals and tasks of the Russian monasteries from pre-Revolutionary times.

The monastic communities see as their most important tasks the care of the faithful who seek out the monastery to venerate its shrines and to pray together with the monks and nuns, as well as to pray and meditate.

Before World War II, the Church Abroad considered the monasteries to be a departure point for a reanimation of Russian monasticism, after the monastic communities in the homeland had been dissolved and the monasteries and convents themselves shut. At the Council that took place in 1938 in Karlovtsy, Archimandrite Seraphim (Ivanov, from 1947 bishop) presented an extensive report on “The Monasteries and Monasticism.” [10] Seraphim, pp. 377-388. In his presentation, he pointed to the historical and cultural significance of Russian monasticism in the history of Russia. In addition to this, monasticism has earned great renown as the guardian and caretaker of the old shrines of the most important churches and monasteries. In order to continue these aims, it would be necessary to establish monastic schools in the larger monasteries of the Church Abroad. In these preparatory schools, candidates for monasticism should be acquainted with the rules of the monastery and be trained in ecclesiastical chant, in psalm reading, and so forth. These schools were supposed to be an introductory course before reception. After their reception into the monastery, the future monks were to be educated in missionary courses for service in the church and the monasteries. They should also be acquainted with the ecclesiastical canons, the organization of parishes and monasteries, in order to form a cadre for the rebuilding of church life in Russia, when it is liberated. The most important task would, however, consist of preparing their own candidates, who could reestablish the old monasticism in a liberated Russia, which would be in a position to rebuild the large printing presses in the Kiev-Caves Lavra, in the Pochaev Lavra, in Holy Trinity-St. Sergius Monastery, in Shamordino Convent and in others.

These cadres should be taught and provided with experience to administer the monasteries and to be able to fulfill the social and charitable functions thereof. To this end, the monasteries of the emigration should be divided into the following main categories: (1) missionary monasteries with missionary courses and monastic schools, (2) monasteries with monastic printing presses and their own publishing houses, (3) monasteries with social and charitable functions for the care of orphans and the elderly, hospitals, asylums, etc., and (4) monasteries for the contemplative life. All monasteries should, as far as possible, be self-administered. The abbot was usually an archimandrite or a bishop.

During the time between the Wars as well, as in the present, the Church Abroad’s monasteries have fit into these categories. In the St. Job Monastery in Ladomirova, and in the Convent of the Kazan’ Icon of the Mother of God in Harbin, there were sizeable printing presses. Since the 1930s, monastics were educated in them, and their own courses for missionaries and monks were instituted. They were supported by the Milkovo Monastery and the Convent of the Lesna Icon of the Mother of God in Yugoslavia, in which monks and nuns were educated who could take over the administration of a convent. St. Tikhon’s Monastery in the U.S.A., the Convent of the Vladimir Icon of the Mother of God with its sister convent, the Lesna Convent and the Bethany Convent, all maintained orphanages. The Kazan’ Convent in Harbin maintained a home for the elderly and a nursing home, as well as a clinic with several doctors, and had its own pharmacy. If the Church Abroad could show evidence that it was in a position to continue the tradition of the old Russian monasteries, then its claim that its monasteries were supposed to form a departure point for reanimation of the Russian monasteries in the homeland was not totally unrealistic. Between the Wars, the Lesna Convent in Yugoslavia was the focal point of the renewal of Serbian woman’s monasticism. Due to the Lesna Convent’s missionary activities, 32 larger convents and numerous smaller sisterhoods were established. [11] Prav. Rus’ (1960) 18, p. 5. Yet it was not only the Serbian convents that experienced a fresh impetus due to the refugee Russian nuns; the monasteries also experienced a renaissance, for which by in large they have the Russian Church Abroad to thank. The Russian Milkovo Monastery was for Russian and Serbian monks — a spiritual center for the Church Abroad and for the Serbian Church in like measure. The great significance of the Russian emigration for the Serbian Orthodox Church is clearly testified to by the fact that the Serbian Patriarch transferred the supervision of the Serbian monasteries to the Russian Metropolitan Anthony (Khrapovitsky) and subjected all Serbian convents to the Russian Lesna Convent in Hopovo. [12]N. Schidlovskaya; Z. Frid, pp. 8-12. In 1978 there were 160 Orthodox monasteries in Serbia with 1,100 monks and nuns. The largest monastery is Studnica Monastery with 15 monks; the largest convent is … Continue reading

Among the refugees that had left Russia after the Revolution and Civil War were also numerous monks and nuns. Outside the borders of Russia, monasteries already existed: a monastery in Peking (the Dormition Monastery) with a podvorye in Peking and Harbin, as well as a convent in Harbin (the Dormition Convent). Both belonged to the Peking Ecclesiastical Mission. In the monastery, five monks lived, in both of the podvoryes three monks, and in the convent ten nuns. In the U.S.A., there was St. Tikhon’s Monastery, which had no monks in 1917, a skete in Alaska (St. Triphon’s Monastery) with two monks, and the Holy Virgin Protection Convent in Springfield [New Hampshire] with five nuns. Except for St. Tikhon’s, no other monks and nuns lived in these monasteries and convents in the 1930s. The Ein Karem Convent with 20 nuns was in existence in the Holy Land. [13] Zybkovets, pp. 196-197. The building of the Convent of the Ascension on the Mount of Olives was suspended on account of the War. On Mt. Athos, in the Russian monasteries and cells, there lived some 1,000 Russian monks, and in the monasteries on the islands of Valaam and Konevets another 300 monks. These monasteries were subject to the Ecumenical Patriarch from 1920, like the Mt. Athos monasteries. Some 100 Russian monasteries existed in Bessarabia, Poland and the Baltics between the Wars, and were subject to the local Orthodox Churches of these countries.

