Much of this book has necessarily dealt with these particular aspects of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia. Secondly, since the object of the church is the salvation of souls, a parallel strand concerns the jurisdiction’s inner life, which is, ultimately, far and away more important than its outward history. The internal spirituality of a church is its raison d’etre, its “heart” — without which all the rest might seem but a dreary recitation of mere human frailty and hubris.

Thus, while externally the Church Abroad exists on the authority of the famous ukaz of Patriarch Tikhon, on the spiritual level, her heartbeat began and continues on a different plane, in the context of certain mystical events that are seen as guiding the little storm-tossed ship of exiled Russian bishops through the shoals of “the arid sweetness of sectarianism,” [1] Extract from a report to Bishop Hilarion by Consentin des Rosiers, op. cit. in spite of enormous pressures and temptations to the contrary. These “events,” which speak of what is believed to be the Mother of God’s special interest in the Church, are well known to believers throughout the Soviet Union as well as in the diaspora.

The first of these took place on March 3, 1917 (March 16, New Calendar), the day after the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II, when there was revealed, in the midst of dust and ruin, an icon of unknown origin and age, called “The Reigning Mother of God.” A type of icon not seen before, it shows the Mother of God wearing the imperial crown of Russia and other regalia. The faithful immediately recognized this as a revelation that the Saviour’s Mother, “by taking on the imperial regalia… provided hope not only to the legitimate heirs of the Imperial Family, but also to the Russian nation as a whole, that the Orthodox and imperial traditions of Moscow’s destiny as the Third and Final Rome would ultimately win a Christ-granted triumph over the revolutionary atheism.” [2] Ibid. Copies of this icon have been made and distributed throughout the Russian Church Abroad, and are a visible reminder to emigres that their Church exists in order to protect and safeguard a particular ideal — the concept of “Holy Russia.”

Similarly, as has already been noted, the Queen of the Heavenly Host accompanied her believing children into exile by means of the wonder-working Kursk Icon of the “Mother of God of the Sign” — “the Great Hagiatrix of the worldwide emigration” [3] Ibid. — one of the five ancient and most precious icons of Russian Orthodoxy.

And then, unexpectedly, a “third miraculous… icon of the All-Holy Mother of God came forth from the Holy Mountain of Athos, seeking out the hand and hospitality of His Eminence, Metropolitan Vitalii, then still the Archbishop of Montreal.” [4] Ibid. This icon is of the type known as Portaitissa, “Keeper of the Portal.” On November 24, 1982, it began miraculously to exude sweet-smelling myrrh (a special kind of oil used for anointing). “As Metropolitan Vitalii crossed the world bearing this newly-appeared icon… miracles and the flow of myrrh were revealed before the eyes of large numbers of faithful Christians” of all denominations. [5] Ibid. The flow of myrrh continues to this day, completely stopping during Holy Week each year and resuming as soon as the midnight Easter services commence.

It was as if the Mother of God herself, at a time of great and heavy crisis, comforted the afflicted Church and drew the attention of believers to “the one thing needful,” the constant struggle of the soul to find God through repentance, no matter how discouraging outward circumstances might be. Indeed, this ongoing phenomenon of wonderworking icons has had just that effect: bolstering the spiritual life of the faithful, and encouraging the hierarchs to continue walking their special, if much-misunderstood, path.

One of the most difficult steps in that path concerned the 1981 “glorification” (the Orthodox term for canonization) by the Russian Church Abroad of the martyrs of the Soviet yoke (including the Imperial Family) — a difficult step to take because the bishops knew it would draw the scorn and misinterpretations of many outside the Church Abroad. Unlike the Roman Catholic Church, in Orthodoxy the proclamation of sainthood is made by each self-governing Church. The exiled Russian Church, seeing that the Mother Church was not free to grant recognition to those who had suffered martyrdom at the hands of the Communist Party, took seriously its responsibility to openly proclaim that which could only be secretly hoped for behind the Iron Curtain.

Indeed, many private letters and petitions to the Church Abroad had been smuggled out of the Soviet Union asking for the action the émigré bishops now took:

“And behold, that which no one else is able to do, the Council of Eighteen Bishops of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia, as the least part of the whole Church of Russia, has brought to pass, not in its own name, but with fear and trembling, reverently venerating the blood of the martyrs.

We joyously inform you, our brothers and sisters, that in New York City, on Sunday, November 1, 1981, our Council of Bishops glorified with the saints the New Martyrs and confessors of the Church of Russia.” [6] Orthodox Life, (January/February 1982).

