Foreword

At the Crucifixion of Our Lord and Saviour, Jesus Christ, all the disciples of the Lord deserted Him. With the exception of Saint Joseph of Arimathea, only the Most Holy Mother of God and the eight Myrrh-Bearing women remained in Jerusalem to care for His Sacred Body. And it was to these holy women, who loved the Lord and never deserted Him, that the glorious news of the Resurrection of the Lord was first announced. It was these holy women who were entrusted to deliver the Good News to the disciples of the Lord. So, at the most sacred moment in the whole divinely-appointed history of the world, it was the women followers of Jesus who remained at the heart of that revelation.

This historical event may be seen as an icon of our life in the Church today. By my observation, women constitute at least seventy per cent of every parish. Moreover, generally, it is the women who follow the example of the holy women who never deserted the Crucified and Resurrected Lord. In any parish, it is generally the women who tend to the well-being of the parish. They cook; they clean; they beautify our temples; they bring flowers; they care for the vestments; they provide sustenance to the parish; they visit the sick; they care for the poor; they chant; they read. And yet, in almost all written accounts of the history of the Church, women are almost invisible. A notable exception is a scholarly history of the London parish of ROCOR by Fr Protodeacon Christopher Birchall: Embassy, Emigrants, and Englishmen (Jordanville: 2014) in which the author intentionally chose to draw attention to the lives of laymen and women of the emigration as well as those of the clergy. In this centenary year of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia (ROCOR), of course, we shall remember our archpastors and pastors who laboured and suffered for the sake of Christ the Saviour and His Church. However, there is a danger that the sacrificial role of women in the Church will be forgotten or, at least, taken for granted.

As a parishioner of the London parish of the ROCOR, I look at the various ROCOR websites almost in vain for a mention of the laity, let alone the women. The focus is almost exclusively on the clergy: women seem to be forgotten. 98% of website content is focused on the activities of the clergy, not the thousands of pious women — and laymen — who comprise what the Holy Apostle Peter calls “the Royal Priesthood.”

But ye are a chosen generation, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, a peculiar people; that ye should shew forth the praises of him who hath called you out of darkness into his marvellous light. (1 Peter 2:9)

Usually the history of the ROCOR is written with almost 100% focus on the (necessarily) male clergy. What a marvellous tribute it would be if, in this centenary year, that history could be written within a framework which eschews clericalism and which recalls the laudable sacrifices made by the women of the ROCOR, especially the hundreds of thousands of refugees who, despite their material poverty and frequently horrific circumstances in war, in exile and in the refugee camps, always offered to the ROCOR the “widow’s mite” (Mark 12:42).

It is in this spirit that we can recall the heroic life and suffering of one daughter of the Russian emigration, Maria Alexeevna Nekludova, who appears to have been all but forgotten by the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia.