Whereas a smaller number of monks and nuns were able to gain entry into the already-existing monasteries and convents, the great majority had to find new housing venues. In Yugoslavia and Bulgaria, the national Churches gave them empty convents. In Czechoslovakia, Manchuria, China, and the Holy Land, new monasteries were built, and old buildings were reoccupied. In North America, the schism of the North American communities led to the establishment of Holy Trinity Monastery in Jordanville, which today forms the spiritual and ecclesiastical center of the Church Abroad.

Before the outbreak of World War II, 180 monks and 40 novices and 450 nuns lived in the monasteries of the Church Abroad. Monasteries were located in the following places: in Palestine – 2 monasteries and the Jerusalem Ecclesiastical Mission with 20 monks, 4 convents with 200 nuns; in Serbia –1 monastery with 25 monks and 1 convent with 70 nuns; in Bulgaria – 1 monastery and 1 convent with 10 inhabitants; in Czechoslovakia – 1 monastery with 30 monks; in China – 1 monastery with 2 podvoryes and 26 monks and 1 convent with 3 podvoryes and 40 nuns; in Manchuria 1 monastery and 1 convent with 30 monks and 40 novices and 30 nuns; and finally in the U.S.A. – 2 monasteries with 40 monks. [14] Seraphim, pp. 386-387.

Most monks and nuns who lived in the monasteries and convents in the 1920s had received their tonsure – or had professed – before the Revolution; however, during the 1930s, a change of generations took place. More and more candidates came from the ranks of the émigrés. In Ein Karem, and the Vladimir Mother of God Convent in Yugoslavia, there were large groups of nuns, who had already formed a community before the Revolution. Yet also in these convents, there were new candidates. If the Lesna Convent, for example, had 35-40 nuns at all times, then one must not forget that the newly-founded convent was always dispatching nuns, and in this way in the course of the years, more than 30 nuns were released from its community. The Ein Karem Convent in the Holy Land has constantly had approximately 40 nuns. At the end of the 1930s, 300 nuns lived in the Holy Land. In St. Job Monastery in Czechoslovakia, in St. Tikhon’s, and in Holy Trinity Monastery in the U.S.A., there were monks who came exclusively from the ranks of the émigrés. To the 180 monks and 40 novices who lived in the monasteries, one must, of course, add the higher clergy (there were 28 bishops) and the many hieromonks of all ranks, who served as parish and monastery clergy. Their number is not precisely known, though it may have exceeded 100. Thus, before World War II, the Church Abroad had some 300-350 monastic members and 450 nuns.

These numbers underscore the fact that, before World War II, the Church Abroad could not have been wrong in claiming to be the Russian Exile Church. It is understandable that after the reunification with the American Metropolia, the Paris Jurisdiction could only be viewed as schismatic.

As a consequence of World War II, the Church Abroad lost nearly all its monasteries.

Excluding the monasteries in the Holy Land, after 1945 the Church Abroad had only Holy Trinity Monastery in Jordanville, in which approximately 10 monks lived. If its jurisdiction today again has 20 monasteries and sketes, this is proof of how firmly the monastic ideal is rooted in the faithful and what great respect the monasteries enjoy.

This is borne witness above all by the following facts: year after year, thousands of faithful make pilgrimages to the monasteries’ feasts, thereby documenting their closeness to their Church and its monasteries. The reestablishment of the monastic communities after 1945 was facilitated by their donations and support. Today, monasteries and convents exist wherever the Church Abroad is present: in Western Europe, North and South America, in Australia and in the Holy Land. [15] Spisok (1980/1981).

Among the 20 monasteries and sketes was a Greek monastery and a Greek convent, and an English-speaking convent in the U.S.A. Except for these three, Russian has remained the spoken language in all other monasteries, and Church Slavonic is used in the celebration of the divine services. The most unexpected thing, however, is that all monasteries, after having experienced a slight decline in the 1960s, have admitted more candidates over the past several years. Thus today, of the 40 monks in Holy Trinity Monastery in Jordanville about half are under forty years of age, including seven novices between 20 and 25. Holy Transfiguration Monastery in Boston has 30 monks, mostly younger ones. The latter monastery follows the Athonite monastic rule with strict asceticism and lengthy services and prayers. The preservation of the old traditions of the Russian convents and the strict adherence to the monastic rules are also the reason that the monastery of the Church Abroad today again has more candidates than, for example, the monasteries of the O.C.A. If the Church Abroad is often accused of “stagnant conservatism,” these critics suppress the fact that the Church Abroad alone holds fast to the sacred traditions of Orthodoxy and strives to preserve the inheritance of the pre-Revolutionary Russian Church. The unwillingness to compromise with the false reforms like the abridgment of the Liturgy, as is practiced in many Orthodox Churches, a deviation from the monastery rules is unthinkable for the Church Abroad. Their clear stance has, however, also attracted many new members in the last twenty years, including new candidates for its monasteries.