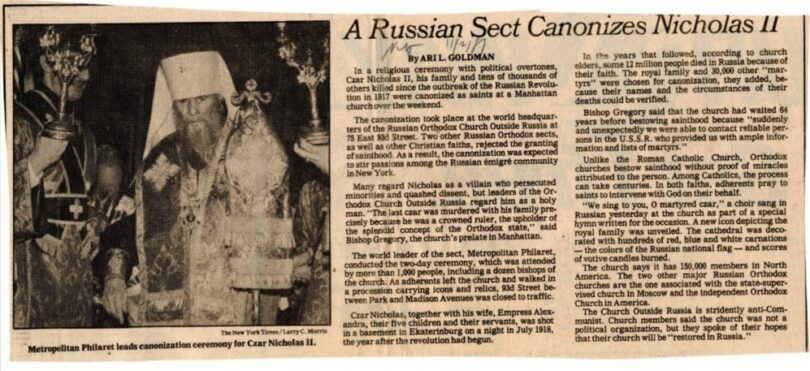

On that day, Park and Madison Avenues near the Synod cathedral were closed to traffic as a mighty procession of more than one thousand of the faithful — which included the Romanov claimant, Grand Duke Vladimir Kirillovich — carrying banners, icons, and relics, proclaimed these New Martyrs to the world. “The cathedral was decorated with hundreds of red, blue, and white carnations (the colors of the [Imperial] Russian national flag) and scores of votive candles burned.” [7] The New York Times, (November 2, 1981). But the New York Times covered the ceremony with a photograph of then-reigning Metropolitan Philaret under the headline “A Russian Sect Canonizes Nicholas II.” [8] Ibid. The National Enquirer, having brought its camera into the incense-laden atmosphere of the cathedral, published a photograph of the assembled prelates in their vestments of deep red velvet trimmed with gold and heavy, bejeweled miters, and trumpeted the headline, “So This Is Manhattan, 1981.” The article characterized the canonization as a “bizarre two-day ritual.” [9] National Enquirer, (November 7, 1981).

If the secular press was more interested in the “exotic” flavor of Byzantine-style church services, critics took this opportunity to titter about how the Church Abroad was still just a collection of disgruntled, exiled monarchists. Needless to say, this was not how the Church saw its action on that day. Prior to the event, the bishops had issued a precisely worded explanation in both Russian and English of the Orthodox meaning of this canonization — and it had nothing to do with politics in the usual sense of the word:

“The Holy Church, glorifying the new-martyrs, says that by their blood she is adorned, as with purple and fine linen — the richest, most beautiful and costly raiment… Great, yea vast is the assembly of the new martyrs of Russia. It is headed by the sacred name of His Holiness, Patriarch Tikhon… At the same time, quite a special place in the company of the new-martyrs is occupied by the Imperial Family, headed by the Tsar-martyr, Emperor Nicholas Alexandrovich, who once said: “If a sacrifice is necessary for the salvation of Russia, I will be that sacrifice.”

Much is now being said of the glorification of the Imperial Family. Many, many of the faithful children of the Orthodox Church — and not only among the Russians — await the day of glorification with joy and impatience. But there are also audible voices of dissent, which speak against the glorification of the Imperial Family. And in the majority of cases, these voices say that the murder of the Imperial Family was a purely political act, that it was not a martyrdom in the sense of dying for the Faith.”

The hierarchs then explained how, and in what way, the massacre of the Romanovs was an actual martyrdom, rather than a political “execution,” concluding that

“…the criminal murder of the Imperial Family was not merely an act of malice and falsehood, not merely an act of political reprisal directed against enemies, but was precisely an act principally of the spiritual annihilation of Russian Orthodoxy… The last tsar was murdered with his family precisely because he was a crowned ruler, the upholder of the splendid concept of the Orthodox state; he was murdered simply because he was an Orthodox tsar; he was murdered for his Orthodoxy!” [10] Orthodox Life, (July/August 1981).

The Russian bishops grasped the inner meaning of what had been forgotten by so many others: that the “lost theocratic splendor” of old Russia had value only because it was a right-believing monarchy “founded not on politics but on religion.” [11] Thubron, Colin, Jerusalem, 1976.

This, then, was the message of the New Martyrs: that God and the True Faith are most important above all else — even for a tsar.

