Archimandrite Aleksei (Chernai) passed away on this day in 1981.

Aleksandr Chernai was born in 1899 into the family of the Kovno (now Kaunas in Lithuania) district court chairman. At the beginning of World War I, Aleksei’s family moved to the town of Luga. Aleksandr attended one of Saint Petersburg’s gymnasiums and served as a subdeacon to Bishop Benjamin (Kazanskii) of Gdov (the future Metropolitan and New Martyr).

During the Civil War, Aleksei enlisted in the North-Western Army of General Nikolai Yudenich. After its defeat, he returned to Kaunas, at that time the capital of Lithuania. In 1925, Metropolitan Elevferii (Bogoiavlenskii) of Lithuania (Moscow Patriarchate) ordained him a priest. Fr. Aleksandr served in various places in Lithuania. He survived both the Soviet and German occupations. In 1944 his bishop Metropolitan Sergii (Voskresenskii) of Vilnus and Lithuania, Exarch of the Baltics was deadly ambushed by the unknown men claded in German uniform. In 1944, his wife Tatiana passed away, and Fr. Aleksandr, with four children, moved westward, going on the same displaced persons route as many others. In 1948, Fr. Aleksandr arrived in the US and served in the Mid-West, Texas, and Mexico. In 1957, he was tonsured a monk and appointed an archimandrite to South Africa.

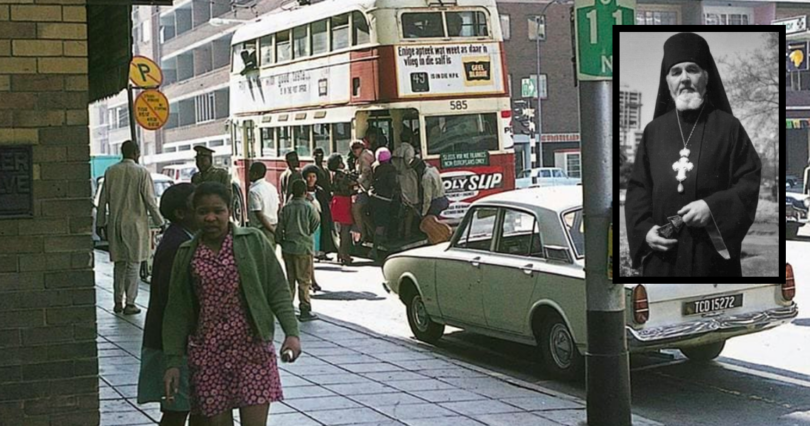

Metropolitan Anastassy tasked Fr. Aleksei with disseminating the Orthodox faith, and this objective ran into the conditions of apartheid (separateness from Afrikaans), deeply rooted in the culture of the Dutch East India Company founded in the early seventeenth century, which colonized the initial territory of the future South African Republic. This was no small challenge. Dmitry P. Anashkin, the scholar of the Russian Church Abroad, explained the dilemma that Fr. Aleksei faced as follows:

“The Russian Church did not conduct any missionary work among native Africans, even though some of them demonstrated a certain interest in the Church. For example, in the Kingdom of Lesotho, a group of Africans formed, calling themselves the ‘Orthodox African Church,’ and petitioned Fr. Aleksei to receive them into the Russian Orthodox Church. One of the members of this group traveled several times to meet Fr. Aleksei and invited him to visit Lesotho. From a missionary point of view, this could have led to positive results, but the SAR government opposed any rapprochement between Russians and native Africans. As Fr. Aleksei was told, several government institutions were categorically opposed to Africans receiving pastoral care from the Russian Church, and it was even implied that should he violate government policy, he might be stripped of his residence permit.”

Moreover, Leonid von Mansyreff, starosta (warden) of the parish of Holy Prince Vladimir, was an editor of the magazine To the Point, which was published with government funds and had a mission to change the negative perception of South Africa in the West. Later, he worked as a consultant at the Defense Ministry.

The Russian community in the SAR was dying out and could not afford to support a priest. Fr. Aleksei’s health deteriorated. In 1974, Fr. Aleksei returned to the USA. He passed away six years later in San Diego. After the downfall of the apartheid regime, the Moscow Patriarchate opened three parishes in South Africa. The history of the ROCOR parish in South Africa during apartheid may serve as a case study for understating the interaction of the communities of the Russian Church Abroad with the non-democratic regimes of the twentieth century.

Sources:

“Arkhimandrit Aleksei Chernai,” Sinodik RPtsZ.

Dmitry P. Anashkin (+2018), “Russian Orthodoxy in South Africa in the 1950s and ’60s,” Historical Studies of the Russian Church Abroad.