Among the candidates who enter the monasteries today, there are the late vocations, who take up the monastic life after being widowed or reaching retirement age, as well as young people who come from traditional Orthodox families, but have for a time lost contact with the Church. This is, for example, also the case in the U.S.A., where the descendants of Uniate and Orthodox immigrant families have again found Orthodoxy. Many candidates are from the ranks of the converts or the recent immigrants from the Soviet Union. At the current time, there are three new candidates in the Lesna Mother of God Convent, all under 20, who was recently able to leave the Soviet Union. The influence of the monasteries on the life of the emigration is independent of the number of residents. As religious centers, all monasteries and convents are of particular importance in areas where émigré communities are located at great distances from one another, as for example in Australia, Chile, and Canada. It is precisely in these areas that the monasteries are church centers for pilgrimage and veneration of their shrines.

The number of residents says little about the significance of the monastery. This was shown in the example of the St. Herman Monastery at Platina. The Brotherhood had only two monks at first, but the literature published by the Brotherhood was wisely disseminated and played a considerable rôle in the spiritual and religious education of the faithful, predominantly, however, in the mission among the English-speaking population. Thus, the number of inhabitants of the monasteries is quite diverse —from hermitages with one to two inhabitants to average monasteries with five to ten inhabitants, like the St. Job Monastery in Munich, the Annunciation Convent in London, or the Dormition Convent in Chile, up to monasteries with 20-50 inhabitants, eg. Holy Trinity Monastery in Jordanville, the Lesna Convent in France, and the convents in the Holy Land.

The economic basis of the monasteries is often very diverse. Whereas the Mount of Olives Convent in Jerusalem can buy in large life off of its agricultural produce, Holy Trinity Monastery in Jordanville is able to live off of its agricultural produce and publishing house, and the Greek Monastery of the Transfiguration of Christ can subsist on its incense production combined with donations, the other communities must depend financially, to a greater or lesser degree, on the Synod of Bishops and the individual dioceses, on the donations of the faithful and on certain funds for the support of the monasteries. This is in part also the result of the tasks that the monasteries have undertaken. Though the monks and nuns are able to make their own livelihood mostly by agricultural work and handiwork (the manufacture and sale of church utensils, icons and candles) as well as printing presses or book binderies, they need help with the repair of buildings and churches, the upkeep of the grounds, the running of schools, orphanages; homes for the elderly and hospitals. The faithful’s willingness to make donations over the decades has made it possible not only to establish monasteries, to purchase freehold land with buildings but also to subsidize the inhabitants and finance their social, charitable and educational endeavors.

Most monasteries have accommodations for guests, who are always welcome in the monasteries. In accordance with the old tradition, guests’ room and board are provided at no cost. They may, however, support the monastery by making a donation. The course of a day in a monastery follows a routine similar to the following: at 4 A.M. rise from sleep; at 5 A.M. morning prayers and matins; between 7 A.M. – 9 A.M. or so, the Liturgy, followed by communal breakfast; at 12 noon, the midday meal; between 6 P.M. and 7 P.M., vespers, followed by supper; then, at around 8 P.M., compline and evening prayers (as in the morning). [16] There are differences in individual monasteries, cf. Nikon, Zhizneopisanie 5, p. 123. In a few monasteries, such as the St. Job Monastery in Munich, the Athonite rule is followed. Here, the services begin between 2 A.M. and 4 A.M., and last until 8 A.M. The remaining time – some eight to ten hours – is set aside for work, which is done in the monastery’s workshops. During the midday and evening meals, writings from the Church Fathers, the Lives of the Saints, and so forth, are read. All meal times begin and end with a common prayer. The meals consist of vegetables, fruits, bread, and grain dishes (buckwheat, among others), and, at appropriate times, also dairy products. Fish, when it is available, is eaten on feast days and Sundays, not, however, during the fasts. Meat and poultry are forbidden. The main meals consist mostly of cabbage soup, potatoes, bread, and tea. Meals are taken together. In a few monasteries, the residents and guests eat in a common refectory; in others, men and women are separated for the meals. During the divine services, men and women stand separately from one another [Trans., men on the right and women on the left]. The cells of the monks and nuns may be visited only by inhabitants of the monastery, not, however, by visitors. The ordering of the monastery follows the rules for monasteries passed by the Council of Bishops in 1959, which in part follows the ordering of 1853.

