“Wherever we had been, we left last, doing our work to the bitter end with unfailing resolve, in the knowledge that our cause was that of the triumph of Christ… We went with the people, yet again leaving our native lands, leaving behind victims who fell under the bullets of partisans and Gestapo agents alike or who simply resolved not to leave or could not leave in time. We went Westward, knowing that we could not expect any mercy from the Bolsheviks, knowing the Soviet regime just as well as the German one this time around. We often heard our hearts saying: stay here, share in the fate of those who have taken up the cross of martyrdom, who are suffering for Christ in exile and concentration camps in the boundless expanses of Siberia. But yet another voice was calling us Westward, saying that that’s not all there is, and that they know the truth in the West and will be able to stand up for the truth.” [1] Benigsen, Georgii, Archpriest. “Khristos-pobeditel’” [“Christ Victor”], in: Vestnik Russkogo Khristianskogo Dvizheniia 168 (1993), pp. 138–139.

These are the words of Priest Georgii Benigsen, who left Latvia forever in 1944. Under Communism, the names of Orthodox clergymen who left Latvia with the retreat of the Fascist German forces, were consigned to total oblivion, and Soviet historiography referred to them with epithets such as “servitors of the Fascist German occupiers” or “utter reactionaries who were closely linked with Hitler’s regime”. [2] Z. Balevics, Pareizticīgo baznīca Latvijā (Rīga, 1987) 135, 139. It is interesting to consider why they left for other countries and their first steps outside Latvia.

In mid-July 1944, the Red Army set foot on Latvian soil. On July 30, sections of the First Baltic Front, which had taken Jelgava, Dobele, and Tukums after much hard fighting, reached the Gulf of Riga. The Fascist German forces were on the retreat in Courland and further to the West. Along with the divisions of the Wehrmacht, the civilian population was also leaving Latvia, as they did not wish to end up under the Communist regime once again. The Latvian Orthodox clergy were faced with a dilemma: either to remain in their homeland under the totalitarian Soviet regime, whose attitude toward religion and the Church they knew well from 1940–1941, or to depart for terra incognita, to foreign parts. Understanding the complexity of this decision, the diocesan administration did not issue any formal pronouncements on this account, allowing each priest to decide concerning his own fate.

The émigrés left in various ways. In some particular cases, priests were forced to do so against their will. According to a decree issued by the Reichskommissariat Ostland, in the event that German forces were to evacuated from the Baltic, it would be “necessary to assure that the Orthodox clergy, especially high-ranking clergymen, not be left behind, lest the Soviets should use them for the purposes of propaganda”. [3] Quoted in: Mikhail Shkarovskii, Tserkov’ zovet k zashite Rodiny. Religioznaia zhizn’ Leningrada i Severo-Zapada v gody Velikoi Otechestvennoi voiny. Saint Petersburg, 2005. p. 208. In August 1944, the Nazis transported Metropolitan Augustīns (Pētersons) to Germany. [4]Metropolitan Augustīns of Riga and All Latvia (secular name: Augustīns Pētersons, 17.02.1873 – 07.10.1955) was born into a peasant family. After graduating from Riga Theological Seminary, he … Continue reading In his words, “in autumn [early August — A.G.] 1944, Gestapo agents came to me and ordered me to travel to Germany. My departure was so rushed that I wasn’t able to grab my mitre, vestments, and church literature.[5]“Metropolīts Augustīns Felbahā”, in: Latviešu Vēstnesis. 1946. g. 27 jūl. At this time, Metropolitan Augustīns Pētersons’ son, captain Georgis Pētersons of the SS Latvian legion, was … Continue reading As Augustīns had been suspended from sacred ministry in June 15, 1942, none of the Orthodox priests accompanied the disgraced Metropolitan when he was evacuated. Archpriest Nikolajs Vieglais was summoned by the Sicherheitsdienst in September 1944, where he was informed that he had to be prepared to proceed to Liepāja along with the Tikhvin Icon of the Mother of God. Father Nikolajs did not want to leave Riga and he was “forced” to leave. [6] Three Orthodox Christian Priests From Latvia. Interviews with Archpriest Nikolajs Vieglais. Petaluma, California, 2006. pp. 50-51. In actual fact, the Nazis were not concerned with the safety and the future of the clergy, and they were thus evacuated only very rarely. Evacuation to the West (or, rather, emigration, since nobody doubted that Nazi Germany’s days were numbered) was generally voluntary.

The largest group of Orthodox clergy, which included Archpriest Nikolajs Vieglais, too, were those who accompanied their ruling bishop, Bishop John (Garklāvs) of Riga, [7]John (Jānis Garklāvs, 26.08.1898–11.04.1982) was born into a peasant family. From 1907–1912, he was a pupil at the church school in Limbaži. In 1915, he joined the Riflemen’s regiment as a … Continue reading who brought the Tikhvin Icon of the Mother of God with them. In the words of the Bishop’s adoptive son, Archpriest Sergii Garklāvs, “the German authorities gave Bishop John twenty-four hours to leave Riga in September 194. He really wanted to stay in Riga, but the authorities could not be persuaded. There were other circumstances, as well. Staying would have meant condemning oneself to inevitable suffering, whereas leaving granted at least some degree of security.” Bishop John, therefore, submitted to the decree of the occupying authorities and the dictates of his conscience, and “…packed some of his possessions, and left Riga with his mother and personal secretary Sergii and set out for the port of Liepāja”.[8]L. A. Kolesnikova, Archpriest Alexander Garklāvs, Tikhvinskaia ikona Bozhiei materi. Vozvrashchenie. [The Tikhvin Icon of the Mother of God. The Return.] Saint Petersburg, 2004. pp. 62–63. According to the testimony of Archimandrite Kirill (Nachis), who met Bishop John in Liepāja, “…Vladyka John did not want to leave his native land, saying, ‘Why would I go there, who and what will I be there?’”, and he expressed a desire to remain in Latvia and, somehow, to avoid being evacuated. Vladyka wanted to hide the icon and not to go anywhere, all the more so seeing as Courland was completely encircled by Soviet forces at the time. However, circumstances and the fate of the holy image and those escorting it turned out otherwise.” [9]Archim Kyrill Nachis, “Narod zhazhdal molit’sia, zhazhdal pokaianiia…” [“The People Were Thirsting for Prayer, Thirsting for Repentance…”], in: Sankt-Peterburgskie … Continue reading In Liepāja, the group of Bishop John grew to over 30 people. It included Priest Nikolajs Vieglais, Fr. Nikolai Perekhval’skii, Fr. John Baumanis, Frs. Viktor and Arsenii Koliberskii, Fr. Ioann Legkii, Fr. Feodor Mikhailov, Fr. Alexei Ionov, and others.