Similarly, Archbishop Antonii of Los Angeles — for many years a vocal champion of the glorification of the Imperial Family — had written in 1979: “The Tsar-Martyr, and his family as well, suffered for Christian piety. He was opposed to the amorality and godlessness of the communists… on principle, because he was a deeply believing Orthodox Christian; by virtue of his position, because he was a staunch Orthodox Monarch. For this he was killed… For this he was removed and slain.” [12] Orthodox Life, (May/June 1979).

Under normal circumstances, the remains of those being canonized are carried in procession. But the only relics of the New Martyrs in existence outside the Soviet Union were those of the Grand Duchess Elizabeth Feodorovna (sister of the Tsarina Alexandra and a granddaughter of Queen Victoria of England) and her attendant, the Nun Barbara. Following the assassination of her husband, Grand Duke Sergei, Elizabeth embraced monastic life and founded the Convent of Martha and Mary, an order which performed works of mercy for the poor. After she and her attendant were martyred, their bodies were eventually taken to the Garden of Gethsemane outside Jerusalem and entombed at the Convent of St. Mary Magdalene. This convent, which is in the hands of the Russian Church Outside Russia, was built by Tsar Alexander III in 1885. It possesses a splendid “Muscovite glamour”: “the White Russian nuns who once peopled the place are mostly dead or aged, but the specter of Holy Tsardom — heady, mystical, irrecoverably gone — pervades the place like incense after them.” [13] Thubron, op. cit.

To prepare for the canonization, the bishops in New York had ordered the opening of the coffins. When this was done, the room was filled with a wonderful aroma, “a strong scent, like honey and jasmine at the same time.” [14] Orthodox Life, (January/February 1982). The body of the Grand Duchess, which was found to be partially incorrupt, was revested and placed in a new coffin with a wax seal, but her right hand was placed in a special reliquary and taken to New York for the glorification ceremony (where it is still venerated by the faithful to this day). Soon after the opening of the coffin, Patriarch Dioddros of Jerusalem and All Palestine came to the convent to pray before the relics, after which he said, “Without doubt, these are holy martyrs and by their prayers may the Lord help the Church of Jerusalem and the Russian Church!” [15] Ibid. (As a side note, it is interesting to see that the Soviets recently allowed the printing of books and articles in the Soviet Union that departed from traditional Communist propaganda concerning Tsar Nicholas II and his family. Some see this as the beginning of a possible rehabilitation of the Imperial Family. In any case, the Synod of Bishops Abroad was clearly prophetic in their recognition of the truth about the last ruling Romanovs.)

Constantly attentive to its inner life and the sanctification of the faithful, the Church Outside Russia also glorified numerous others, both Russian and non-Russian. Some of those especially dear to the Russian people were St. John of Kronstadt, a great evangelical and wonder-working married priest who died in 1908 (canonized in 1964), and the eighteenth-century Fool-for-Christ, Blessed Xenia of Petersburg (canonized in 1978). Dear to both Russians and American converts was St. Herman of Alaska, the humble monk who came with the first Russian mission to North America in the 1790s (canonized in 1970), who is now venerated as the Orthodox Patron Saint of America. In 1980, the bishops also glorified St. Peter the Aleut, an Alaskan native, martyred in San Francisco by Roman Catholics in the early nineteenth century.

One of the more unusual names placed in the calendar of saints was that of Edward the Martyr, the Saxon king whose veneration was confirmed by the Church Abroad in the early 1980s. St. Edward was martyred 979 A.D. at the age of nineteen, and numerous miracles have since occurred through his intercession (and still occur today). During the English Reformation, the fragrant relics were hidden, not to be recovered until 1931, during an archaeological dig by Mr. John Wilson- Claridge on his own family property, where the medieval shrine had once existed in the now-ruined Shaftesbury Abbey.

Since no other church group showed an interest in the relics, in 1979 Mr. Wilson-Claridge offered them to the Russian Church Outside Russia, with the condition that the relics be reverently enshrined. In due course, the Synod of Bishops decreed the writing of a service in the boy-king’s honor (in Slavonic, then translated into English), and the monastic Brotherhood of St. Edward was formed and property was acquired, along with an old Anglican church that was remodeled, at a cost of $100,000, in order to provide a suitable setting for the Edward’s new shrine.