In the monasteries, wonderworking icons and relics of the saints and martyrs, which have been brought from Russia, Mt. Athos, the Holy Land, and the old Russian monasteries, are venerated. Many of these icons and relics (for example, the Lesna Icon of the Mother of God or the Wonder-working Vladimir Icon of the Mother of God and the Icon of the God of Sabbaoth) were brought by refugee monks and nuns from Russia. Others were made for the new monasteries by the Athos monks, the monks from the Valaam Monastery, and the convents in Palestine as a present, whereby these old monastic houses expressed their closeness to the new monasteries of the émigrés. The faithful made pilgrimages to these shrines and prayed for protection and assistance. The great significance which is accorded the patron saint of the monastery is evinced when the faithful from afar visit the monastery to celebrate the divine services together with the monks and the nuns.

Before World War II, the following monasteries and convents belonged to the Church Abroad: [17] On the history of the individual monasteries and for more detailed information, cf. Seide, Klöster im Ausland.

Monasteries:

Milkovo Monastery

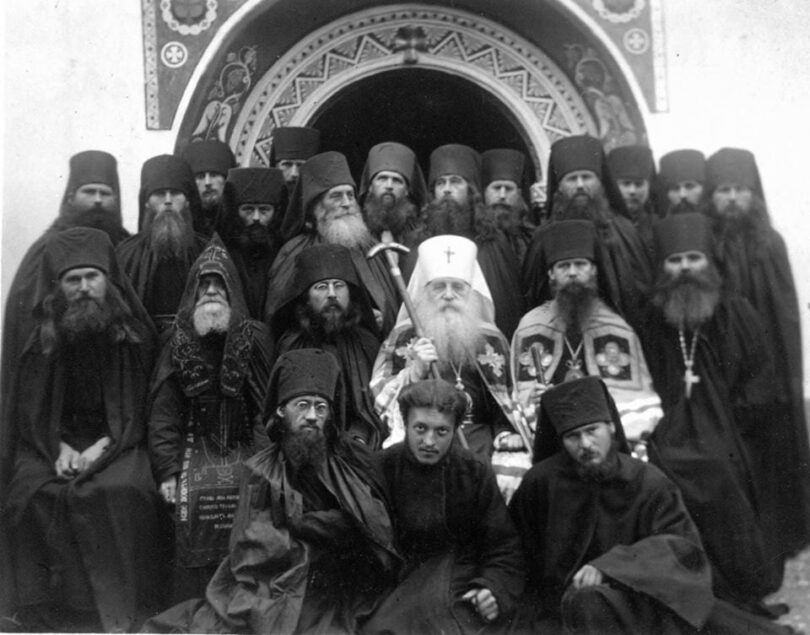

, near Lopovo in Yugoslavia, founded in 1926 by Hieromonk (later Archimandrite) Ambrose (Kurganov). Approximately 20-25 monks belonged to the monastery. Many hierarchs of the Church Abroad, including Bishops Theodosius (Samolovich), [Saint] John (Maximovich), Leontius and Anthony (Bartoshevich), Nikon (Rklitsky), Joasaph (Skorodumov), Savva (Sarachevich), Seraphim (Ivanov) and Tikhon (Troitsky), were very close to this monastery in their younger years. [18] Nikon, Zhizneopisanie 5, pp. 122-128.

Alexander Nevsky Monastery in Stanimaka

(Asenovgrad, Bulgaria). Some twelve monks belonged to the monastery, which supported Bishop Damian’s pastoral school.

St. Job Monastery in Ladomirova

(Eastern Slovakia). The monastery was founded in 1924 by Archimandrite Vitalis (Maximenko, later Archbishop.) Thirty to forty monks belonged to the monastery. The Brotherhood enjoyed widespread respect for its printing press and publishing house. Also, some 20 clergymen were educated in the monastery. The Brotherhood produced Archbishops Vitalis (Maximenko), Vitalis (Ustinov), Seraphim (Ivanov), Nicodemus (Nagaev), Nathaniel (L’vov), Bishop Agapitus (Kryzhanovsky), and others.

Dormition Monastery

in Peking was founded in 1792 and was subject to the Church Abroad from 1920. The monastery belonged to the Peking Ecclesiastical Mission and had two podvoryes. There were 25 monks in the brotherhood, including numerous Chinese, such as the late Bishop Basil (Shuan). The Brotherhood was held in particular respect by the Mission in China for the large quantity of literature it published.

Monastery of Kazan’ Icon of the Mother of God in Harbin

. The monastery was founded in 1922 and had 40 monks in 1939 and as many novices. The Brotherhood deserves particular credit for its social and charitable work, in addition to its publishing work, because the monastery also had a medical center with a clinic, a hospital, and a pharmacy. Out of this Brotherhood likewise came many later bishops, including Bishops Juvenal (Kilin), Basil (Pavlovsky), Nicander (Vintorov, who was consecrated by the Patriarchate), and Metropolitan Philaret (Voznesensky), who belonged to the Brotherhood at the end of the 1950s. [19] Kratky ocherk vozniknoveniya.

St. Tikhon’s Monastery

in the U.S.A. It was founded in 1905 and belonged to the Church Abroad only in the years 1920-26 and 1935-46. In the 1930s, 20-30 monks lived there.

Also subject to the Church Abroad was

the Holy Trinity Monastery

in Jordanville (and two monasteries in Palestine (see below).

