Fr. Nikolaj serves in Holy Resurrection Serbian Orthodox Cathedral in Chicago. He is the author of the unique research on the relationship between ROCOR and North American Metropolia. Read an interview with Fr. Nikolaj, The OCA and the ROCOR Have a Common Root in Pre-Revolutionary Russian Church. We strongly hope that he will benefit from his research even more in the near future.

Fr. Nikolaj serves in Holy Resurrection Serbian Orthodox Cathedral in Chicago. He is the author of the unique research on the relationship between ROCOR and North American Metropolia. Read an interview with Fr. Nikolaj, The OCA and the ROCOR Have a Common Root in Pre-Revolutionary Russian Church. We strongly hope that he will benefit from his research even more in the near future.

This thesis has been approved by Holy Trinity Seminary Class according to Bachelor of Theology requirements in historical background, an expose on relations between Serbia and Russia, an outline of conditions of the Serbian Church (SOC) at the dawn of the 1920s, an analysis of the impact of the ROCOR in spheres of theology, monasticism and missionary;contributions of the SOC toward healing the Russian ecclesiastical divisions.

Acknowledgments

This thesis is dedicated to my parents, Archpriest Lazar and Protinica Mira Kostur. I would sincerely like to thank all that have offered their help to me in the completion of this work. Among those, I would like to thank those that have gone the extra mile in helping me:

His Holiness, Patriarch Pavle of Serbia who gave me his patriarchal blessing to research in the Archives of the Serbian Orthodox Church in Belgrade.

His Eminence, Metropolitan Laurus, First-Hierarch of the Russian Church Abroad, who offered me his advice in the research of this paper, as well as for giving me his archpastoral blessing to conduct research in the Archive of the Synod of Bishops in New York.

His Grace, Bishop Longin of New Gracanica, for his assistance and recommendations for the research of this work that was done in Serbia.

His Grace, Bishop Michael of Boston, who offered his advice in my research for the later period of the Russian Church’s existence in Serbia.

His Grace, Bishop Peter of Cleveland, who offered his advice in my research, giving me ideas of where to acquire information.

My academic advisor, Andrei Vadimovich Psarev, who offered countless hours of service, helping me find sources and offering his opinions and encouragement throughout the entire process of research and writing. He also acquired sources for me from Riasaphor-Nun Vassa (Larin). Without him, the completion of this project would have been impossible.

Protopresbyter-Stavrofor Mateja Matejic for his advice and support in the research of this thesis.

My father, Archpriest Lazar Kostur, who inspired me to research such topics as relations between the two churches. Throughout the entire work, he constantly encouraged me to continue on with my research to the glory of the Serbian and Russian Churches.

Archpriest Savo Jovic, Secretary of the Synod of Bishops of the Serbian Orthodox Church and Director of the Archives in the Serbian Orthodox Patriarchate. He, along with Hieromonk Irinej (Dobrijevic), offered me much guidance and help throughout my research in the Patriarchal Archives.

Priest Serafim Gan, who assisted me in the Archives of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad in New York.

Deacon Vladimir Tsurikov, Assistant Dean of Holy Trinity Seminary, for assisting me in the Archives of Holy Trinity Seminary in the Maevskii File as well as in the Seminary Library.

Riasaphor-Monk Vsevolod (Filipev) for allowing me to work with the materials from the Pravoslavnaia Rus’ Archive at Holy Trinity Monastery.

Professor Nadieszda Kizenko, the second reader of this thesis, who made valuable suggestions during the review process.

Anatoly Sumelev RFE/RL Project Archivist at the Hoover Institution Library and Archive for providing me with documents from the Stanford University Library.

To any that I have missed, I wish to also thank you and ask for your forgiveness.

Part I: Introduction

The Purpose of this Work

In contemporary Orthodox America, as well as the rest of the world, the correct understanding of Orthodox Church relations is unknown, people often forgetting the historical events that have taken place in the Orthodox Church, especially in the Twentieth Century. An area of great concern is the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad. I personally, as a Serbian Orthodox Christian studying at Holy Trinity Seminary and living at Holy Trinity Monastery in Jordanville, NY – the true spiritual center of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad – feel a great connection between my Mother-Church, the Serbian Orthodox Church, and my Surrogate Mother-Church, the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad. Because of the upbringing that I have received in both places, I felt it my duty to undertake a work so important for both Churches. I seek to prove that the relationship between the Churches is much closer than that which is believed, and that the relationship that the Serbian Church has held with both parts of the Russian Church, that is, with the Russian Church Abroad as well as with the Russian Church of the Moscow Patriarchate, spiritually connects the Russian Churches through their common Sister-Church, the Serbian Orthodox Church.