Maria Alexeevna Nekludova – A Good Soul

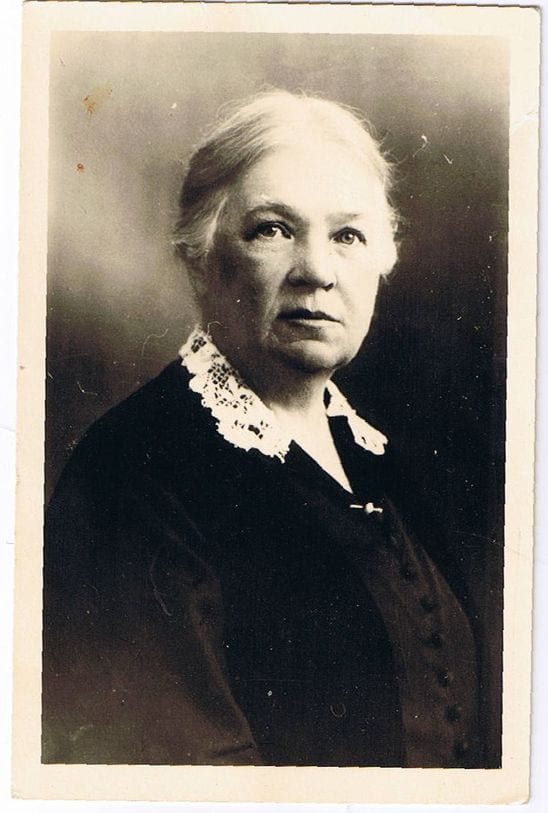

In memory of Maria Alexeevna Nekludova, former director of the Empress Maria Feodorovna Institute for Girls in Kharkov, forcibly repatriated to the USSR by the Soviet authorities in 1945 and sent to live in the remote village of Kuz’kino, Kuibyshev Province, where she died in 1948, aged 82, from exhaustion and lack of medical care. [1]The sources for this paper are: Leonid L. Lazutin, Mariia Alexeevna Nekliudova. http://xxl3.ru/kadeti/nekludova.htm Accessed February, 2020; Andrei Slesarev. Private letters of 26-27.09.2010. … Continue reading

St Petersburg and Kharkov

Born in 1866 in St Petersburg, Maria Alexeevna Nekludova came from a noble family and was educated in the Smolny Institute for Girls in Saint Petersburg. After graduating from the Institute with an award from the Empress for her achievements, she resolved to dedicate her whole life to raising children and joined the same Institute as a teacher. She attracted the attention of the Institute’s leadership through her attentiveness and care for the children, her knowledge of how to approach them, and her assiduous performance of her duties, and was appointed Class Inspector. In 1915 Maria Alexeevna was appointed Director of the prestigious Kharkov Institute for Girls in what is now Ukraine.

On 4th March, 1917, the Provisional Government entrusted the administration of the Institute to the Ministry for State Charity, as a result of which its funding was dramatically reduced. In September 1917, at the orders of the Ministry, the Institute in Kharkov took in pupils from Petrograd (now St. Petersburg). The seizure of power by the Bolsheviks, breakdown of communications with Petrograd (where the Institute’s funding came from) and doubling of the number of pupils and staff had a highly deleterious effect on conditions in the Institute. When in 1917 the local government came to power in Ukraine, the Institute’s situation grew worse still.

However, the Ukrainian Ministry for National Education took a very positive view of the Institute and considered it to be a beneficial institution for the South of Russia, promising to maintain its former status. Then in December 1918, Kharkov was again taken by the Bolsheviks. On 4th January, 1919, the Bolsheviks declared that the Institute was to be liquidated within 3 days. They wanted to send the younger girls from the classes up to year 4 to orphanages and to force the older ones to work. Their orders were expressed in crude terms, for example: “We do not want to support the children of our class enemies for even one more day.” “Previously our children worked for you; now yours will work for us.” However, the Institute’s Director, Maria Alexeevna Nekludova and the Chair of the Parents’ Committee, Doctor Ganʹsheev, took energetic measures to find homes for the girls – about half of whom were orphans – in gentry families or families of civil servants that they knew. The Kharkov Society responded with great energy and within three days almost all the girls had been resettled. Those who were left were sent to the Diocesan School for Women. The Bolsheviks were thus prevented from carrying out their threatened “class revenge”. The Bolsheviks set up a home for orphans in the building of the Institute instead.

On 9th June, 1919, Kharkov witnessed some happy minutes of liberation from the nightmarish tyranny of the Bolsheviks. The city was taken by General Denikin’s army. Maria Alexeevna immediately set about restoring the Institute. With assistance from the Headquarters of the Supreme Commander-in-Chief, the Institute was restored and the building was fully renovated by the beginning of the 1919/1920 academic year. But this happy time did not continue for long. In November, news came of the Bolsheviks’ advance. Many parents quickly pulled their children out of the Institute. On 22nd November, the Institute, after serving a brief farewell Service of Intercession and taking with it only some of its property, Maria Alexeevna left Kharkov in haste with 157 pupils, 38 staff members, and 46 family members of those who had been serving there, without funds and almost without food. This was the beginning of a terrible evacuation on carts, in the midst of all manner of misfortunes and deprivations, and above all in imminent fear of being caught and executed by the Bolsheviks.