Convents:

Convent of the Lesna Icon of the Mother of God

, near Hopovo in Yugoslavia. The convent was reestablished in Yugoslavia by approximately 60 nuns, who had belonged to the convent of the same name in Kholm, which had been founded in 1885. The number of nuns belonging to it remained constant. They deserved credit for the rebirth of Serbian Orthodox women’s monasticism. In the years between the Wars, the convent reestablished some 32 Serbian convents. The nuns also cared for an orphanage attached to the convent, which accommodated 35 children (form 1920-1945, a total of over 500 children). [20] Lesninsky monastyr’; Nikon, Zhizneopisanie 5, pp. 128-130.

Convent of the Protection of the Holy Virgin

, near Knyazhev, in Bulgaria, was founded in the early 1920s, by ca. 10 Russian nuns. They lived by cultivating the land and directed their life entirely to meditation and prayer.

Dormition Convent in Peking

. The convent was founded in the 19th century. Ten nuns belonged to it.

Convent of the Vladimir Icon of the Mother of God

, in Harbin, was founded in 1924 by 20 nuns under the direction of Abbess Rufina. Subject to it were sister convents in Shanghai, Mukden, and Dairen. More than sixty nuns belonged to the sisterhood in the 1930s. They deserve credit for their nursing care of the elderly and for the education of children. In the home for the elderly and the orphanage attached to the convent lived some 150 elderly people, most in need of nursing care, and some 100 children. [21] Svetloi pamyati.

Ein Karem Convent

, in the Holy Land, with some 50-60 nuns, as well as the

Mount of Olives

, and both of the convents in

Gethsemane

and

Bethany

, were subject to the Church Abroad. Some 250 nuns belonged to them (see below).

The Church Abroad lost all of these aforementioned monasteries and convents except Holy Trinity Monastery in Jordanville and the monasteries in the Holy Land when the Communists seized power. The Ein Karem Convent in Israel was given by the Israeli government to the Moscow Patriarchate. St. Tikhon’s Monastery in the U.S.A. joined the North American Metropolia in 1946.

The monasteries and convents of the Russian Church Abroad that exist today were almost all reestablished after World War II, or, like Jordanville’s Holy Trinity Monastery, were built up and extended. Only the convents in the Holy Land remained under the jurisdiction of the Church Abroad.

Monasteries (since 1945)

The Stavropegic Holy Trinity Monastery

Abbot: Archbishop Laurus (Skurla).

Address: Holy Trinity Monastery, Jordanville, New York 13361.

The monastery was founded by the Hieromonk (later Archimandrite) Panteleimon (Nizhnik), and was built up after World War II thanks to an influx of monks from the Ladomirovo St. Job Monastery and the Kazan’ Monastery in Harbin, who joined the brotherhood. At this time, some 35 monks and 7 novices belong to the monastery. The monastery has more than 1,000 acres of land, upon which there are two Russian cemeteries, hostels for pilgrims, and many buildings. Holy Trinity Cathedral, with its many gilt cupolas, forms the focal point of the monastery and has become the landmark of the Church Abroad. The main building contains the monks’ cells, the printing press and publishing house of St. Job, the administrative and financial offices. The Church Abroad’s seminary is located in a spacious adjacent building, which also contains the seminary library, an archive, and a museum. The printing press is of particular importance to the monastery, for it meets all the demands for liturgical and spiritual literature of the Church Abroad today. [22] Bobrov, Troitsky monastyr’.

New Kursk-Root Hermitage

Administrator: Fr. Konstantin Fedoroff.

Address: Russian Orthodox Monastery, P.O. Box Z, Mahopac, New York 10541.

Bishop Seraphim founded the monastery in 1950; it served as the headquarters of the Synod of Bishops until 1957. Today, Bishop Constantine (Essensky) lives in retirement there, and where there is a lay brotherhood, which to a great extent adheres to the order for monasteries with daily services.

St. Herman of Alaska Monastery

Abbot: Hegumen Herman (Podmozensky).

Address: St. Herman of Alaska Monastery, Beegum Road, Box 7 Platina, California 96076.

The monastery was founded in the 1960s and had set as its objective the advancement of missionary work among the English-speaking Americans. Since 1965, the small brotherhood has had its own printing press and has been publishing Orthodox literature in the English-language, which has attained wide distribution and considerable circulation.

Holy Transfiguration Monastery

Abbot: Archimandrite Panteleimon (Metropolis).

Address: Holy Transfiguration Monastery, 278 Warren Street, Brookline, MA 02146.

The monastery was founded at the beginning of the 1960s, by Hieromonk [later Archimandrite] Panteleimon (Metropolis), who had lived briefly in the Russian Monastery of St. Panteleimon on Mt. Athos. This Greek monastery near Boston was the first subject to the Ecumenical Patriarch, then to the Church Abroad in the years 1965-1986. The Brotherhood lived in strict asceticism and follows the Athonite Rule for monasteries. Thirty monks of various nationalities belong to the brotherhood. There are more candidates than places at the monastery. The monastery receives its income from cultivating its land and manufacturing incense.