This thesis seeks to examine the relationship of the Serbian Orthodox Church to the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad, mainly between the arrival of the Russians up until the beginning of World War II, which is a large portion of the Russians’ stay in Yugoslavia. Because no work like this has ever been undertaken before, the goal was to collect as much information as possible from numerous sources in order to better understand the relationship of the two churches. The main focuses are on the actions of the Serbian Patriarchs regarding the First-Hierarchs of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad and the involvement of the Serbian Orthodox Church as a mediator between the troubled Russian Churches, along with other important relevant contemporary details.

In short, the goal of this thesis is to closely analyze the relationship of the Serbian Orthodox Church to the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad between 1920 and 1941 in order to better understand the close connection of the two churches, especially between each Churches’ guiding hierarchs; with hopes of completing this goal, it is believed that many will benefit in the Serbian Church as well as in the Russian Churches, so that a better understanding will be acquired by all to the glory of God, Who abides fully in the Serbian Church as well as in all the parts of the one Russian Church.

Historiography

Hitherto, there does not exist a study on the relationship of the Serbian Orthodox Church to the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad. Thus, the sources for this work were sought out in many different places in order to come up with an accurate description of the relations.

A wealth of information was acquired for this thesis from the Archive of the Serbian Orthodox Church in Belgrade, Serbia. Other information was gathered from the Archives of Holy Trinity Seminary and Pravoslavnaia Rus’, both in Jordanville, New York, the Archive of the Synod of Bishops in New York, the Stanford University Library, and the State Archives of the Russian Federation (GARF) in Moscow.

Some important sources for the study of the subject of this thesis are the periodicals of the Synod of Bishops of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad, Tserkovnyia Vedomosti (1922-1930)[1]1 The years reviewed indicated in parenthesis and Tserkovnaia Zhizn’ (1933-1941). These periodicals contain official documents, articles, and letters by authoritative representatives of both the Serbian Orthodox Church and the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad.

Zhurnal Moskovskoi Patriarkhii and Golos Litovskoi Pravoslavnoi Eparkhii provided me with relevant information in regards to the relationship of the Serbian Orthodox Church to the Russian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate), especially in the section dedicated to the intermediation of the Serbian Orthodox Church between the Russian Churches.

The book Russkaia Tserkov’ v Iugoslavii by V.I. Kosik, which was printed at St. Tikhon’s Orthodox Theological Institute in Moscow, was of incredible use to this work in that it provided a large amount of information in regards to the point of view of the Russian hierarchs, clergy and laity in Yugoslavia as well as providing me with many historical facts.

The pamphlet The Truth About the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad written by M. Rodzianko was very useful in the writing of this thesis, it having a wealth of historical facts of a polemical nature in regards to the history of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad.

The History of the Serbian Orthodox Church by Paul Pavlovich was a necessary tool in depicting historical events of the Serbian Orthodox Church before and during the presence of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad in Yugoslavia.

The books Kanonicheskoe Polozhenie Vysshei Tserkovnoi Vlasti v SSSR i Zagranitsei by Protoierei Mikhail Pol’skii and Pravovoe Polozhenie Russkoi Tserkvi v Iugoslavii by Sergei Viktorovich Troitskii were invaluable for their providing of some historical facts regarding the canonical situation of the Russian Church.

The series of books entitled Zhizneopisanie Blazhenneishago Antoniia, Mitropolita Kievskago i Galitskago by Bishop Nikon (Rklitskii) were very valuable in providing details of Metropolitan Antonii’s acts, as well as the acts of the Higher Church Authority relevant to the arrival of the Russians in Belgrade. However, the series is written with a strong “agiographic” approach.

The manuscript The History of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad, as well as the book Monasteries and Convents of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad by Fr. George Seide both, provided important historical information relevant to the topic. While researching his works, however, I realized that there are many historical inaccuracies which can cause confusion. For example, incorrect dates were listed for certain major events in the manuscript The History of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad.

The book Srpski Jerarsi by the late Bishop Sava of Shumadija which was published in 1996 in Serbia was very helpful in providing information about the hierarchs of the Serbian Orthodox Church involved in the life of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad.

The book entitled Serbskii Patriarkh Varnava i ego vremia by V.A. Maevskii was also an important source in that it provided information about Patriarch Varnava’s life and actions from an inside point of view, Maevskii having been Patriarch Varnava’s secretary for a number of years.