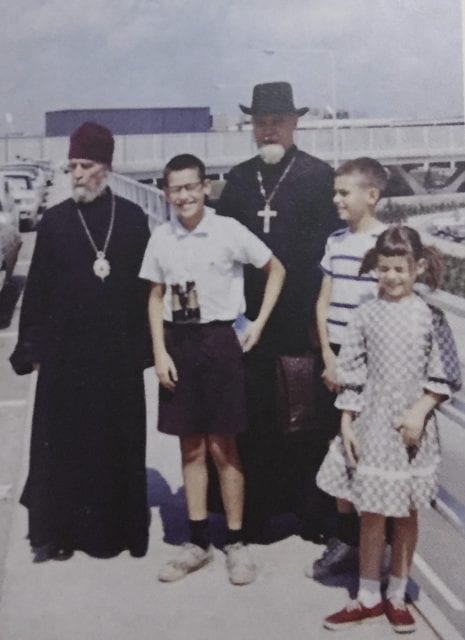

Bishop John at the patronal feast in a DP camp in Regensburg, 1947. Photo: A.Gavrlii, Pod pokrovom Tikhvinskoi ikony, Tikhvin, 2009.

By all accounts, the evacuation of the clergy was not tightly controlled, as one of the priests, Fr. Nikolai Trubetskoi, managed to avoid being evacuated at the last moment and to stay in Latvia. He subsequently paid a dear price for his love for his homeland. On October 20, 1944, Fr. Nikolai Trubetskoi was arrested by the NKVD and sentenced to 10 years in the camps. His fate was by no means exceptional, since one out of four priests in Latvia faced persecution by the NKVD in the years after the war. [10]Golikov, Andrei, Priest, and Fomin, S. Krov’iu ubelennye. Mucheniki i ispovedniki Severo-Zapada Rossii i Pribaltiki [Whitened by Blood. Martyrs and Confessors of North-western Russia and the … Continue reading

On September 22, 1944, Bishop John’s group was loaded onto a transport ship headed for Danzig (now Gdańsk). From Danzig, Bishop John and the priests accompanying him travelled to the Czech city of Jablonec. They were in Czechoslovakia when World War II ended and, as a result, found themselves in the Soviet zone of occupation. Fearing that they might be forcibly deported to the USSR and consequently persecuted by the NKVD, the Latvian refugees began looking for an opportunity to get to the American zone of occupation. In August 1945, they travelled to Prague, where they met up with a group consisting of clergy and laity from the Diocese of Lithuania, headed by Archbishop Daniil (Iuzv’iuk) of Kaunas. [11]Daniil (Nikolai Porfirievich Iuzv’iuk, 02.10.1880–27.08.1965) graduated from Vilnius Theological Academy, and taught at Vilnius Theological Seminary from 1925–1939. From 1939 onwards, he … Continue reading Yielding to the propaganda of the Soviet Repatriation Commission, Archbishop Daniil returned to the USSR, where he paid dearly for his gullibility, in the form of a four-year prison sentence.

With help of Bishop Sergii (Korolev, 1881–1952), the administrator of the Evlogian parishes in Czechoslovakia, Bishop Ioann (Garklāvs) managed to secure the support of Caritas, the Roman Catholic charitable organizatio,n and thereby saved the members of his group from being handed over to the Soviet Union. Joining a group of Belgian and French refugees, the Latvian priests, disguised as Belgian laborers, were able to cross the border with Czechoslovakia and get to the American zone of occupation – initially to the Czech city of Pilsen, and thence to the small town of Amberg near Nuremberg, West Germany. Afterwards, Bishop John and his closest entourage came to the displaced persons (DP) camp in Hersbruck, which became a center of sorts for émigrés from the Baltic countries. Bishop John remained in Hersbruck until he left for America in 1949.[12]Three Orthodox Christian Priests From Latvia. Interviews with Archpriest Nikolajs Vieglais. Petaluma, California, 2006. p. 56.

On February 11, 1945, the Yalta Agreement, featuring secret arrangements for the return of displaced persons, was signed by the Allied Powers. These arrangements stipulated that “all Soviet citizens would be held in camps or collection points until such a moment as they would be handed over to… the Soviet authorities”. Moreover, it was emphasized that “after [their] Soviet citizenship is established… displaced persons will be repatriated without respect to their personal preferences.”[13]P. M. Vunduka, “Deistviia MKKK v zashchitu bezhentsev i peremeshchennykh lits” [“Actions of the International Red Cross to Protect Refugees and Displacd Persons”], in: Mezhdunarodnoe … Continue reading The DP camps were created after the end of the war on the basis of these arrangements. By the end of World War II, there were around 7 million people in Western Europe who had been displaced from the USSR since the beginning of the war, that is, September 1, 1939. The Yalta Conference provided the basis for the repatriation of around 5 million people to the USSR by late 1945. It ought to be noted that the Western powers, being guided by the fact that the Baltic countries were not part of the USSR at the beginning of World War II, did not consider refugees from the Baltic to be Soviet citizens and did not forcibly repatriate them.

At an NKVD consultation as early as April 1945, Lavrenti Beria warned the agents who would be in charge of repatriation after the war that they would be “dealing with people who had betrayed their Motherland, and in this respect there is no difference between prisoners of war, deportees, or those who had left of their own will”. The NKVD deemed it necessary to bring them all back to the USSR, since “each of them, if allowed to remain in the hands of the enemies of the USSR, could bring about more harm than a thousand saboteurs inside the country”. [14]Nitoburg, E. L. “U istokov russkoi diaspory v SShA: Tret’ia volna” [“On the Origins of the Russian Diaspora in the USA: The Third Wave”], in: SShA – Kanada: Ekonomika. Politika. … Continue reading A year later, the Soviet government enshrined the NKVD’s position in law and expanded the set of people who were to be repatriated. On June 14, 1946, the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR adopted a decree “On the Restoration of USSR Citizenship to Subjects of the Former Russian Empire, as well as to Persons who Have Lost their Soviet Citizenship”, according to which all émigrés from the former Russian Empire, irrespective of nationality, were subject to repatriation to the USSR. Overall, the mass repatriation of former prisoners of war and civilians went on until January 1, 1952.