Holy Transfiguration Monastery

Abbot: Archbishop Vitalis (Ustinov).

Address: Russian Orthodox Monastery, Mansonville, Quebec, R.R. 1, Canada.

This monastery was established in the early 1960s by Archbishop Vitalis’s brotherhood. It is only occupied in the summer because the brotherhood lives at the archpastoral residence in the winter. The brotherhood has a small printing press, in which it prints journals and religious and theological books.

Skete of the Dormition of the Mother of God

Abbot: Hieromonk Seraphim (Filimonoff).

Address: Hieromonk Seraphim Filimonoff, Post Office Northville, Alberta TOE-1, Canada.

The monastery was founded in the mid-1980s and is inhabited by English-speaking Americans. It has a printing press and primarily distributes missionary literature.

Dormition Skete

Abbot: Hieromonk Seraphim (Filimonoff).

Address: Reverend Seraphim Filimonoff, Post Office Northville, Alberta TOE-1, Canada.

The skete was built in 1955-57 and was supposed to be occupied by the St. Job Brotherhood of Archbishop Vitalus. After Bishop Vitalius was appointed ruling bishop of the entire Canadian Diocese, the Brotherhood moved to Montréal and founded the above-named Skete of the Transfiguration. Only Hieromonk Seraphim remained behind. Besides him, two novices and a few lay workers live in the monastery.

St. Nicholas Skete

Address: St. Nicholas Church, Bari, Italy.

The skete was founded in 1952. Hegumen Ambrose headed the skete until the end of the 1960s. Today the skete is unoccupied.

The Monastery of St. Job of Pochaev

Abbot: Bishop Mark (Arndt)

Address: Orthodox Monastery of St. Job, Schirmerweg 78, D-8000 Munich 60, West Germany.

The monastery was founded in 1946 to offer the refugee Brotherhood of St. Job a new home. The Brotherhood consisted of 49 monks in 1945, of which about 30, however, emigrated to the U.S.A., Palestine, France, and South America, because the Munich monastery did not have the financial wherewithall to support such a large brotherhood. Until the mid-1960s, some six monks belonged to the monastery, which ran a small printing press. After the death of Abbot Cornelius, Bishop Nathaniel was appointed abbot of the monastery. Early in 1981, Bishop Mark (Arndt) moved to the monastery and has since become its abbot. A new brotherhood founded by him came with him, and there are now seven members in the community. In 1981, a candle factory and a new printing press were set up in the monastery. Since 1981, the monastery has been directly subject to the German Diocese; formerly, it was subordinated directly to the Synod.

Monastery of the Oak of Mamre and the Holy Forefathers

Abbot: Vacancy.

Address: Hebron, Israel.

The monastery is located in a former hostel for pilgrims near Abraham’s Oak, in the environs of Hebron, and is subject to the Jerusalem Mission. Since the 1920s, a few monks have at all times lived at the monastery; at the present time, there are no monks living there.

Also subject to the Church Abroad in the Holy land is the monastery of St. Chariton, which the Russian Church acquired in the 19th century. Since the 1960s, no monks have lived in the monastery. The members of the Jerusalem Ecclesiastical Mission celebrate the divine services on feast days and commemorative days in the oldest monastery in the Holy Land.

Convents

Novo-Diveevo Stavropegial Convent of the Dormition

Abbess: Nonna.

Address: Russian Orthodox Convent “Novoe Diveevo”, Smith Road, Spring Valley, New York 10977.

The convent was an initiative of Father Adrian Rymarenko, later Archbishop Andrew, to thank for its existence, and was founded in 1948. It was intended to be a place of contemplation and pilgrimage for the faithful near New York. More than forty nuns belonged to the convent at one time. At the present time, some twenty nuns and a few novices live in the convent. The sisterhood succeeded, initially with very modest means, in purchasing 22 hectares over a number of years, upon which they established a cemetery, which at the present time contains 3,600 graves. It has become one of the largest Russian cemeteries in the emigration. In recent years, modern home for the elderly has been opened on monastery land, in which 100 people live. The main service of the nuns, however, has always been, that they take in those without means and émigrés who do not know English.

The Convent of the Vladimir Icon of the Mother of God

Abbess: Ariadna (Michurina).

Address: Russian Convent of Our Lady of Vladimir, 3365 19th Street, San Francisco, California.

In 1948, the convent was reestablished by refugee nuns from the Harbin convent of the same name. The convent also has a skete dedicated to St. Seraphim on the coast of California, some 20 miles from San Francisco. The convent also has a sister convent in Canada (see below), which was founded by nuns from the former Shanghai convent. Twelve nuns belong to the convent in San Francisco. The convent runs a small printing press and primarily publishes religious educational literature.

St. Xenia Skete

Abbess: Nun Brigid.

Address: St. Xenia Skete, Wildwood Rural Branch, Redding, California 96001.

