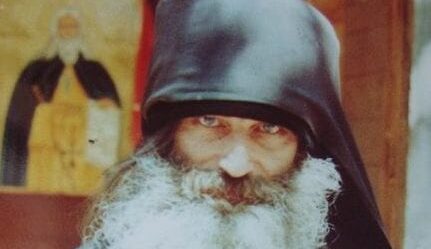

A well-known convert and prolific writer and translator in the Church Abroad, Hieromonk Seraphim (Rose) was particularly interested in the future of Orthodoxy and missionary activity in America. In this, he showed himself a true spiritual son of Blessed Archbishop John (Maximovich) of Western America and San Francisco who, while very much a Russian of the “old school,” nonetheless had a burning desire to bring the light of Orthodoxy into the darkness of the West. (Archbishop John, whose sepulchre in the San Francisco Cathedral of “Our Lady, Joy of All Who Sorrow” is the object of many pilgrimages, has been called “Blessed” since his death in 1966. Although not formally canonized, he is nonetheless regarded as a saint by Orthodox Christians of many jurisdictions.)

Fr. Seraphim saw that if the Orthodox Faith was to take root on the North American continent, as it had a thousand years before in Russia, there must be less emphasis on the external, purely organizational side of Church life and more emphasis on what he called “Orthodoxy of the heart.” The Church in America, divided into so many rival jurisdictions is, he said, in a state of severe crisis — however outwardly successful it might appear. He wrote:

“In recent years, there has been talk once more of American Orthodoxy, and an attempt has begun to end jurisdictional irregularities. In 1960, there was formed a “Standing Conference of Canonical Orthodox Bishops in the Americas,” with representatives from many jurisdictions, with the idea that it would eventually be transformed into the Synod of an American Orthodox Church.

But quite apart from the fact that this “Standing Conference” has not yet resolved some of the jurisdictional conflicts and canonical difficulties among its own members, it has, more importantly, failed even to take cognizance of a basic fact of Orthodox life in America today: Orthodoxy in America has, to a large extent, lost contact with its own roots; it has become diluted and, in some cases, virtually unrecognizable… [and] is well on the way to losing completely its Orthodox character… To some extent, of course, Orthodoxy in America merely shares in the decline of Orthodoxy noticeable in many parts of the world, taking a more acute form here due to minimal contact with genuine Orthodox centers and long exposure to the local heterodox or simply pagan environment.” [1] Orthodox Word, (September/October 1968).

As one who understood and was equally comfortable in both American and Russian cultures, Fr. Seraphim observed that the “acute missionary awareness” of the Church Abroad “cannot be built upon ‘Americanism’ or upon a mere emphasis on the English language; it cannot be built upon [jurisdictional] ‘unity,’ which heretics also possess; it can only be built upon Orthodoxy. True Orthodoxy transcends the barriers of nation and language.” Thus, the existence of the Russian Church Abroad “constitutes an involuntary mission to every continent,” so long as she “upholds the standard of truth for all to see.” [2] Ibid.

Missionary zeal, he said, can flourish “only where there is the awareness of belonging to the one true Church… and of our responsibility to make this infinite treasure known to those outside the Faith for their salvation. Ecumenism, on the other hand, preaches ‘dialogue’ and compromise with those of other faiths, in the name, ultimately, of… human reason — the religion of man.” [3] Ibid.

Analyzing the reason for the Church’s “involuntary exile” and her future, Blessed Archbishop John had written:

“A significant part of the Russians who went abroad belonged to that intellectual class which, in recent times, has lived by the ideas of the West. While belonging to the Orthodox Church… the people of this class, in their world-outlook, significantly departed from Orthodoxy. The chief sin of people of this class was that they did not build their convictions and way of life on the teaching of the Orthodox Faith, but rather strove to make the rules and teaching of the Orthodox Church conform to their own habits and desires. Therefore… they were but very little interested in the essence of Orthodox teaching.” [4] Orthodox Word, (May/June 1973).