Hundreds of thousands of former prisoners of war, “Ostarbeiter”, refugees and evacuees, and members of armed anti-Soviet formations found refuge in DP camps. Apart from struggling to survive, all the displaced persons were worried about being deported to the USSR, which for many of them meant probable death. As Fr. Georgii Benigsen put it: “Like beasts of prey, the members of the Soviet repatriation committees prowl the zones of occupation in search of unfortunate victims. The poor Russian people prefer suicide to being returned to their homeland. Hunted down and frightened half to death, they roam from place to place, not knowing what tomorrow holds in store for them, and not seeing friends or protectors anywhere.”[15][ref]Archpriest Georgii Benigsen, “Khristos-pobeditel’” [“Christ Victor”], in: Vestnik Russkogo Khristianskogo Dvizheniia 168 (1993), pp. 138–139. History knows cases of mass suicides of Russian displaced persons who did not want to be repatriated to the USSR. To this day, for instance, the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia (ROCOR) commemorates the tragic date of June 1, 1945, when over 25,000 Cossacks from a camp near the Austrian town of Lienz were handed over by the British authorities to their Soviet allies. As a sign of protest against this, around 700 Cossacks shot themselves, and around 600 others (mostly women and children) drowned themselves in the Drave river. [16] “Panikhida po zhertvam Lientsa” [“Panikhida for the Victims of Lienz”], in: Pravoslavnaia Rus’ [Orthodox Russia] 12 (1801), June 15/28, 2006. Mass suicides occurred again on August 12, 1945, in Kempten, Peggez, Dachau, and other DP camps. It is well known that ROCOR First Hierarch Metropolitan Anastassy (Gribanovskii) gave permission for funeral services to be held for those who had committed suicide in this way (something without precedent in Church history), saying: “Their actions are more similar to the heroism of Saint Pelagia of Antioch, who cast herself down from a tall tower in order to avoid being defiled, rather than to the transgression of Judas.” [17] Quoted in: A. A. Kornilov, . Dukhovenstvo peremeshchennykh lits. Biograficheskii slovar’. [DP Clergy. A Biographical Dictionary] Nizhny Novgorod, 2002. p. 8.

The forced repatriation of displaced persons undertaken by the Soviet regime and the response of the displaced persons themselves to this persecution shook the West and compelled General Dwight Eisenhower, the commander of the American forces in Europe, to put a temporary stop to the forced extradition of displaced persons who did not wish to be repatriated to the USSR. Later, Eisenhower himself explained the reasons for this decision as follows: “The truly unfortunate were those who, for one reason or another, no longer had homes or were ‘persecutees’ who dared not return home for fear of further persecution. The terror felt by this last group was impressed on us by a number of suicides among individuals who preferred to die rather than return to their native lands. In some instances these may have been traitors who rightly feared the punishment they knew to be in store for them. But in many other cases they belonged to the oppressed classes and saw death as a far less terrifying thing than renewed persecution.” [18] Dwight D. Eisenhower, Crusade In Europe. London: William Heinemann, 1948. p. 479. On December 22, 1945, the so-called “Truman directive” was adopted giving permission for more than 40,000 refugees from World War II to enter the USA. However, the majority of the DPs did not have the funds to pay for their trip to the Americas; thus, in the early months of 1946, only 2,500 DPs made use of this permission.

In point of fact, the only people who came to the aid of the disenfranchised inhabitants of the DP camps were the Orthodox clergy, who shared in the difficulties of their existence as refugees. In the memoirs of Russian refugees who passed through these camps, we read: “…all these people were frightened, often mentally ill, and required assistance from an experienced priest. After all, it was understood at the time that this was an unnatural life and it could not go on for long, that is is some kind of intermission between two acts. The curtain had already come down on the first, malignant act, but it had not yet risen over the second one. Who then was able to help these suffering people? Only a priest, a good soul, through his prayers. Without this assistance, a person would suffer and perish.” [19] Nun Ioanna Pomazanskaia, “Pastyr’ v gody voiny” [“Wartime Pastor”], in: Pravoslavnaia Rus’ 22 (2002). According to the ROCOR, 350 Orthodox priests were serving in the Western zones of occupation (that is, in camps controlled by US, British, and French forces), yet if one considers the spiritual needs of the millions of displaced persons, there was a catastrophic lack of clergy in the DP camps.

All the priests who accompanied Bishop John (Garklāvs) in his wanderings throughout Europe were dispersed across German DP camps with refugees from the USSR and the Baltic. Under the guidance of priests, parishes were founded in the camps and improvised houses of worship were outfitted. Through the efforts of the Latvian priests, parishes were founded in the following DP camps: Hersbruck, Kempten, Memmingen, Esslingen, Weiden, Landshut, Dinkelsbühl, Würzburg, Fulda, Kleinkötz, Regensburg, Ansbach, Erlangen, Fürth, Falk, Lübeck, Colorado, Hannover, Bad Horn, Amberg, Eisenstadt, Bad Mergentheim, Dillingen, Augsburg, Fellback, Bayreuth, and others.[20]Archive of the Orthodox Church in America, Collection of Archbishop John (Garklāvs), File: “Latvijas Pareizticīgas Baznīcas Sinodes emigrācijā 1947.g. 5. un 6. februāra sēdes protokols”. In total, the Latvian clergy established around 30 new parishes in the DP camps between 1945–49. With their experience working in the Pskov Orthodox Mission or the Internal Orthodox Mission in Latvia, the Latvian priests continued to serve as missionaries in the diaspora. Bishop John regularly visited all the new Orthodox parishes in the DP camps and brought the Tikhvin Icon of the Mother of God with him on each occasion. As Archpriest Sergii (Garklāvs) recalled: “…the presence of Our Lady of Tikhvin amongst these destitute people was definitely a source of spiritual and moral strength. It is not for nothing that she began to be venerated as the ‘protectress’ of Orthodox refugees”. The refugees made every effort — physical and spiritual — to have their own churches and the ability to pray. The temporary churches and chapels in the DP camps were “constructed exceedingly simply: out of boards or sheet metal. Inside were a few icons, a simple iconostasis, a candlestand, lamps made out of tin cans— it is difficult to imagine anything simpler. Yet it was inside these structures that the fire of people’s hearts and souls was burning.”[21]Kolesnikova and Garklāvs, op. cit., pp. 67, 68. In the words of Archpriest Nikolajs Vieglais, there was a room set aside as a church, decorated by the DPs themselves rather than by the camp administration. However, “in Regensburg, we served in a Lutheran church, and in another place it was in a Catholic chapel… We served regularly in the camps, once a month or more frequently. Sometimes with the Tikhvin Icon, sometimes without.” [22] Three Orthodox Christian Priests From Latvia. Interviews with Archpriest Nikolajs Vieglais. Petaluma, California. 2006. p. 58. It should be noted that the majority of DPs had no money to pay for the services of the clergy; therefore, the clergy in the DP camps usually served without compensation, thus not differing at all from their destitute flock in material terms.