As soon as news of this reached the British public, however, an enormous outcry was heard. Those who had previously shown no veneration for the relics were now indignant that “foreigners” were to possess them (even though the superior of the Brotherhood of St. Edward, and the monastics with him, are all English converts to Orthodoxy). One objector said, “Whatever the case, one hopes that the bones will… not end up in the Russian Orthodox Church in Exile… No Saxon can have deserved that fate.” To which a non-Orthodox venerator of the martyr replied, St. Edward is “as much Orthodox (even if Russian and in exile) as Catholic and Anglican… [and has been provided] a lovely reliquary, shrine, and church to house the relics… No Saxon king deserves better than this, surrounded by undoubting love, honor, and veneration.” [16] Bentley, James, Restless Bones: The Story of Relics, 1985.

Litigation ensued but, at length, the Church High Court decided in favor of the Brotherhood of St. Edward. The case aroused such an interest that James Bentley discussed it in his book, Restless Bones.

Still another heartbeat of the Church Abroad was heard in 1974 regarding the “Old Rite” of the Russian Church. In Russian Church history, the term “Old Ritual” refers to the liturgical books and rubrics used throughout Russia until the middle of the seventeenth century. At that time, Patriarch Nikon of Moscow decided to reform the Rite, bringing it closer, he thought, to the one used by the Greek Church. (Resultingly, the liturgical system used by the Russian Church since the time of Nikon is called the “Received Rite,” or sometimes the “Nikonian Reform.”) Tens of thousands of pious believers refused to accept the reforms and created a great schism (in Russian, raskol). They called themselves “Old Ritualists” or “Old Orthodox,” but the Russian Church referred to them as “Old Believers,” and used the legal arm of the state to persecute them, while at the same time various sobors anathematized both the Old Rite and its adherents.

In the nineteenth century, the Orthodox Church began to move in the direction of correcting the excesses of the past, attempting to heal the schism. This was also discussed at the All-Russian Sobor of 1917- 18. Both Metropolitans Antonii and Anastasii valued and occasionally served in the Old Rite.

Many Old Believers had also gone into exile after the Russian Revolution, forming large communities in several places in North America. Yet there was virtually no contact between them and the Church Abroad. In 1974, at its Third All-Diaspora Sobor, the Church Abroad recognized the old liturgical customs and service books as “Orthodox and salutary,” declared the interdicts and anathemas of the past to be “null and void and rescinded as if they had never been,” and resolved to “permit the use of the Old Rite by those who wish to observe them.” [17] “The Decision of the Council of Bishops of the Russian Church Abroad Concerning the Old Ritual.” (September 25, 1975).

In due time, various communities of Old Believers began to take note. Slowly but surely, contacts began to open up between the Church Abroad and individual followers of the Old Ritual. This historical development is still in process, but in 1983, a very large Old Believer parish in Erie, Pennsylvania, returned to the Orthodox fold via the Church Abroad, in return for which they were given the priesthood and the sacraments (their particular group had been without the priesthood since the 1600s). In 1988, the hierarchs of the Church Outside Russia consecrated their first bishop for the Old Rite — a Russian priest of the Church Abroad who had, as a young man, become a devout practitioner of this title. As “Protector of the Old Rite,” Bishop Daniel (Alexandrov) is in a position to both attract many more Old Believers back to the Church and, at the same time, be a zealous example of the old piety to those using the “Received Rite,” many of whom have become somewhat lukewarm in their piety.

The great event of 1988, however, was the millennial celebration of the Baptism of Russia in the year 988 A.D. Thus Metropolitan Vitalii and numerous bishops and clergy, together with the head of the Russian Imperial Family, Grand Duke Vladimir, gathered at Synod headquarters in New York for a commemorative Liturgy on Sunday, August 7, 1988.

References

| ↵1 | Extract from a report to Bishop Hilarion by Consentin des Rosiers, op. cit. |

|---|---|

| ↵2 | Ibid. |

| ↵3 | Ibid. |

| ↵4 | Ibid. |

| ↵5 | Ibid. |

| ↵6 | Orthodox Life, (January/February 1982). |

| ↵7 | The New York Times, (November 2, 1981). |

| ↵8 | Ibid. |

| ↵9 | National Enquirer, (November 7, 1981). |

| ↵10 | Orthodox Life, (July/August 1981). |

| ↵11 | Thubron, Colin, Jerusalem, 1976. |

| ↵12 | Orthodox Life, (May/June 1979). |

| ↵13 | Thubron, op. cit. |

| ↵14 | Orthodox Life, (January/February 1982). |

| ↵15 | Ibid. |

| ↵16 | Bentley, James, Restless Bones: The Story of Relics, 1985. |

| ↵17 | “The Decision of the Council of Bishops of the Russian Church Abroad Concerning the Old Ritual.” (September 25, 1975). |