Into Exile

After arriving in Novocherkassk, the Kharkov Institute found accommodation in the rooms of the Don Institute. They spent three weeks there and then set out for Ekaterinodar, then Novorossiysk. For three months of the winter, the girls, aged from 8 years upwards, were snowed up in a siding at Novorossiysk in the Caucasus. Peasants gave them presents of food and fuel which kept them alive. In Novorossiysk, Maria Alexeevna visited a certain Mr. Nenadovich, a representative of the Kingdom of Serbia, and reminded him of the Russian connection to the Montenegro Institute (Chernogorskiy Institute), asking him to get in touch with the government in Belgrade with a request to take in the Kharkov Institute as an educational institution during this time of troubles. Several days later, Mr. Nenadovich informed her that they had received an order to issue visas to the Institute for Serbia with transit via Bulgaria.

On 29th January, 1920, the Institute boarded the steamship Afon together with the Don Institute to sail to Varna. A month later, on 29th February, 1920, they arrived in Varna, where they got on a train to Serbia, arriving in Belgrade on 4th March. They were given a former Hungarian school as a permanent home in Novi Bečej (Нови Бечеј) in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. Novi Bečej, a town in the province of Vojvodina, is located some 40 miles from the town of Sremski Karlovci (Сремски Карловци) where in 1921 the headquarters of the Synod of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia had been established.

Novi Bečej

In Novi Bečej funds were provided to support the Institute. Maria Alexeevna was able to find reliable and experienced people to assist her, including Lieutenant-General Zakhar Andreevich Maksheev, former director of the First Cadet Corps, who was employed as Class Inspector, and Senator Alexander Nikolaevich Neverov, who served as a general administrator. In addition to them, she found qualified teaching staff and educators.

Teaching staff of the Institute ca. 1922-1923. M. A. Nekludova (front center). At her left: Lt. General Zakharii Andreevich Maksheev.

There was a need to find clothing and shoes for the children, since their clothing and footwear had become very worn over the course of the never-ending evacuations. Maria Alexeevna issued many appeals for help during this time, with a firm belief that good people would respond. She was not wrong: donations began to flow in and people began bringing and sending in money and items. They acquired sewing machines and musical instruments (grand and upright pianos). The girls were soon dressed in class uniforms just as they had been in Russia. The curricula of the Russian schools that had been evacuated were expanded to eight years, with the right to confer general certificates of secondary education on school leavers, enabling them to enter university.

Great attention was paid to the children’s physical development and health. The Institute had its own hospital and an experienced Russian doctor. In the event of complicated illnesses, doctors were called out from Belgrade, and if surgery was required, patients would be sent to the Russian hospital in Pančhevo (Панчево). The Institute had an excellent library with 10,000 books, classes in drawing, music, handiworks and gymnastics. with skilled teaching personnel. The only thing that it lacked was a chapel, and the children attended a Serbian church instead, taking turns by classes because they could not all fit in the church at the same time along with the Serbian parishioners.

With appointment of a priest, Fr Flor Zholtkevich (d. 1975), who had arrived from Manchuria, in 1926 the Institute opened its own church. The Russian choir’s harmonious singing began to attract people to the church, and not only from the Russian colony, but Serbs, too. In other words, the Institute was a kind of Russian enclave, cast off in faraway Serbia.

Maria Alexeevna did not leave her children without entertainment. Russian-style evenings were organized, along with concerts of vocal music, plays, a traditional Christmas tree with Ded-Moroz (Father Frost) and during Lent there were spiritual talks on Sundays. Metropolitan Antony Khrapovitskii, First Hierarch of the ROCOR (d. 1936), and Hieromonk Ioann Shahovskoi (later Archbishop; d. 1989) visited the Institute from time to time.