There was almost no Orthodox literature in the DP camps. Despite extremely difficult material conditions, the Latvian clergy tried to solve this problem, too. In 1946, Archpriest V. Šķiliņš, the dean for the camps in the British zone, put together and published a booklet titled “Lūgšanas un Baznīcas mācības” (“Prayers and the Teaching of the Church”) and an Orthodox calendar. In 1947, a collection of Church Slavonic “Prayers and Hymns” put together by Archpriest Nikolajs Vieglais and Bishop John (Garklāvs) was published in Hersbruck. [23]In 1953, Metropolitan Augustīns (Pētersons) published the booklet “Sagatavošanās Svētā Dievmielasta baudīšanai” (“Prayers of Preparation for Holy Communion”), and in 1954 a “Dieva … Continue reading

Fr. Ioann Legkii (later ROCOR Bishop John) and his family in Latvia. Photo: I. Legkii, Letaiushchii arkhierei [A Flying Bishop] (Moscow 2014)

One particular feature of ministry in DP camps was that the parishioners were constantly changing. Some were repatriated to the USSR, while others moved to other European countries or the Americas due to the “looming danger from the East”[29]This phrasing is from John (Garklāvs). – Cf.: Archive of the Orthodox Church in America, Collection of Archbishop John (Garklāvs), Letter of Bishop John (Garklāvs) to A. E. Bezsmertnyi, … Continue reading Priests would leave Germany along with their flock. On September 15, 1946, Fr. Ioann Briedis, who served the DP camp in Esslingen, died in a car crash. As a result, by early 1947, there were only 12 priests left in Germany with Bishop John, three of whom could not carry out their priestly duties due to their age and poor health. [30]Archive of the Orthodox Church in America, Collection of Archbishop John (Garklāvs), File: “Latvijas Pareizticīgas Baznīcas Sinodes emigrācijā 1947.g. 5. un 6. februāra sēdes protokols”. … Continue reading

After emigrating, Metropolitan Augustīns (Pētersons) contracted acute tuberculosis, for which reason he was continuously in sanatoria for most of the post-war years (initially in Oldenburg, later in Heilbronn, and from October 23, 1950 onwards in the sanatorium in Gauting). In early 1946, Priest Georgii Freimanis served as secretary to the Metropolitan; after that, chance patients volunteered to help the aging Metropolitan (in addition to tuberculosis, he was diagnosed with asthma, sclerosis, and chronic bronchitis in the sanatorium in Gauting; in 1950, his vision became so poor that he could not read typewritten texts or reply to letters, even with glasses). [31] Heinrihs Strods, Metropolīts Augustīns Pētersons. Dzīve un darbs (Rīga, 2005), 188–190. As a result, Metropolitan Augustīns could not participate in church life and was kept up to date about it by chance informants. It is obvious that his frequently completely unpremeditated and illogical actions can be explained in terms of his illness and lack of reliable information.

Immediately after emigrating, Metropolitan Augustīns broke off all contact with Bishop John (Garklāvs), deeming his consecration to be illegitimate because it had been performed by hierarchs of the Moscow Patriarchate. What is more, since Bishop John had been appointed in 1943 to replace the suspended Metropolitan Augustīns, he had the same title as Augustīns: “of Riga”. Instead of discussing controversial matters with Bishop John and the Latvian clergy, Augustīns preferred to make accusations about Bishop John in the Latvian émigré press, which caused Orthodox Latvians to begin calling him the “newspaper metropolitan”. [32]Archive of the Orthodox Church in America, Collection of Archbishop John (Garklāvs), File: “Emigrācijā esošās Latvijas Pareizticīgās Baznīcas garīdzniecības apspriedes 16. septembrī … Continue reading Despite this, in autumn 1946, Bishop John sent Archpriest Leonid Ladinskii to negotiate with Metropolitan Augustīns with the aim of “attaining peace and concord in the Church”. In his conversation with Ladinskii, the Metropolitan declared that, “under the current situation in the diaspora, when both bishops had lost touch with their roots and consequently could no longer appeal to some higher instance of ecclesiastical authority to clear up matters”, he proposed “drawing a line under everything from earlier and starting a new life, with church life being organized along the following lines: a) the ruling bishop, of Riga, would be Metropolitan Augustīns; b) Bishop John ought to receive a new title from the ruling bishop, such as Bishop of Jersik, Jerglava, etc.; c) not to address the matter of jurisdiction and not to commemorate any one of the patriarchs as Kyr-hierarch until the overall situation had been cleared up; d) to recognize Metropolitan Seraphim of Germany as Exarch of Western Europe in accordance with their residing in German territory; e) the ruling bishop ought, at his discretion, to convene a temporary church administration or a Synod with six members, taking into account the second bishop’s suggestions, though Bishop John would only be a member of the Synod and would only preside in the absence of the ruling bishop. This proposal by Metropolitan Augustīns is categorical, and in the event of any departure from it he deems further negotiations to be pointless”. A gathering of Latvian clergy discussed Metropolitan Augustīns’ proposal and resolved that the first four points were to be “rejected as canonically unfounded”; moreover, it was resolved that Metropolitan Augustīns was physically incapable of serving as administrator of the Church of Latvia due to his poor health.[33]Ibid., File: “Minutes of the Consultation of the Orthodox Latvian Clergy Abroad in Hersbruck on October 21, 1946”.

Almost concurrently with the negotiations with Archpriest Leonid Ladinskii, Metropolitan Augustīns reached out to the ROCOR Synod of Bishops (then based in Munich) asking to lift the ban imposed on him on June 15, 1942, by Metropolitan Sergii (Voskresenskii) of Vilnius and Lithuania, Exarch of the Baltic: “Since 1922, I have been ill with chronic tuberculosis, which [until now] had not bothered me particularly. Yet on July 29 of this year, I came down with a heart disease and both of these illnesses have taken on a serious form… It is possible that I may soon embark on the long journey to eternity…”. The Synod of Bishops asked Bishop John (Garklāvs) for explanations; he called for them to be “guided” in this matter by “feelings of Christian love and all-embracing forgiveness” and asked that the ban on Metropolitan Augustīns be lifted. “Showing… brotherly understanding for the ailing Metropolitan Augustīns’s difficult emotional state” and “having sufficient grounds to add to our own voices the opinion of Bishop John of Riga… who considers it fundamentally possible and desirable to lift the aforementioned ban”, the Synod of Bishops released Metropolitan Augustīns (Pētersons) from his suspension from the sacred ministry. It is interesting to note that Metropolitan Augustīns stated that he had not authorized Professor P. Starz to negotiate with the Synod of Bishops about having the ban on him lifted, since he considered the ban to be canonically illegitimate. It is likely that the sick Metropolitan simply forgot about his letter of August 18, 1946 to Professor P. Starz, in which he asked him to explain to Metropolitan Anastassy, the chair of the Synod of Bishops, that “I have one foot in the grave, so I ask most insistently” for the ban to be lifted and to be restored “alive or dead” to sacred ministry. [34]“Dokumenty po delu mitropolita Rizhskogo i vseia Latvii Avgustina (Petersonsa) «Latviiskoi papki» Arkhiva Arkhiereiskogo Sinoda Russkoi Pravoslavnoi Tserkvi Zagranitsei” [“Documents on the … Continue reading