This fact, he felt, was the cause of most of the jurisdictional strife among Russians after the Revolution of 1917-18, and is the single most difficult hurdle for the bishops to overcome.

At the same time, Blessed John believed that God had appointed the exiled Russians to perform the task of “shining in the whole world with the light of Orthodoxy, so that other peoples, seeing their good deeds, might glorify our Father Who is in heaven, and thus obtain salvation for themselves.” [5] Ibid. As Fr. Seraphim had also observed: “Divine Providence has dispersed Orthodox Christians throughout the world, not by chance, but to be witnesses of Christian Truth and examples of Christian life. Today, our very existence in non-Orthodox lands is a missionary witness.” [6] Orthodox Word, (March/April 1979).

But, Blessed John warned, if the Russian faithful in the diaspora do not give this witness, “and even abase Orthodoxy by [their] life, the diaspora will have before itself two paths: either to [repent]… and be reborn spiritually; or else to be finally rejected by God and to remain in banishment, persecuted by everyone, until gradually [the Church Abroad] will degenerate and disappear from the face of the Earth.”

This startling prediction — that the exiled Russian Church might have no future at all — a warning given by the revered as “like unto the Holy Fathers of old,” was behind many of the stem instructions to the faithful issued by the bishops on many occasions. Thus, in 1978, Metropolitan Philaret and sixteen other hierarchs cautioned that, while the Church in the Soviet Union has had little or no freedom, nonetheless, even the Church in the West had a great enemy:

“It is not militant atheism or any organized evil, but overabundance and prosperity in freedom. How many of us…has this insidious enemy tom away and continues to tear away from God! Let us not forget…that true freedom is only in God; that there is no freedom in man if he has slain the knowledge of God and buried the very memory of Him. possession of freedom and prosperity places a great responsibility on man… Thus, we call you to faithfulness and steadfastness in Holy Orthodoxy. Be not troubled that more and more often we see ourselves as though abandoned by all. Our path is the path of faithfulness to Christ.” [7] Orthodox Life, (November/December 1978).

The first convert to be raised to the episcopacy in the Church Abroad, Bishop Mark (Arndt), had expanded on this theme on the occasion of his appointment as bishop of Munich and Southern Germany in 1980. He saw that 6migr6s and converts both found themselves

“…in a fog of western ideas, which are fundamentally un-Christian… In dealing with these people, we [bishops] often experience considerable difficulties due, as I see it, to the fact that, to a large extent, we ourselves have not yet adapted to a new approach to those who believe and to those who wish to believe. Life in an un-Christian society and in the neo-pagan world insistently demands such a new approach. Our approach, our actions and ideas, too often reflect the imprint of the historical form of Christianity, when it was a state religion. In our times, different paths must be sought to reach souls thirsting for the true faith of Christ… However, what can we offer to them, the [spiritually] sick; with what can we attract them?… Evidently in this, the supremely important area of pastoral activity, we must act first of all by our personal example. Only through our own struggles can we acquire the spiritual strength to attract people in a constant, conscious striving towards the Kingdom of God. But these personal struggles of a present-day pastor encounter difficulties unknown to pastors of previous centuries.” [8] The Anchor! (September 1987).

As 1988, and, with it, the millennial anniversary of the Baptism of Russia — approached, Metropolitan Vitalii was concerned that while many committees of energetic lay people were organizing all kinds of worthy celebrations, the proper way in which to greet the Jubilee Year was primarily by spiritual preparation. He wrote:

“We do not wish that after such festivities, when gray weekdays inescapably set in, we will again be submerged in our often slack and sickly spiritual life. It is imperatively essential for us to leave a perceptible mark of the millennial anniversary of our baptism on our souls, like a deep spiritual seal on our entire life, and to pass it on to the coming younger generation… May the Lord help us to return, and to turn the whole of our flock to the path of this ancient piety for the millennial jubilee of the Baptism of Russia. Amen.” [9] Orthodox Life, (September/October 1987).