Each year around the time of final examinations, the Ministry of Education would send a delegate to inspect the state of education in all the year groups, who would then be present at the examinations and sign the girls’ the school-leaving certificates in his own hand. On the whole, the Russian girls were able to cope with the expanded curriculum and had no trouble being accepted into Serbian universities. Some, at their own desire, were sent to France, Belgium or England to improve their foreign-language proficiency, knowledge of stenography, and so on. After they graduated from the Institute, not one of the girls was forgotten by Maria Alexeevna and her formers pupils were able to ask her for help in times of hardship as they would their own mother.

Then the happy days of the Institute in Novi Bečej came to an end. Due to austerity measures, Russian institutions of education began to be closed down, and this came to pass with the Kharkov Institute. The Institute was merged with the Don Institute in 1932. This was a huge blow for Maria Alexeevna. Despite concerted efforts by city officials to save it, the Institute was closed and Maria Alexeevna was pensioned from then until she moved to Belgrade to assume her new position in 1935 at the age of 69.

Belgrade

In spite of the move to Belgrade and the closing of the Institute and loss of its property, Maria Alexeevna’s spirits did not sink. She was entrusted with running a student residence for 50 girls, mainly the daughters of aristocratic Russian émigrés, known as the ‘Society for the Assistance to Former Pupils of the Kharkov Institute of the Empress Maria Feodorovna of Russia’. Many of the residents were orphans. Again, she faced cares and concerns about how to fit out the residence, about monitoring the behaviour of these grown-up girls and protecting them from bad influences. She shared their joys and their sorrows with them. Like a loving mother, she would give them her blessing to start families and was genuinely glad for them in doing so. Each of her students felt free to come visit her and discuss her life problems and her difficulties and successes in her studies over a cup of tea.

In 1938, Maria Alexeevna made contact with Archimandrite Nicholas Gibbes (d. 1963) in London and subsequently arranged for 10 of her young Russian students to travel to London in April, 1939 in order to improve their English and to sing in English in a church choir organized by Fr Nicholas. The present writer is preparing a paper currently which explores the intriguing story of the “Belgrade Nightingales.”

But upon great people the Lord sends equally great trials. At the time of Pascha in1941 there occurred the German bombardment of Belgrade. Huge stone constructions collapsed like houses of cards, and fires raged everywhere. One bomb fell not far from the building of the student residence. All the windows were blown out by the blast and the plasterwork came down. Maria Alexeevna remained courageously at her post and in so doing brought calm to those under her care.

After this, the Germans occupied Belgrade. There was chaos and uncertainty all around, yet Maria Alexeevna was full of concerns about how to put the residence hall back in order after the bombing. With her excellent knowledge of German, she prevented German soldiers from being quartered in the building, organized the necessary repairs, and provided refuge to a great number of Russian refugees.

Around this time, a Russian Corps for the fight against the Bolsheviks was formed in Yugoslavia, primarily from former members of Wrangel’s Volunteer Army. The Germans used these Russian forces in their operations against Tito’s communist partisans. Many died heroically in this struggle, leaving behind orphaned children. Maria Alexeevna did not forsake them, either, and, from 1942 onwards, the residence hall began to fill up with little boys.

The critical year of 1944 came around. The onslaught of the communist partisans intensified and rumours began to spread that the Red Army was advancing into Yugoslavia. The Germans began to be evacuated while the Soviet Army drew nearer to Belgrade.