After 1978, when the Fool-for-Christ Blessed Xenia of Petersburg was canonized, a few nuns founded a small sisterhood that was granted the status of a convent. At the present time, four nuns who converted to Orthodoxy belong to the convent, which is located near St. Herman Monastery in Platina. The sisterhood follows the Athonite rule for monasteries. The Divine Liturgy is celebrated in English. The monastery has a small printing press but is currently estranged from the Church Abroad.

Holy Nativity Convent

Abbess: Nun Stephania.

Address: Holy Nativity Convent, 57 Orchard Street, Jamaica Plain, Massachusetts 02130.

This is a Greek convent, which like the aforementioned Greek monastery, was part of the Church Abroad from 1965-1985. In the convent twelve nuns, mostly of Greek and/or American extraction, lived.

Holy Protection Convent

Abbess: Nun Ambrosia (Belomestova).

Address: St. Mary’s Convent, Bluffton, Alberta Canada.

The monastery was founded in 1953, by nuns from the Shanghai convent; others joined in Canada. The nuns live by farming and are subject to the mother convent in San Francisco. The very isolated convent is a place of pilgrimage for many pilgrims from western Canada, who mostly spend several days and weeks in the convent.

Dormition Convent

Abbess: Hegumenia Juliana.

Address: Convento Ruso Orthodoxo, Casilla 14493, Correo 21, Santiago, Chile.

This is the only convent in South America. It is run by nuns who came from the Ein Karem Convent in Palestine, who refused to subject themselves to the Moscow Patriarchate and held true to the Church Abroad. Four nuns and seven novices belong to the convent, as well as a few lay co-workers, who help the nuns in the care of the orphanage containing forty Chilean children, who are all baptized Orthodox. The convent also has a school, which is attended by 100 children.

Convent of the Lesna Icon of the Mother of God

Abbess: Athanasia.

Address: Couvent de la St. Vierge de Lesna, Provement 27150, Etrépagny, France.

The convent was re-established in France in 1950 by 32 nuns from the convent of the same name in Yugoslavia after the Yugoslav authorities granted them an exit visa to the West. From 1950-67, the convent was located in Fourqueux near Paris. After the property, which belonged to the Catholic Church, was purchased, the nuns found a new home in the Chateau of Etrépagny. With the support of the faithful, the nuns were able to obtain the former chateau with an old church and extensive land. Over the years, the convent lost more than twenty nuns, though almost as many have joined the sisterhood, to which today some 30 nuns belong. The monastery is a place of pilgrimage for the faithful from Europe and overseas, who venerate the wonderworking Lesna icon.

Convent of the Annunciation

Abbess: Hegumenia Elizabeth (Ampenov).

Address: Convent of the Holy Annunciation, 26 Brondesbury Park, London NW6, England.

The convent was founded in 1954/59, by the Abbess of the Ein Karem Convent and several other nuns who had left with her. The six nuns arrived in London in 1954 and were finally able to occupy the present house in 1959. The nuns deserve credit for their missionary labors. The monastery is dependent upon financial support because it has no sources of income other than a small bookbindery.

Convent of New Shamordino

Abbess: Hegumenia Eupraxia.

Address: All Saints Convent, 32 Smith Road, Kentlyn, N.S.W. 2560, Australia.

The convent is located in a former monastery, which was never finished. Since 1956, nuns from Harbin have lived there. On the convent’s land are many refugee barracks that were set up for the Russian émigrés from China. Since they left the camp, a home for the elderly has been located on the convent property, for which the nuns care.

Cenobia of the Forerunner St. John the Baptist

This was founded as a monastery by schemamonk Gurius (Demidov) in 1965, and was supposed to be built up into a monastery. These plans failed, because there was no one to occupy it. Today, this coenobium is part of the above convent.

Today, the Church Abroad has some 100 nuns and 50 novices in the Holy Land. Almost all the nuns are Arabs. Nevertheless, these Russian Convents have preserved their Russian character. Russian is the spoken language. The liturgy is celebrated in Church Slavonic.

Russian usages are kept in all monasteries. The Arab nuns are women from Arab Orthodox families who attended the Bethany Convent school or lived there at the boarding school.

The three convents remain under the jurisdiction of the Church Abroad up to the present day because they lie in the Jordanian part of Palestine, and the Jordanian government did not change the property status. The Jerusalem Ecclesiastical Mission spiritually cares for them.

Without exception, the Mission personnel is monastic. The head of the Mission is an archimandrite (at present, Archimandrite Alexis). In the 1930s, more than 20 monks of all ranks belonged to the Mission for a time.

Convent of the Ascension on the Mount of Olives

Abbess: Theodosia (Baranova).

Address: P.O. Box 19-229, Jerusalem, Israel.

The convent was founded at the turn of this century. Before World War I, 100 nuns belonged to the convent; in the 1930s, as many as 200 nuns. Since then, the number of nuns has declined; at the same time, fewer and fewer nuns joined the community. At present, about 50 nuns and 50 novices still live in the monastery — the majority of Arab descent. The convent subsists on its own farming, a candle factory, an icon workshop, and a vestment-sewing workshop.

Gethsemane Convent and Gethsemane Community of the Resurrection of Christ

Abbess of both convents: Barbara (Svetkova), died 1983.