The collections of acts of the First (1921) and Second Pan-Diaspora (1938) Councils were also important sources for understanding the relations of the two churches.

Pravoslavnaia Rus’, Pravoslavnaia Zhizn’, Pravoslavnyi Put’ and Orthodox Life, all publications of Holy Trinity Monastery, provided me with articles relevant to my research. Pravoslavnyi Put’ was especially helpful in the section related to the Carpathian Diocese.

Glasnik, the official news organ of the Serbian Orthodox Church, was also used. Unfortunately, do to the lack of time that was available in Belgrade, I was unable to research the entire time frame pertinent to this thesis.

Note on Transliteration and Style

All names are transliterated into the English language according to the Library of Congress System based on the language of the original source. The style of usage is according to the MLA Handbook, Fourth Edition.

Part II: Historical Information

Serbia and Russia – The Bonds of Two Churches

Serbia and Russia have been united spiritually for centuries. This is due to the Orthodox-Slavic connection of the peoples. For example, when Montenegro was independent from Serbia [2] Montenegro was never nationalistically divided from Serbia. It was a separate state due to the Turkish Yoke; the Church in Montenegro was Serbian, even though it was under self-rule., the church officials (a political theocracy with a metropolitan and a king, united in the same person) always appealed to Russia for aid. For example, Metropolitan Sava of Montenegro was in close contact with Russia, constantly seeking spiritual aid in his defense against Roman Catholicism. Metropolitan Vasilije of Montenegro died in 1766 in Russia and is buried in the cathedral of the Annunciation in St. Petersburg, after having fled to Russia in fear of the Turks [3]Sava 60-61, 431. In 1833 Metropolitan Petar II Petrovich Nyegosh, King of Montenegro, was consecrated to the episcopacy by the Russian Church [4]Puzovich 218. During the Turkish Yoke (1389-1804), the Serbian Church would get virtually all of its Church Slavonic service books from Russia, the Serbs’ books having been destroyed by the Turks. In Tsetinje, Montenegro, the see of the Metropolitan of Montenegro, such clerical items as vestments, Gospels, and other books are displayed in the museum of the monastery – all these gifts were of the Russian Empire to the Serbian Church in Montenegro. Nor was the exchange one-sided. The Russian Church also had Metropolitans of Serbian descent as well as other Serbs involved in its life. One well-known example is Pakhomii the Serbian Logofet of the Fifteenth Century. He was a professional scribe and translator who also wrote saints lives, encomia, services, and canons [5]Kuskov 116. In short, the Churches were united very closely, giving each other spiritual support for many years.

Serbia and Russia – Politically United

Serbia and Russia were also connected politically, supporting each other in every way, especially on the part of the Russians. Russia annually sent monetary subsidies to Montenegro [6]Puzovich 218. The Russian Empire also came to the military defense of Serbia. For example, when Austro-Hungary gave the Serbs an ultimatum of war after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand by Gavrilo Printsip on June 15/28, 1914 [7]June 15/28 is Vidovdan, the day of the commemoration of the Battle of Kosovo (1389) . This, although a day of worldly defeat, is considered to be one of the greatest Serbian Feasts of Spiritual … Continue reading, Czar Nicholas II responded. He wrote to the Prince-Regent Alexander of Serbia on July 1/14: “As long as there is at least a bit of hope in the aversion of bloodshed, all of our efforts must be directed to that goal. But, if contrary to our sincere desires, we are not able to make progress, Your Highness may be assured that Russia will in no way be left indifferent to the participation of Serbia.” [8]Kosik 22 .

The Serbian Orthodox Church at the Dawn of the 1920’s

To understand the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad’s (ROCA) position in Serbia, one must first understand the political and ecclesiastical situation in Yugoslavia at the end of the 1910’s and at the beginning of the 1920’s. Politically, a drastic change had taken place. First, Yugoslavia was a completely new name for the nation. Yugoslavia had been known as “The Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes”. At the end of World War I (1918), however, the Allied Powers had granted all of the territories that was to become Yugoslavia to the nation with the ability for its expansion into a Greater Serbia; however, King Peter I of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes decided to change it to Yugoslavia, literally meaning Southern Slavs. This was very uncomfortable for the Serbian Church. The Church understood that, as a result, it would lose certain religious freedoms it had enjoyed since the break away from Austro-Hungary, this being due to the political unification of different nationalities which had different beliefs [9]Pavlovich 220. The Serbian Church was also in a state of irregularity, being divided into five different self-ruled jurisdictions (Spasovich 157). These were the Serbian Church in Serbia proper, the Church of Montenegro, the Church of Karlovats, the Church of Bukovinsko-Dalmatia and the Church of Bosnia-Herzegovina [10]“Gramota”. Tserkovnyia Vedomosti. No. 8-9 1922: 2 . The two last groups were autonomous under the Patriarchate of Constantinople. [11] Pavlovich 221 .