On October 20, 1946, an agreement was signed between Metropolitan Augustīns (Pētersons) and Bishop John (Garklāvs) on organizing the work of the Latvian Orthodox Church (LOC) in the diaspora. The agreement stated that all Orthodox clergymen and laypeople who up until then had been working with either Metropolitan Augustīns and Bishop John were to be joined together into one structure, the LOC in the diaspora, which was an autonomous ecclesiastical unit. The leader of the LOC in the diaspora was considered to be Metropolitan Augustīns, and in the event of his absence, the church was to be administered by Bishop John, who kept is former title, “of Riga”. [35]“Vienošanās protokols starp Latvijas Pareizticīgas Baznīcas metropolītu Augustīnu un Rīgas bīskapu Jāni (Garklāvu) Vācijā par Latvijas Pareizticīgās Baznīcas darbības organizēšanu … Continue reading Signing this agreement was a gesture of goodwill on the part of Bishop John, who had the backing of all the Latvian clergy in Germany and oversaw actual functioning Orthodox parishes—unlike Metropolitan Augustīns, who in signing this agreement did not represent anyone apart from himself. Moreover, even after he had been formally recognized as the leader of the LOC, Metropolitan Augustīns remained in the sanatorium and did not attend a single session of the Synod, with the result that it was Bishop John who actually administered the Church.

The agreement of October 20, 1946 did not normalize relations between Bishop John and Metropolitan Augustīns, who continued to make indiscriminate complaints against the former. For instance, in 1947, the Metropolitan accused him of grabbing all the monetary resources of the LOC and valuables from the church treasury upon leaving Latvia. After considering the issue, the LOC diaspora Synod adopted a resolution saying that “these unfounded accusations are directed against the entire Orthodox Church” and appealed to Augustīns to indicate the source of these rumors in order to conduct an investigation of the case; however, the Metropolitan did not deem it necessary to reply to this appeal by the Synod. [36]Archive of the Orthodox Church in America, Collection of Archbishop John (Garklāvs), File: “Latvijas Pareizticīgas Baznīcas Sinodes (emigrācijā) 1947.gada 25.novembra ārkārtējās sēdes … Continue reading Essentially, Metropolitan Augustīns, being cut off from church life, not only did not assist in getting the work of the LOC going in the emigration, but rather introduced confusion into the already complex life in the DP camps through his poorly thought-out decisions.

Conference of the primates of the Baltic churches under the Ecumenical Throne. Left to rgiht M. Avgustin, Bishop Nicholas, M.Alexander, M. Herman. Riga. Christ Nativity cathedral. 1938. Photo: A.Gavrlii, Pod pokrovom Tikhvinskoi ikony, Tikhvin, 2009.

In spring 1947, Metropolitan Augustīns broke the agreement he had signed with Bishop John. Without obtaining permission from the LOC Synod, he reached out to Metropolitan Germanos (Strenopoulos), Exarch of the Patriarch of Constantinople in Western Europe, and requested that he receive the LOC in the diaspora into the Jurisdiction of the Patriarch of Constantinople. Metropolitan Germanos agreed to this in June 1947, and on December 14, 1948, he informed the LOC diaspora Synod that the Synod of the Patriarchate of Constantinople had received the Orthodox Latvians in Western Europe into its own jurisdiction. Subsequently, Bishop John would repeatedly stress that neither he nor the clergy from Latvia who had come to Germany along with him had approached any representatives of the Patriarchate of Constantinople with such a request, and they therefore did not consider themselves to be under the jurisdiction of said Patriarchate. [37]Cf., e.g., a letter from Bishop John (Garklāvs) on February 18, 1949, in which he stressed that he had “never written to either the Patriarch of Constantinople or to Patriarchal Exarch Germanos to … Continue reading It is interesting to note that the Synod of the LOC in the disapora took only formal notice of this jurisdictional issue, which, it would seem, was of cardinal importance to any Church. The fact of the matter is that by this point, none of the members of the Synod were worried about the issue of the jurisdictional allegiance of the LOC in the diaspora. As early as October 1, 1947, Bishop John (Garklāvs) had reached out to Metropolitan Theophilus (Pashkovskii) of All America and Canada asking to be “incorporated, along with the clergy accompanying me, into the body of the clergy of Your Church”. In his petition, Bishop John especially emphasized that, “in serving the particular spiritual needs of the Baltic people living in the DP camps, I neither entered into communion with the Karlovtsy [Synod] nor aligned myself with any other groups in the Church, instead making use of the right of temporary autonomous administration”. A Council of Bishops of the Orthodox Church in America meeting in San Francisco on November 12–13, 1947, adopted a resolution to grant this petition by the Latvian clergy. As a result, in 1948, Bishop John and the majority of the priests from Latvia were already waiting “with packed bags” to obtain formal permission from the American authorities to immigrate to the USA; thus, by then, none of them was especially worried about the issue of the jurisdiction of the LOC in the diaspora.

On June 24, 1948, the Congress of the USA passed the Displaced Persons Act, in accordance with which the United States accepted 205,000 displaced persons from the zones of occupation in Germany, Austria, and Italy, in addition to those allowed by the quota system. The United States was interested first and foremost in obtaining cheap labor. As a result, the right to resettle there was granted primarily to persons who had been engaged in agriculture, construction, or domestic work before the war. Persons with other professions were counted under the quota system. As a result, it took almost two years to resolve the issue of resettling the groups of Latvian priests headed by Bishop John (Garklāvs) to the USA. The most active assistance was provided by the Tolstoy Foundation, which had opened a European office in Munich on September 22, 1947 (with Tatiana Alexeevna Schaufuss as its director), and the Church World Service, which paid for their passage across the Atlantic ($150 per person, which they had to pay back to this organization within a year after their trip). The issue of how to pay for passage to the USA was of the utmost importance for the majority of the immigrants, since, due to a lack of financial means, they were not only unable to pay for this trip, but did not even have enough to travel to the nearest city. In the words of Bishop John (Garklāvs), in summer 1948, “due to the currency reform that deprived us of our savings for our travel expenses”, none of the Latvian priests who had submitted a petition to immigrate to the USA was able to travel to Munich to find out how his case was being decided; thus, “we are all completely in the dark concerning our status and our ability to travel”. [38] Archive of the Orthodox Church in America, Collection of Archbishop John (Garklāvs), Correspondence of Bishop John (Garklāvs) with Metropolitan Theophilus (Pashkovskii).