Active missionary work had been especially visible in the Church Abroad since the 1960s, when many English-language mission parishes were founded throughout the United States. As the bishops said in 1978:

“Our situation in the diaspora has drawn to the Church many heterodox who have sought the truth of Orthodoxy and have become faithful children of the Church. And now they are going forth to preach Orthodoxy, principally in the name of our Church…. Thus, by God’s mercy, the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad has outgrown its name and has come to occupy a special, unusual place in the conscience of all Orthodox Christians. Despite our weakness, we have been vouchsafed so great an honor… Without separating ourselves from the Mother Russian Church, our Church is truly the free, multinational, multilingual Church of the diaspora.” [10] Orthodox Life, (November/December 1978).

In 1983, the hierarchs commented further:

“Our Church has been enriched by new children and continues to be enriched not only by Greeks devoted to the faith, but also by parishes tom away [by the Metropolia schism]… and now returning to its bosom… While those of different nationality and previous culture who have joined our Church may sometimes pose one pastoral problem or another, we view this calmly, remembering that before the face of God there is neither Greek nor Jew, Russian, American, or any other sort of distinction according to origin. All are felt to be our beloved children who have a common goal.” [11] Orthodox Life, (November/December 1983).

But active missionary work had been dealt a severe blow from the schism of Fr. Panteleimon and his followers — for more than half of the English-language mission parishes were loyal to him. Although in principle the bishops certainly remained supportive of continued missionary outreach to America, a certain wariness, born of the trauma of the Panteleimonite schism, was now detectable. Immediately after the schism, the Church Abroad enthusiastically immersed itself first in preparations for the thousandth anniversary of the Baptism of Russia, and then in the celebrations themselves. This provided a certain distraction from looking more closely at the serious problems of the near future. But, as new developments in the Soviet Union seemed to reflect a slight softening of the state towards religion, the bishops began to be cautiously hopeful that the Mother Church might yet become free and Holy Russia be resurrected, and this absorbed most of their energy and attention.

Nonetheless, in the years since the Panteleimonite schism, and in spite of preoccupation with political and religious events in the Soviet Union, small pockets of missionary activity, led by convert priests, have continued steadfastly, and most Russian priests are quite open to receiving converts into their parishes.

The subject of the liturgical language, however — in itself not the single most important factor in the Church’s future, but nonetheless a significant one — remains unresolved. In 1983, the bishops had said:

“With the course of time and the growth of new generations, the knowledge of the Russian language and understanding of Church Slavonic [a more ancient form of Russian] is gradually being lost, which calls for the use of the language of the local country. However, the Western languages, which developed outside the Orthodox Church and its culture, cannot always accurately convey the meaning of a number of Slavonic and Greek expressions in the prayers and Scriptures. For this reason, one must value the preservation of the liturgical languages of the Orthodox nations, Slavonic and Greek, as far as that is practically possible…

The Church’s task in this matter is to show tact in gradually permitting services in other languages. Haste in this matter can severely damage the spiritual life of the faithful. In light of this, when the rector senses in his parish the desire of a part of the parishioners to introduce linguistic changes in the services, he must report all circumstances to the diocesan bishop and introduce such changes only with his approval.” [12] Ibid.

While in principle no one disagreed with this decision, it seemed to be somewhat out of touch with reality. In mission parishes, excellent English translations (King James style) had already been used almost exclusively for more than ten years, and in the typical Russian parish only a few still understood the Slavonic language; it was clear that the Church was now running a serious risk of losing a significant part of its younger generation because the divine services were incomprehensible to them.

In February 1986, more than a dozen of the convert clergy — essentially those who had remained faithful to the Church Abroad at the time of the Greek schism — asked for and received a meeting with Metropolitan Vitalii at the Synod in New York. Bishop Hilarion (Kapral), deputy secretary to the Synod, and a few of the Russian clergy also attended. The purpose of the meeting, which lasted all day, was to discuss the implications and impact of the schism, as well as the future of missionary activity in the Church. The Metropolitan, who speaks fluent English, was gracious and receptive, thoughtfully answering all questions put to him, yet very much in command of the situation. Among the concerns expressed was a desire on the part of the convert priests to see a continuing and expanded use of English in the divine services. The Metropolitan indicated that, although he had some reservations about moving too quickly on the matter, it was inevitable in the United States that English would ultimately be the liturgical language of the Church — “perhaps in a hundred years,” he said.