It was only in June of 1919 that these five jurisdictions were reunited by Metropolitan Dimitrii of Serbia into one unified Serbian Orthodox Church [12] Spasovich 157 . At this time, Prince Alexander made it clear that the Serbian Church was to lose its status as the National Church and was to lower itself and be considered on the same level as other churches, such as the Roman Catholics. This was not a new decision. Already in January of 1919, the state had declared equality among the Orthodox, Roman Catholics and Moslems. From September 9-12, 1920, the Serbian Orthodox Church held a Council of Bishops. At the meeting, it was decided to bring back a Patriarchate [13] Pavlovich 220-221. On September 28/October 11, 1920, Metropolitan Dimitrii of Serbia was elected to be Patriarch of Serbia, but the enthronement could not take place immediately [14] Spasovich 157. The government of Yugoslavia desired to be a part of the election process and hence insisted on having a vote in the election of Patriarch. The government was given three candidates by the Assembly of Bishops. On November 12/25, 1920, the government of Yugoslavia also elected Metropolitan Dimitrii as Patriarch of Serbia [15] Pavlovich 221-222. For the first time in over one hundred and fifty years, a Serbian Patriarch was on the Serbian Patriarchal Throne [16] Spasovich 157 . This showed the earlier declaration of equality of religions to be weak. The Serbian Church then was going through turmoil. Because of its problematic status, the entry of another Orthodox jurisdiction was bound to cause problems.

Part III: The 1920’s

The Russians Move

On September 5/18, 1920, Metropolitan Antonii (Khrapovitskii) received a telegram while on Mount Athos from the Russian White Army General Petr Nikolaevich Vrangel’. The telegram asked for Metropolitan Antonii, the senior bishop of the Russian Church outside Soviet Russia, to come to the Crimea and administrate the Church of the White Army there. Metropolitan Antonii accepted the invitation and went to the Crimea. Within forty days, no one was able to stay there. The Bolsheviks started moving towards the Crimea and the White Army was forced to move farther away from the Bolsheviks.

It is necessary to mention the connection between the White Army and the Russian Church. The White Army had the complete support of the Russian Church on the territories of its control, this is why Metropolitan Antonii accepted the invitation of the general. [17]Khrapovitskii 80 Finally, no choice was left and evacuation was imminent. About 150,000 people were put in boats on November 6/19, 1920, and headed for Constantinople. Among these people were Russian Church Hierarchs, military, intelligentsia and people of all walks of life, united together with one common goal, that of saving their lives. These people were led by General Petr Nikolaevich Vrangel’. He began the journey with his people, leading them to safety. Unfortunately, all could not be taken along. Every boat in Sevastopol was used for this journey, and all were full. Those who were left behind could only expect the worst. Since the Russian clergy shared the life of the Russian Army in its defense of Holy Russia, it was natural for them to evacuate together with the army [18]Rklitskii, Vol. V, 5 .

In leaving for Constantinople, Metropolitan Antonii based his canonical right to go with the flock on the 39th Canon of the Sixth Ecumenical Council (691) which states that a diocese “with all its people may be moved due to the reason of barbaric attacks in order to free itself from pagan slavery.” [19]Rklitskii, Vol. V, 6 . This would prove extremely important later. The day the bishops arrived, November 6/19 1920, a meeting of the Higher Church Authority (HCA)[20]4 When communication was cut off with Moscow during the civil war, the bishops of southern Russia were forced to convene a council in Stavropol’. The council took place in 1919. “At this Council … Continue reading was held. At this meeting, several points were established. First, the HCA would exist in Constantinople with the blessing of the Patriarchate of Constantinople, to spiritually feed the Russian flock and the canonical situation of the HCA would have to be decided by the Patriarch of Constantinople. It was also determined who would be a part of the HCA (Rklitskii 6-12). For this reason, Metropolitan Antonii made sure to receive clearance from all the local Orthodox Churches that had canonical territory over an area where any Russian parish was to allow a parish to exist there (Khrapovitskii 81). At the second meeting on November 9/22, 1920, Archbishop Anastasii (Gribanovskii) of Kishinev and Khotin was added to the HCA, and at the third meeting of the HCA it was resolved to contact the Patriarchate of Constantinople for an official decision on the canonical status of the HCA. The Patriarchate of Constantinople presented Metropolitan Antonii with the following statement: “Under your guidance the Patriarchate authorizes every undertaking, for the Patriarchate knows that Your Eminence will not commit any uncanonical act” (Hilko 8). On December 22, 1920, the Patriarchate of Constantinople presented the Russian Hierarchs the following gramota (№ 9084): “To the Russian Hierarchs has been vested the authority over the Russian Orthodox refugees, in order to fulfill all the needs of Church and religion for the comfort and reassurance of the Russian Orthodox refugees” (Khrapovitskii 82). Metropolitan Antonii was also invited to come to Antioch by Patriarch Gregory VI of Antioch, an old friend, but the Metropolitan declined in order to stay with his flock (82).