Address: P.O. Box 19-238, Jerusalem, Israel.

Both convents are set in an extensive plot of land in the Garden of Gethsemane. At the center of the monastery is the Church of St. Mary Magdalene with its gilt onion domes, visible on the landscape from afar. A total of 30-40 nuns belong to both convents. A school for girls with a boarding house belongs to the Bethany Convent. The school is attended by 140 girls, half of whom live in the boarding school. Many of the Arab nuns, who live in the Russian convents today, came from this boarding house and school.

References

| ↵1 | There is a 180-page manuscript about the monasteries of the Church Abroad. Regarding the publication of the manuscript, see above, p. XI. [Trans., Monasteries and Convents of the Church Abroad was later published by St. Job of Pochaev Press in Munich in 1990.] For further details, cf. Klöster im Ausland.

Russian monasteries and convents are divided into two major groups: the cenobitic and the hesychyst (anchorites). In cenobitic monasteries, all property belongs directly to the monastery, and the inhabitants are property-less; therefore they are taken care of by the monastery, In hesychyst monasteries, the inhabitants receive free dwelling places and food; clothes, shoes, icons and other things are private property. Of the 1,000 monasteries and convents in pre-revolutionary Russia, 624 were cenobitic (cf. Zybkovets, p.22). The general names for a monastery in Russian are “monastyr” or “obitel’.” There are three different types of monastery: “lavra,” “pustyn’,” and “skete.” Lavra: The title “lavra” means that the monastery has played a significant role in the spiritual and cultural development of the people. In the Russian Empire, there were four monasteries by that name: the Kiev Caves Lavra, the Alexander Nevsky Lavra, the Holy Trinity-St. Sergius Lavra and the Pochaev Lavra. Pustyn’: Hermitage or wilderness monasteries were originally isolated monasteries in the forests or at the edge of the steppes or the desert, which had only had a few inhabitants. Over the course of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, these monasteries attracted many young people who were seeking a solitary way of life. Thus, the number of inhabitants grew sharply. In the Russian Empire there were 74 hermitages for monks and twelve for nuns. Skete: A skete is a small group of hermits or monks dependent upon a monastery, who live in small huts and houses. The elders (senior spiritual leaders among the monks) dwelt mostly in sketes. Stavropegic Monasteries: These are monasteries which do not belong to a diocese, but rather are directly subject to the First Hierarch (in Russia – to the Patriarch; in the Church Abroad to the Metropolitan). The word comes from the Greek “stavros”, meaning “cross”, and “pegnymi”, meaning “I confirm.” It means that the First Hierarch personally consecrates the cross and the antimens, liturgically confirming his authority. Before 1918 there were eight such monasteries in Russia. In the Church Abroad today, Holy Trinity Monastery in Jordanville and Novo-Diveevo Convent in Spring Valley enjoy that status. Until 1981, the Monastery of St. Job in Munich [Trans., and Holy Annunciation Convent in London] also had this status. |

|---|---|

| ↵2 | Seide, Klöster des Patriarchats, pp. 8-17; Tserk. Zhizn’ (1942), pp. 108, 156. |

| ↵3 | From the secret Furov Report, Part 3: “The Monasteries of the Russian Orthodox Church”, German version in “Glaube in der 2-en Welt” (1980), pp. 43-48. |

| ↵4 | Zybkovets, p. 112. |

| ↵5 | Ibid., p. 111. |

| ↵6 | Yearbook of Orthodoxy (1976/1977), pp. 203-204; C. Tarasar, J. Erickson, pp. 102-112 & 302. |

| ↵7 | ”In a Russian Convent” in Glaube in der 2-en Welt (1980) 5, pp. 1-2; ECR (1978) 1-2, p. 153. |

| ↵8 | Manuchina, pp. 563-573. |

| ↵9 | Jahrbuch der Orthodoxie (1976/1977), pp. 171-173. |

| ↵10 | Seraphim, pp. 377-388. |

| ↵11 | Prav. Rus’ (1960) 18, p. 5. |

| ↵12 | N. Schidlovskaya; Z. Frid, pp. 8-12. In 1978 there were 160 Orthodox monasteries in Serbia with 1,100 monks and nuns. The largest monastery is Studnica Monastery with 15 monks; the largest convent is the Ljubostina Convent with 60 nuns, cf. Prav. Rus´ (1978) 11, p. 14. |

| ↵13 | Zybkovets, pp. 196-197. |

| ↵14 | Seraphim, pp. 386-387. |

| ↵15 | Spisok (1980/1981). |

| ↵16 | There are differences in individual monasteries, cf. Nikon, Zhizneopisanie 5, p. 123. |

| ↵17 | On the history of the individual monasteries and for more detailed information, cf. Seide, Klöster im Ausland. |

| ↵18 | Nikon, Zhizneopisanie 5, pp. 122-128. |

| ↵19 | Kratky ocherk vozniknoveniya. |

| ↵20 | Lesninsky monastyr’; Nikon, Zhizneopisanie 5, pp. 128-130. |

| ↵21 | Svetloi pamyati. |

| ↵22 | Bobrov, Troitsky monastyr’. |