In a lengthy 1978 report entitled “The Liturgical Language of Foreign Converts to Orthodoxy,” then Archbishop Vitalii of Montreal said, “There had not been and is not now an urgent need to perform the divine services in foreign languages,” and that “for the creation of a liturgical language” there must be converts who, with fasting and prayer, “will pour into the words of their own languages the power of the grace of the Holy Spirit from the mystery of their Baptism… rather than some approximate meaning taken from a dictionary by some translator.” In answer to those who asked how to conduct themselves in their worldwide missionary endeavors, he said that it was essential to preach and read from the Scriptures in the local language, “but we must be very, very careful, very cautious in dealing with the liturgical texts. The divine services are our Church’s holy of holies.” He suggested that “we ought very skillfully to introduce into services for foreigners one or two words in their own language or some exclamation and then limit ourselves to that for a long time, until they become prayerfully accustomed to those words, until those words are overshadowed by the power of grace.” He reminded converts that they must imitate Ruth in the Old Testament, who had said “For whither thou goest, I will go; and where thou dwellest, I will dwell; thy people shall be my people, and thy God my God.” [13] Report to Council of Bishops, 1978.

In the spring of 1986, following his meeting with the convert clergy, Metropolitan Vitalii gave the report wide distribution in America, evidently intending that it represent his official view of the subject.

The reaction among the converts in the Church Abroad was less than universally enthusiastic. But since, as was noted above, English was already being used almost exclusively in the mission parishes, either without the Metropolitan’s knowledge or with his tacit approval, it was felt best not to pursue the matter any further and let Church life among the converts proceed along a familiar path. One convert layman, however, was outraged at the Metropolitan’s words, which he exaggeratedly saw as an insult to Americans who had been on the receiving end of what he called “ethnic brutality” for too long. A lengthy article, “The Betrayal of Orthodoxy in America,” concluded with this battle cry, a message that not even the Russian hierarchy of the Church Abroad would disagree with, whatever the lesser issues might be:

“True Orthodox Christians! Together let us take notice that the leaves of the fig tree are drooping. Let us call together as many of us as can be mustered — Russians, Americans, Greeks, and others — and let us pray Our Lord Jesus Christ that He grant us one more year to dig around it, to fertilize it, and to water it unto the refreshment of its foliage and the production of sound fruit, acceptable to Heaven. Even so, Lord, fashion our hearts!” [14] “The Betrayal of Orthodoxy,” unsigned, undated.

All of this signified that the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia — far from being a moribund collection of “exiled monarchists,” as its critics charged, was slowly growing and responding to all kinds of developments in society, as well as in the life of the Church itself. As Fr. Seraphim had once written: “They are wrong who teach that, because the end of the world is at hand, we must sit still, make no great efforts, simply preserving the doctrine that has been handed down to us, and hand it back, like the buried talent of the worthless servant, to our Lord at His Coming!” [15] Orthodox Word, (November/December 1972).

References

| ↵1 | Orthodox Word, (September/October 1968). |

|---|---|

| ↵2 | Ibid. |

| ↵3 | Ibid. |

| ↵4 | Orthodox Word, (May/June 1973). |

| ↵5 | Ibid. |

| ↵6 | Orthodox Word, (March/April 1979). |

| ↵7 | Orthodox Life, (November/December 1978). |

| ↵8 | The Anchor! (September 1987). |

| ↵9 | Orthodox Life, (September/October 1987). |

| ↵10 | Orthodox Life, (November/December 1978). |

| ↵11 | Orthodox Life, (November/December 1983). |

| ↵12 | Ibid. |

| ↵13 | Report to Council of Bishops, 1978. |

| ↵14 | “The Betrayal of Orthodoxy,” unsigned, undated. |

| ↵15 | Orthodox Word, (November/December 1972). |