The Move to Yugoslavia

Soon after the Russian émigrés arrived in Constantinople, the HCA began working on their next move to Belgrade. This task was given to E.I. Makharoblidze, the secretary of the HCA. Metropolitan Antonii was assured by the Serbian Church a place to live in the Serbian Patriarchal Palace in Sremski Karlovtsi and the other Russian Bishops were promised residence in Serbian monasteries. In the Spring of 1921, Metropolitan Antonii left for Serbia (Khrapovitskii 83). In its meetings on April 6/19 and 8/21, 1921, the HCA came to its final decision to move to Serbia. Their reasons included the following: 1) the majority of Russian émigrés were in Serbia[21]5 On January 23/February 5, 1920, the first five Russian bishops had arrived in Serbia (Khrapovitskii 83). Of these five bishops, one was Archbishop Evlogii. In August of 1920, Archbishop Evlogii was … Continue reading, 2) Serbia is the center of the Balkans which would facilitate communication, 3) Serbia was where the most Russian Bishops were in one place, 4) in Serbia was to be found a number of the Russian educated people, 5) the commanders of the Russian Army were all either in Serbia or planned to move there in the following months, 6) an undefined and transparent relationship could be found in Constantinople between the Russians and the Turkish Army, 7) the transparent relationship (with the Turkish Army) was aggravating the relationship of other Western-European nations towards the Russians, weakening their relations, and 8) the HCA would be able to unite with its president, Metropolitan Antonii who was already in Serbia. And so, the HCA moved to Serbia, convening for its first meeting on July 9/22, 1921 (Rklitskii, Vol. 5, 23-24).

The building in Sremski Karlovtsi occupied from 1922 to 1926 by General P.N.Wrangel. Photo: https://kromni.livejournal.com/204704.html

The HCA was very grateful for the hospitality of the Patriarchate of Constantinople. However, it is evident that the Greeks understood their hospitality to mean accepting the HCA into the jurisdiction of the Patriarchate of Constantinople, while the HCA soon neglected that issue when they decided to move to Serbia. While still in Constantinople, the HCA acted with the blessing of the Patriarchate. For example, in the archives of the ROCA in New York, there is a protocol about the tonsuring of a reader in one of the Russian churches in Constantinople. The HCA blessed the tonsuring, yet first asked for the permission of the Patriarchate first (Protocol No. 19 of the HCA, March 9/22, 1921. Archive of the ROCA). Also, the HCA confirmed all divorces only with the permission and advice of the Patriarchate of Constantinople (Protocol No. 22 No date found. Archive of the ROCA). However, when the HCA left Constantinople, it did not seek the advice of the Patriarchate but rather decided to simply inform the Patriarchate of the planned move to Yugoslavia (Protocol No. 23, April 29/May 12, 1921. Archive of the ROCA). The basis for these later actions is justified by the writings of Sergei Viktorovich Troitskii who wrote that no church can be in submission to two church bodies at one time (Troitskii, S.V. Letter to the Chairman of the Hierarchical Synod of the ROCA. July 20, August 2, 1939. Archive of the ROCA). He writes, “Since the Church of Constantinople and the Church of Russia are two different bodies, which are in an administrative relationship self-ruling bodies, Orthodox Canon Law does not allow dependence on two Churches” (Troitskii, S.V. Letter to the Chairman of the Hierarchical Synod of the ROCA. July 20, August 2, 1939. Archive of the ROCA). Moreover, Patriarch Tikhon gave his blessing to the HCA despite its location within the canonical territory of the Patriarchate of Constantinople (Gubonin 261).