On July 21, 1949, Bishop John (Garklāvs) arrived in America, where he was made Bishop of Detroit and Cleveland in October 1949 (from February 1957, he was Archbishop of Chicago and Minneapolis). In summer/autumn 1949, eight Latvian priests emigrated from the DP camps in Germany, including all the clerical members of the LOC diaspora Synod (Archpriests N. Vieglais, N. Perekhval’skii, L. Ladinskii, I. Liepiņš, and P. Kurzemnieks), four subdeacons, two church choir conductors, one reader, their family members, and several Orthodox Latvian laymen (for a total of 67 persons). Thanks to Bishop John’s assistance, in subsequent years Orthodox Latvians from German DP camps were generally also resettled in the USA.

Archpriest Nicholas Perekhval’skii performs matrimony of Bishop John’s stepson Sergei in the cathedral of Protection of the Mother of God in NY. 1950. Photo: A.Gavrlii, Pod pokrovom Tikhvinskoi ikony (Tikhvin, 2009).

The LOC diaspora Synod ceased its activities after Bishop John (Garklāvs) and the majority of the Latvian priests left Germany, and with this the Latvian Orthodox Church in the diaspora effectively ceased to exist. Only one of the Orthodox priests who had emigrated from Latvia was left in Germany: Archpriest Alexis Puzanov, who, after transferring to the ROCOR, served the parish in Regensburg. Yet each year there were fewer and fewer Latvian Orthodox laypeople in Germany.

On January 20, 1955, Metropolitan Augustīns (Pētersons), the last remaining Latvian cleric in Germany, reached out to Archbishop Alexander (Lovchii, 1891–1973) of Berlin and Germany (ROCOR), asking him to assume spiritual care of the LOC flock in the diaspora, thereby formally dissolving the church body of the LOC. He restated the same request in a letter of June 21, 1955 to the Evangelische Verlagsanstalt: “In response to your letter of June 15, 1955, I would like to inform you that I am the sole [remaining] clergyman of the Latvian Orthodox Church. I am 82 years of age and I am currently receiving treatment for tuberculosis in a sanatorium in Gauting. The members of the Orthodox Church of Latvia are spread across Germany in camps, sanatoria, old people’s homes, and private apartments. I would kindly like to ask Archbishop Alexander of Berlin to issue a decree to the effect that the clergy under him should take up the spiritual care of these members of the Latvian Orthodox Church”. [39]Archive of the ROCOR Synod of Bishops, Tserkovnye Vedomosti Pravoslavnoi Tserkvi v Germanii. Offitsial’nyi organ Pravoslavnoi Germanskoi Eparkhii [Church Bulletin of the Orthodox Church in … Continue reading

References

| ↵1 | Benigsen, Georgii, Archpriest. “Khristos-pobeditel’” [“Christ Victor”], in: Vestnik Russkogo Khristianskogo Dvizheniia 168 (1993), pp. 138–139. |

|---|---|

| ↵2 | Z. Balevics, Pareizticīgo baznīca Latvijā (Rīga, 1987) 135, 139. |

| ↵3 | Quoted in: Mikhail Shkarovskii, Tserkov’ zovet k zashite Rodiny. Religioznaia zhizn’ Leningrada i Severo-Zapada v gody Velikoi Otechestvennoi voiny. Saint Petersburg, 2005. p. 208. |

| ↵4 | Metropolitan Augustīns of Riga and All Latvia (secular name: Augustīns Pētersons, 17.02.1873 – 07.10.1955) was born into a peasant family. After graduating from Riga Theological Seminary, he served as a church reader and a teacher in church schools in Suntaži, Kaplavi, and Liepāja. In 1905, he married Olga Sholomok, and in the same year he was ordained Deacon by Bishop Agafangel (Preobrazhenskii) of Riga and Mitava, and subsequently as priest. He served as a reader in Suntaži and Smiltene. During World War I, he was chaplain to the 225th Skopin Regiment, from 1915 chaplain at the military hospital for infectious diseases, and from 1916 chaplain of the Latvian Riflemen’s Reserve Regiment. He returned to Latvia in August 1921. From 1921 onwards, he was a priest at Alexander Nevsky Cathedral in Daugavpils, from 1922 rector of Saints Boris and Gleb Cathedral in Daugavpils, and from 1926 a priest in the Daugavpils garrison. On May 26, 1922, he was elevated to the rank of archpriest. In 1934, he became a widower (with three sons). On March 10, 1936, he was elected head of the Latvian Orthodox Church (Patriarchate of Constantinople).

On March 29, 1936, Augustīns was consecrated Metropolitan of Riga and All Latvia. His consecration was performed by hierarchs of the Patriarchate of Constantinople: Metropolitan Germanos of Thyateira, Metropolitan Thomas of Principe, Metropolitan Konstantinos of Irinopolis, Metropolitan Alexander of Tallinn and All Estonia, and Archbishop Nikolai of Petseris. On March 29, 1941, Metropolitan Augustīns repented of the sin of schism and was received into canonical communion with the Moscow Patriarchate, after which he was sent on leave at his own request. At the beginning of the Nazi occupation of Latvia, Metropolitan Augustīns had opposed Metropolitan Sergii (Voskresenskii) of Latvia and Estonia, which caused Metropolitan Sergii to suspend Augustīns (Pētersons) from the sacred ministry. Without support from the clergy, laity, or Nazi occupying authorities, Metropolitan Augustīns was forced to submit to this decision. In August 1944, he emigrated to Germany. He passed away in a sanatorium for tuberculosis patients near Munich on October 7, 1955. Cf.: “Dokumenty po delu mitropolita Rizhskogo i vseia Latvii Avgustina (Petersonsa) «Latviiskoi papki» Arkhiva Arkhiereiskogo Sinoda Russkoi Pravoslavnoi Tserkvi Zagranitsei” [“Documents on the Case of Metropolitan Augustīns (Pētersons) of Riga and All Latvia from the ‘Latvian File’ of the Archive of the Synod of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia”], in: Pravoslavie v Latvii. Istoricheskie ocherki [Orthodoxy in Latvia. Historical Surveys], No. 5. Collection of articles edited by A. V. Gavrilin (Riga, 2006), 97–144. |