Forced “Repatriation”

Maria Alexeevna, in a desire to rescue the children under her care from the horrors of war, resolved to take them to Switzerland but never made it there in the end. Maria Alexeevna and her Institute subsequently made it all the way to Rügen and thence to Annaberg, Saxony Germany. A number of Russian schools were joined together in Annaberg and Maria Alexeevna was head of all of them until the Germans capitulated in 1945. With the Germans defeated, the Soviet Army took Berlin. The war was over, but the real trials for the Russian refugees were only just beginning. According to the 1945 Yalta Accord between Stalin, the British and the Americans, a nightmarish, historically unprecedented forced repatriation of Russians into the heart of Stalinist Russia took place. [2] See Nikolai Tolstoy, Victims of Yalta (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1977). Among those repatriated were Maria Alexeevna and 83 children aged from 2 years to 16 years, even though this was in and of itself a violation of the same shameful Yalta agreement, which only concerned Soviet citizens. Neither Maria Alexeevna nor the children of the Russian Corps soldiers were Soviet citizens, nor could they ever have been. They were sent to the USSR via Kiev all the way to far-away Kuibyshev Province, to the remote village of Kuzʹkino in Novodevichii District.

After the convoy arrived, the children were put up in the building of a church in which the holy images had been covered over with plaster. The Soviet authorities showed no care for the children. The villagers, who were themselves poor, could not provide them with sufficient nourishment. Maria Alexeevna, nearly 80 years old, and the children dug beds, planted vegetables and potatoes, and gathered berries, mushrooms, and nuts in the woods. Thus 2-3 years of hungry life in the Soviet Union went by. At the insistence of the American and the English, as well as Tito’s government, some of the children were sent back to their parents.

Maria Alexeevna asked the Soviets for permission to travel to Leningrad (St Petersburg), where she hoped to find relatives or acquaintances. However, Moscow did not reply to her petition. Her nieces and nephews in Belgrade finally obtained permission for her to return to Yugoslavia, but the Soviets did not give her permission to travel.

The Bolsheviks began to take away the children aged 12 or older and place them in trade schools, while Maria Alexeevna found accommodation in a shoemaker’s shack, where she looked after the children and sewed and mended clothing.

Letters of Maria Alexeevna reached Belgrade. She was, as always, calm and her sole complaint was that there was no church in the village and, over the course of three years, the villagers had only once driven her to a church over 20 miles away from Kuzʹkino — at Pascha. One of her nieces who was living in Leningrad (St Petersburg) would send her 200 roubles per month.

But there was no doctor in Kuzʹkino and the strength of Maria Alexeevna had begun to fade. She had no shoes and thus was forced to wear slippers she had sewn together from bits of old cloth. She was robbed of her valuables and died from a cold and all manner of deprivations.

Tragically, the exact date of her repose appears not to be recorded. She was buried in the autumn of 1948, without a priest of course. However, 2-3 months later, a priest did come to serve a funeral service over her grave and sent a handful of earth from there to her niece in Leningrad, who placed it on the tombstone of the mother of Maria Alexeevna. Thus “great Stalin, the father of the people” thanked this Russian woman for her 80 years of selfless work in bringing up and educating Russian children.

Maria Alexeevna was a good soul and a bride of Christ.

May her memory be eternal!

Acknowledgements

I am deeply grateful to four people for their help in writing this paper:

- Archpriest Stephen Platt, who has given me unlimited access to the archive of Archimandrite Nicholas Gibbes held by his Parish of St Nicholas, Oxford. It was in those papers that I first encountered the heroic personality of Maria Alexeevna Nekludova.

- Professor Leonid L. Lazutin, Doctor of Physical & Mathematical Sciences, Moscow, whose Russian-language webpages preserve the memory of Maria Alexeevna, and who graciously granted me permission to reproduce his materials in English.

- Walker Thompson of the Slavic Institute, University of Heidelberg, Germany, who diligently translated for me from Russian to English portions of Professor Lazutin’s website and who most generously contributed to my research.

- Associate Professor Deacon Andrei Psarev of Jordanville, New York, who also very kindly contributed to my research.