Henceforth, allowing the Russians to come to Serbia was not an easy decision for the Serbian Government. Nonetheless, the Serbs took their chances and welcomed the Russians. As soon as the hierarchs had arrived, Metropolitan Dimitrii invited all the bishops for dinner to welcome them and show his compassion. On the following day, the bishops were invited to the Royal Palace for dinner with the successor to the Serbian Royal Throne, Prince Alexander, thus receiving a warm welcome from the Serbian Church and the Yugoslav State (Khrapovitskii 83).

In Yugoslavia, the Serbian intelligentsia was shocked by the poor material situation of the Russian intelligentsia, but this did not prevent them from respecting their level of knowledge and capabilities (Maevskii 12). However, the Serbian intelligentsia was dismayed with the taking of power in Russia by the Bolsheviks, seeing it to be completely contrary to the intelligentsia’s education in Western Europe. Nonetheless, this was put aside and the Serbians took in the Russians of all walks of life, having compassion on their brother Slavs from Russia (Rklitskii 30).

The Council of the SOC and the All-Diaspora Council of the ROCA

On August 18/31, 1921, the Serbian Orthodox Church held a council. At this meeting, the Hierarchs discussed the status of the Russian Church in Exile[22]6 In the 1920’s, the ROCA is referred to in the Archives of the SOC at the Serbian Patriarchate in Belgrade as “Ruska Tsrkva u izgnanstvu” (The Russian Church in Exile), as well as “Sremska … Continue reading where the existence of the Russian Church was given the blessing to exist in Yugoslavia. The act (No. 31) stated: P.E. [Preosveshteni Episkop – The Very Most Reverend, Bishop] Jefrem, Bishop of Zhicha as the reporter, reports about the request of V.M. [Visokopreosveshteni Mitropolit – The Very Most Reverend, Metropolitan] Antoni, and he himself wishing that the Russian Church be helped as much as possible, finds that the request as a whole could not be accepted, but he reads a suggestion of the 4th section / minutes of its session from the 29th of this month which says:

The Holy Hierarchal Synod, having considered the proposals of V.M. [Visokopreosveshteni Mitropolit – The Very Most Reverend, Metropolitan] of Kiev and Galitsia, Lord Antonii, and of the Russian Archimandrite Kirill, states his readiness to care for the exiled Russian people and their spiritual needs from now on, as it has been done until this time. The Holy Hierarchical Synod will from now on, as until now, go out of its way to help the exiled Hierarchs, Deacons and Priests, and according to need and its abilities, it will receive them into the Serbian Church Service.

The Holy Hierarchal Synod is willing to receive under its protection the Higher Russian Church Administration, under whose dominion the following things would belong:

1. Jurisdiction over Russian clergy outside of our country and that Russian clergy within our country which is not in parochial or state-educational service, as well as over military clergy of the Russian army which is not in the Serbian Church service;

2. Divorce proceedings of Russian refugees.

After the speeches of V.M.G. [Visokopreosveshteni Mitropoliti Gospodina – The Very Most Reverend, Metropolitan Lords] Gavrilo and Varnava, and P.E. [Preosveshteni Episkop – The Very Most Reverend, Bishop] Nikolaj [Velimirovich], the suggestion of the 4th section, concerning the administration of Russian refugees, was approved unanimously (Patriarchal Archive of the SOC. Minutes from the 4th regular assembly of the Holy Hierarchal Synod of the Serbian Orthodox Church, held on August 18/31, 1921, in Sremski Karlovtsi).

According to Sergei Viktorovich Troitskii, this act of the SOC is the foundation of all the actions of the Russian Church in Yugoslavia (Troitskii 107). Later, on November 23/December 6, 1927, another council of the SOC declared the following: “According to the canons of the Holy Orthodox Church, when an Orthodox episcopate along with its flock endures persecution and is forced into exile onto the territory of another Church it has the right to have an independent organization and administration; in accordance with this, such a right must be recognized by the Russian Church hierarchy on the territory of the Serbian Church, naturally under the protection and supervision of the Serbian Church” (Pol’skii 126).

On September 10/23, 1921, the HCA met in Sremski Karlovtsi for one of its general meetings. At the meeting, the decision of the Serbian Church in the name of Patriarch Dimitrii was accepted with the following decision, stating: “The meaningful statement of His Holiness, the Patriarch of Serbia is to be put into consideration and use” (“Opredeleniia”. Tserkovnyia Vedomosti, No. 2 1922: 8-9)[23]7 It is interesting to note that the HCA, at its next meeting on January 4/17, 1922, read the statement of the SOC about the opening of a diocese in North America. This statement of Patriarch … Continue reading

On July 17/30, 1921, the HCA expressed to Patriarch Dimitrii its desire to hold an assembly in the following letter:

The Higher Russian Church Authority abroad, conscious of the benefit and necessity of similar preliminary meetings in different countries, appeal in this way to Your Holiness with the request that You permit a Russian Church assembly and that it be in Serbia, and that You would give Your prayerful archpastoral and graceful blessing on this undertaking, and in the same manner would send Your own representatives to this Assembly (Letter No. 484. July 17/30, 1921. Patriarchal Archive of the SOC).