| ↵5 | “Metropolīts Augustīns Felbahā”, in: Latviešu Vēstnesis. 1946. g. 27 jūl. At this time, Metropolitan Augustīns Pētersons’ son, captain Georgis Pētersons of the SS Latvian legion, was in Germany for medical treatment. Metropolitan Augustīns thus had personal reasons not to protest against being deported to Germany. Cf.: Heinrihs Strods, Metropolīts Augustīns Pētersons. Dzīve un darbs. Rīga, 2005. pp. 175-176. |

| ↵6 | Three Orthodox Christian Priests From Latvia. Interviews with Archpriest Nikolajs Vieglais. Petaluma, California, 2006. pp. 50-51. |

| ↵7 | John (Jānis Garklāvs, 26.08.1898–11.04.1982) was born into a peasant family. From 1907–1912, he was a pupil at the church school in Limbaži. In 1915, he joined the Riflemen’s regiment as a volunteer. He was involved in World War I and the Russian Civil War. In 1921, he returned to Latvia. From 1924–1933, he was a reader at Alexander Nevsky Church in Limbaži. From 1933–1936, he studied at Riga Theological Seminary. On September 27, 1936, he was ordained as a priest at the Holy Nativity Church in Kolkasrags by Bishop Iakov (Karp) of Jelgava, and he also served at Saint Arsenius Church in Kjul’ciems and Saints Constantine and Helen Church in Dundaga. From 1942 until January 1943, he was a priest at the Holy Spirit Monastery in Vilnius. On November 28, 1943, he was tonsured as a monk with the name John. On February 28, 1943, he was consecrated Bishop of Riga at Holy Nativity Cathedral in Riga. The ordination was performed by Metropolitan Sergii (Voskresenskii), Archbishop Iakov (Karp) of Jelgava, and Bishop Daniil (Iuzv’iuk) of Kaunas. From 1944–1949, he resided in Germany, where he provided pastoral care for DP camps. In July 1949, he emigrated to the USA, where he became Bishop of Detroit and Cleveland in the Orthodox Church in America, and from February 1957, he was Archbishop of Chicago and Minneapolis. He retired in November 1978 and is buried in Saint Tikhon’s Monastery (South Canaan, Pennsylvania). |

| ↵8 | L. A. Kolesnikova, Archpriest Alexander Garklāvs, Tikhvinskaia ikona Bozhiei materi. Vozvrashchenie. [The Tikhvin Icon of the Mother of God. The Return.] Saint Petersburg, 2004. pp. 62–63. |

| ↵9 | Archim Kyrill Nachis, “Narod zhazhdal molit’sia, zhazhdal pokaianiia…” [“The People Were Thirsting for Prayer, Thirsting for Repentance…”], in: Sankt-Peterburgskie eparkhial’nye vedomosti [Saint Petersburg Diocesan Bulletin] 26–27. Saint Petersburg, 2002. p. 202. |

| ↵10 | Golikov, Andrei, Priest, and Fomin, S. Krov’iu ubelennye. Mucheniki i ispovedniki Severo-Zapada Rossii i Pribaltiki [Whitened by Blood. Martyrs and Confessors of North-western Russia and the Baltic]. Moscow, 1999. p. 113–116. |

| ↵11 | Daniil (Nikolai Porfirievich Iuzv’iuk, 02.10.1880–27.08.1965) graduated from Vilnius Theological Academy, and taught at Vilnius Theological Seminary from 1925–1939. From 1939 onwards, he was secretary to Metropolitan Elevferii (Bogoiavlenskii) of Lithuania and Vilnius. In April 1942, he was ordained Bishop of Kaunas. From April 29, 1944 onwards he was temporary administrator of the Diocese of Lithuania and, as Archbishop, of the Exarchate of Latvia and Estonia. He was evacuated to Czechoslovakia. From December 30, 1945 onwards he was Archbishop of Pinsk and Brest, and was imprisoned from 1950–1954. He retired in 1956 and spent the time until his death in various monasteries. |

| ↵12 | Three Orthodox Christian Priests From Latvia. Interviews with Archpriest Nikolajs Vieglais. Petaluma, California, 2006. p. 56. |

| ↵13 | P. M. Vunduka, “Deistviia MKKK v zashchitu bezhentsev i peremeshchennykh lits” [“Actions of the International Red Cross to Protect Refugees and Displacd Persons”], in: Mezhdunarodnoe publichnoe i chastnoe pravo [International Public and Private Law] 4 (2002), p. 31. |

| ↵14 | Nitoburg, E. L. “U istokov russkoi diaspory v SShA: Tret’ia volna” [“On the Origins of the Russian Diaspora in the USA: The Third Wave”], in: SShA – Kanada: Ekonomika. Politika. Kul’tura [The USA and Canada: Economy, Politics, Culture], 1 (1999). p. 84. |

| ↵15 | [ref]Archpriest Georgii Benigsen, “Khristos-pobeditel’” [“Christ Victor”], in: Vestnik Russkogo Khristianskogo Dvizheniia 168 (1993), pp. 138–139. |

| ↵16 | “Panikhida po zhertvam Lientsa” [“Panikhida for the Victims of Lienz”], in: Pravoslavnaia Rus’ [Orthodox Russia] 12 (1801), June 15/28, 2006. |

| ↵17 | Quoted in: A. A. Kornilov, . Dukhovenstvo peremeshchennykh lits. Biograficheskii slovar’. [DP Clergy. A Biographical Dictionary] Nizhny Novgorod, 2002. p. 8. |

| ↵18 | Dwight D. Eisenhower, Crusade In Europe. London: William Heinemann, 1948. p. 479. |

| ↵19 | Nun Ioanna Pomazanskaia, “Pastyr’ v gody voiny” [“Wartime Pastor”], in: Pravoslavnaia Rus’ 22 (2002). |

| ↵20 | Archive of the Orthodox Church in America, Collection of Archbishop John (Garklāvs), File: “Latvijas Pareizticīgas Baznīcas Sinodes emigrācijā 1947.g. 5. un 6. februāra sēdes protokols”. |

| ↵21 | Kolesnikova and Garklāvs, op. cit., pp. 67, 68. |

| ↵22 | Three Orthodox Christian Priests From Latvia. Interviews with Archpriest Nikolajs Vieglais. Petaluma, California. 2006. p. 58. |

| ↵23 | In 1953, Metropolitan Augustīns (Pētersons) published the booklet “Sagatavošanās Svētā Dievmielasta baudīšanai” (“Prayers of Preparation for Holy Communion”), and in 1954 a “Dieva lūgšanas grāmata” (“Prayer Book”). However, these books never became widespread, since by that time the DP camps in Germany had been dismantled. |