References

| ↵1 | The sources for this paper are: Leonid L. Lazutin, Mariia Alexeevna Nekliudova. http://xxl3.ru/kadeti/nekludova.htm Accessed February, 2020; Andrei Slesarev. Private letters of 26-27.09.2010. Published at http://xxl3.ru/kadeti/nekludova.htm Accessed February, 2020; Kratkii Istoricheskii Ocherk Kharkovskogo Devichʹego Instituta (1927 g.) (A Brief History of the Kharkov Institute for Girls). State Archive of the Russian Federation (GARF), Coll. 6792, Census 2., Doc. 387. Transcription at http://xxl3.ru/kadeti/nekludova.htm Accessed February, 2020; Ksenia Mikhailovna Miller (Antich). Private letters of 23.06.2011 and 08.2011. Published at http://xxl3.ru/kadeti/nekludova.htm Accessed February, 2020; Mitred Archpriest Flor Zholtkevich, Pamiati M. A. Nekliudovoi (To the Memory of M. A. Nekludova), (New York, USA, Novoe Russkoe Slovo (The New Russian Word), 20.11.1952.) Fr Flor (b. 1884) had become a priest before the Revolution and subsequently served in Manchuria. He moved to Serbia in 1926 where he became priest and teacher of Religious Education at the Kharkov Girl’s Institute in Novi Bečej. In 1945 Archpriest Flor went to Vienna and then in 1949 he emigrated to Valencia, Venezuela where he died in 1975; N. N. Ablazhey, Puteshestvie v Kuz’kino: istoriya detei russkikh emigrantov iz Yugoslavii, vyvezennykh v SSSR posle Vtoroi mirovoi voiny (Journey to Kuzkino: a history of the children of Russian emigrants from Yugoslavia removed to the USSR after the World War II). Accessed February, 2020. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/3ec1/13d0bd4fb11db381281977839a16645c59bf.pdf . |

|---|---|

| ↵2 | See Nikolai Tolstoy, Victims of Yalta (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1977). |

With great interest I have read this article. My wife, born Maria Kirillovna Nekludova, was the daughter of Kirill Petrovich Nekludov, the nephew of Maria Alekseevna Nekludova.

Al the photos and documents relating to M.A. Nekludova, which were in our possession, were given to the Dom Russkogo Zarubezhia in Moscow.

Dear Dr Dr Nikita Tregubov,

Thank you for your most interesting information. I wonder if those papers record the exact date on which Maria Alexeevna reposed in the Lord?

Nicolas Mabin.

Dear Mr. Mabin,

The date of death of Maria Alexeevna was listed 28 December 1948.

Sincerely

Dr. Nikita S. Tregubov

Thank you for your wonderful article about my great aunt. My grandmother, Elizabeth Nekludov Folkert, was Maria Alekseevna’s brother’s daughter. Elizabeth fled with the group from Kharkov along with her widowed mother, also named Elizabeth. Peter Alekseevich Nekludov was murdered by bandits in May 1919 near Novorossiysk.

– Maria Sadovnikov Casey

You also mention that “Maria Alexeevna left Kharkov in haste with 157 pupils, 38 staff members, and 46 family members”. I had been under the impression that the only family members who left were my grandmother and her brother and their widowed mother, wife of Maria’s brother, Peter. Do you have any more information on who the rest of these people were? It would be interesting to learn I have more relatives. Thank you – Maria Sadovnikov Casey

Dear Maria Sadovnikov Casey,

Thank you for your kind comments on the article.

The sentence actually reads “and 46 family members of those who had been serving there…” The 46 were relatives of the 38 staff members. Apologies for any confusion in this regard.

Nicolas Mabin.

I see. Thank you. One more question, if I may ask. The article states: “One of her nieces who was living in Leningrad (St Petersburg) would send her 200 roubles per month”. Do you have any information of who this was? Is this the older daughter of Peter, her brother? My grandmother lost touch with her after the revolution and we thought she had perished along with her husband. We would love to be able to clear up a family mystery. Thank you, again.

Powerful, inspiring story — thank you.