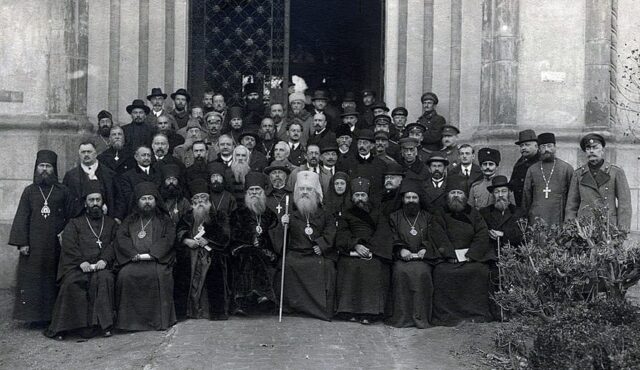

Patriarch Dimitrii gave his blessing and the Russian Church held its first All-Diaspora Council which lasted from November 8/21, of 1921 until November 20/December 3, 1921 (Deianiia Russkago Vsezagranichnago Tserkovnago Sobora, Title Page). There were officially 155 participants at the Council (Seide, Part I, Ch. 3, 33). Patriarch Dimitrii was given the title of honorary president of the Council. All the Serbian bishops were invited to the council, yet only three, including the Patriarch, were present. The other two were Metropolitan Ilarion of Tuzla and Bishop Maksimilian of Sremska Mitrovitsa (Deianiia Russkago Vsezagranichnago Tserkovnago Sobora 8 & 15). Eight other Serbian bishops sent their greetings. The Bulgarian Orthodox Church was also represented for one day of the proceedings by Metropolitan Stefan of Sofia (Seide, Part I, Ch. 3, 33-34). Priest Georg Seide writes in his manuscript The History of the Russian Church Abroad the following about the council:

Members of the First Pan-Diaspora Council. Sremski-Karlovtsi, 1921

Originally, the Council was convened as a “ecclesiastical assembly” for the Russian emigration. The assembly did not at first claim to be a Council. The Resolution of July[24]8 Refers to Letter No. 484 of July 17/30, 1921 quoted above. spoke definitively of a “convocation of an ecclesiastical assembly abroad.” The participants, who included Archbishop Evlogy, spoke as much of a “religious assembly” as of a “Council.” The Serbian Patriarch Dimitry and King Alexander called the assembly a “Council” in their messages of greeting. A group of participants moved that the assembly be considered a “Council”; this motion was passed.

Only a few months after the council on April 15/28, 1922, the Serbian Patriarchate received a letter (No. 3902) from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes in regards to the status of the ROCA:

The ministry of foreign affairs is honored to request the Patriarchate to report about the conditions under which the independent Russian Church Administration in Karlovtsi has been recognized by the Patriarchate, within what boundaries its authority lay, as well as whether the recognition came in agreement with our government.

The ministry of foreign affairs poses this question because a report came from our consul in Athens, in which he says that the Russian consul in Athens received a letter from the Russian Metropolitan Dimitrii from here (who is abiding with us), who asks that the Greek government be notified that the Russian Administration in Karlovtsi is the only Church authority for all Church matters – dogmatic and personal (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. Letter to the Patriarchate of the Serbian Orthodox Church. April 22/May 5, 1922. Russian Orthodox Church Abroad File. Archive of the SOC, Belgrade.).

Within one week, the Serbian Patriarchate replied by the order of Patriarch Dimitrii with the following letter (No. 31):

The Russian Church Administration in Sremski Karlovtsi exists with the blessing of His Holiness the Patriarch of Moscow, exclusively for the church affairs of the colonies of Russian Orthodox refugees, which are dispersed all over Europe. This Church Administration takes care of the liturgical life and administration of sacraments to the refugees, of keeping the church discipline among Russian clergy, of church courts (church-law issues) among the refugees and generally of fulfilling their religious needs.

As far as the Patriarchate knows, such Church Administrations also exist in America, Asia and Africa.

Our Church has, of course, approved Russian Church Administration’s performing of these businesses within Russian colonies. If the Russian Church Administration in Athens has requested an approval to perform such work among the Russian refugees in Greece, then it has certainly contacted their Church Administration, just as it has done here with us.