| ↵24 | Archive of the Orthodox Church in America, Collection of Archbishop John (Garklāvs), File: “Latvijas Pareizticīgas Baznīcas Sinodes emigrācijā 1947.g. 5. un 6. februāra sēdes protokols”. |

| ↵25 | Archpriest Georgii Beingsen (1915–1993) served in the Holy Resurrection Cathedral in Berlin and moved to the USA in late 1950, where he transferred to the jurisdiction of the Orthodox Church in America. |

| ↵26 | Archpriest Ioann Legkii (1907–1993) served in Neu Freimann Camp, and from 1946 as a rector of churches in Lübeck and Schleswig. He moved to the United States in August 1949. He was a priest at Holy Ascension Cathedral in the Bronx from 1949–1959 and rector of Holy Archangel Michael Cathedral in Paterson from 1959–1987. In 1987, he retired, and in 1990 he received the monastic tonsure and was consecrated bishop of Buenos Aires, Argentina and Paraguay. Cf.: Gavrilin, A. “‘Neizvestnye’ latviiskie sviashchennosluzhiteli: otets Ioann Legkii” [“‘Unknown’ Latvian Clergymen: Father Ioann Legkii”], in: Pravoslavie v Latvii. Istoricheskie ocherki [Orthodoxy in Latvia. Historical Surveys], No. 5. Collection of articles edited by A. V. Gavrilin. Riga, 2006. p. 97–144. |

| ↵27 | Priest Ioann Baumanis (1908–1983) served in Würzburg. With the blessing of Metropolitan Anastassy (Gribanovsky), he traveled to Brazil disguised as an agricultural worker, and later to Venezuela. He founded five Orthodox parishes in Venezuela and was made protopresbyter in 1975. Cf.: Kornilov, op. cit., pp. 61–62. |

| ↵28 | Archive of the Orthodox Church in America, Collection of Archbishop John (Garklāvs), “Letter of Archpriest Ioann Baumanis to Bishop John (Garklāvs), December 6, 1948”. |

| ↵29 | This phrasing is from John (Garklāvs). – Cf.: Archive of the Orthodox Church in America, Collection of Archbishop John (Garklāvs), Letter of Bishop John (Garklāvs) to A. E. Bezsmertnyi, Secretary to Metropolitan Theophilus (Pashkovskii) of All America and Canada, June 27, 1948. |

| ↵30 | Archive of the Orthodox Church in America, Collection of Archbishop John (Garklāvs), File: “Latvijas Pareizticīgas Baznīcas Sinodes emigrācijā 1947.g. 5. un 6. februāra sēdes protokols”. In 1948, Peteris Kurzemnieks and Antonii Gramatiņš were ordained as priests, but this did not solve the problem of the clergy shortage, since priests were leaving Germany each year. As a result, the number of LOC priests in the diaspora varied from 8–9. |

| ↵31 | Heinrihs Strods, Metropolīts Augustīns Pētersons. Dzīve un darbs (Rīga, 2005), 188–190. |

| ↵32 | Archive of the Orthodox Church in America, Collection of Archbishop John (Garklāvs), File: “Emigrācijā esošās Latvijas Pareizticīgās Baznīcas garīdzniecības apspriedes 16. septembrī 1946.g. Hersbrukā Protokols”. |

| ↵33 | Ibid., File: “Minutes of the Consultation of the Orthodox Latvian Clergy Abroad in Hersbruck on October 21, 1946”. |

| ↵34 | “Dokumenty po delu mitropolita Rizhskogo i vseia Latvii Avgustina (Petersonsa) «Latviiskoi papki» Arkhiva Arkhiereiskogo Sinoda Russkoi Pravoslavnoi Tserkvi Zagranitsei” [“Documents on the Case of Metropolitan Augustīns (Pētersons) of Riga and All Latvia from the ‘Latvian File’ of the Archive of the Synod of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia”], in: Pravoslavie v Latvii. Istoricheskie ocherki [Orthodoxy in Latvia. Historical Surveys], No. 5. Collection of articles edited by A. V. Gavrilin. Riga, 2006. pp. 97–144. |

| ↵35 | “Vienošanās protokols starp Latvijas Pareizticīgas Baznīcas metropolītu Augustīnu un Rīgas bīskapu Jāni (Garklāvu) Vācijā par Latvijas Pareizticīgās Baznīcas darbības organizēšanu trimdā 1946. gada 20. oktobrī”, in: Strods, Heinrihs. Metropolīts Augustīns Pētersons. Dzīve un darbs. Rīga, 2005. p. 266. |

| ↵36 | Archive of the Orthodox Church in America, Collection of Archbishop John (Garklāvs), File: “Latvijas Pareizticīgas Baznīcas Sinodes (emigrācijā) 1947.gada 25.novembra ārkārtējās sēdes protokols №3”. |

| ↵37 | Cf., e.g., a letter from Bishop John (Garklāvs) on February 18, 1949, in which he stressed that he had “never written to either the Patriarch of Constantinople or to Patriarchal Exarch Germanos to petition to be received into their jurisdiction. As far as I am aware, Prof. Starz wrote to Germanos with this request at the behest of Metropolitan Augustīns. But this does not concern me – to be precise, it does not oblige me to be in the jurisdiction of the Patriarchate of Constantinople. We just wrote to the editors of the journal and asked them to rescind or correct this mistake. Our group, on the basis of my petition, was received into the Orthodox Russian Church of North American at a Council of Bishops that convened on November 12–13, 1947, in the city of San Francisco, and it is to this Church that we remain loyal. Cf.: Archive of the Orthodox Church in America, Collection of Archbishop John (Garklāvs). |

| ↵38 | Archive of the Orthodox Church in America, Collection of Archbishop John (Garklāvs), Correspondence of Bishop John (Garklāvs) with Metropolitan Theophilus (Pashkovskii). |

| ↵39 | Archive of the ROCOR Synod of Bishops, Tserkovnye Vedomosti Pravoslavnoi Tserkvi v Germanii. Offitsial’nyi organ Pravoslavnoi Germanskoi Eparkhii [Church Bulletin of the Orthodox Church in Germany. Official Organ of the Orthodox Diocese of Germany] 7/8/9. July/August/September 1955. Munich, p. 9. |

A very interesting article. It unfortunately doesn’t mention the large number of Latvian DPs (some of whom were Orthodox) who came to Britain. They included two remarkable priests: Anthony Gramatins and Alexander Cherney. I remember them both well. Archpriest Anthony served various Latvian communities as well as helping the ROCOR diocese here. Father Alexander wrote several works about his earlier life as well as a short but useful history of the Orthodox Church in Latvia (in English).