The Lord Minister-President is also aware of the happenings within the Russian Church Administration as well as of the gatherings [(communities)] of their members (Patriarchate of the Serbian Orthodox Church. Letter to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. April 22/May 5, 1922. Russian Orthodox Church Abroad File. Archive of the SOC, Belgrade.).

On March 3.16, 1922, Patriarch Dimitrii was sent a gramota from Patriarch Tikhon of Russia. In the gramota, the Patriarch thanks Patriarch Dimitrii for his hospitality to the Russian émigrés:

Our heart is even more filled with the feeling of joy and thankfulness to Your Beatitude, that we feel all the living good that was done and is being done by You in regards to the Russian exiles – the bishops, clerics and laymen, who were left outside the borders of their native land due to the power of the events, and found themselves the hospitality and asylum within the borders of the Serbian Patriarchate. May the Lord return to You a hundred fold for this blessed work.

May the days of your Patriarchal service be blessed (“Gramota”. Tserkovnyia Vedomosti. No. 5 1922: 3).

Interestingly enough, in Patriarch Dimitrii’s response to Patriarch Tikhon, no mention is made of the Russian émigrés (“Gramota”. Tserkovnyia Vedomosti. No. 8-9 1922: 1-4).

Other General Relations throughout the Patriarchal Rule of Patriarch Dimitrii of Serbia

During the 1920’s, there were many minor and major signs of support and charity within the relationship of the SOC and the ROCA, the SOC always upholding her commitment of support to the Russian Church émigrés. The SOC even ordained a bishop for the Russian Church. “In the Summer of 1921, Metropolitan Evlogii received a letter from Patriarch Tikhon in which the desire for a worthy bishop to be found abroad for Alaska for a self-governing Aleutian Diocese established by the All-Russian Council, was expressed. Metropolitan Evlogii informed the Higher Church Authority about it, which assigned Archimandrite Antonii to the cathedra [or diocese] of Bishop of the Aleuts” (“Episkop Antonii Aleutskii”. Tserkovnaia Zhizn’. No. 4 1934: 66). Bishop Antonii Aleutskii was ordained in July of 1921 by Patriarch Dimitrii, Metropolitan Antonii and Bishop Maksimilian (SOC) (66).

Serbian clergy would serve with ROCA clergy on other sorts of occasions as well. One example was on March 15, 1923, the Serbian Bishop Irinei[25]9 Bishop Irinei of Novi Sad finished at the Theological Academy of Moscow (Sava 199). It is interesting to point out that he was the bishop who was sent to Sofia, Bulgaria from the SOC to serve with … Continue reading served a memorial service in the Russian Church with other Russian clergy in Novi Sad for the “Tsar-Martyrs” Aleksandr II and Nikolai II (“Panikhida po Tsariam-Muchenikam.” Tserkovnyia Vedomosti. No. 7-8 1923: 9). The Russian bishops would also be invited to participate in the celebration of Patriarch Dimitrii’s slava. At one of the slavas of Patriarch Dimitrii, Metropolitan Antonii was presented with 2,000 dinars for the needs of especially needy Russian immigrants. This was presented by S.N. Paleolog, the Government Commissioner for the Organization of the Russian Refugees on behalf of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (“Den’ Slavy Patriarkha Serbskago.” Tserkovnyia Vedomosti. No. 21-22 1924: 9). Patriarch Dimitrii would also show his good will to the Russian émigrés around the festal times of the Church. On the first day of Pascha in 1924, Patriarch Dimitrii invited the 34 poorest Russian immigrants to eat with him. On the second day, he invited other representatives of the Russian émigrés, and on May 23, 1924, he invited S.N. Paleolog to discuss the situation of the Russian refugees (“Vnimanie Sviateishago Patriarha Serbskago k russkim bezhentsam.” Tserkovnyia Vedomosti. No. 9-10 1924: 14). Patriarch Dimitrii would also be involved in the founding of different church organizations. One instance is when he blessed for the starting of the “Russian Orthodox Brotherhood in Memory of Fr. John of Kronstadt” (“Patriarshee blagoslovenie Pastyrskomu Bratstvu.” Tserkovnyia Vedomosti. No. 9-10 1924: 14).

Also, when important events were taking place in the SOC, representatives of the ROCA would be called to be present. When a delegation from the Jerusalem Patriarchate was in Sremski Karlovtsi, 14 bishops were present from among the Russian hierarchy. At this event, the Serbian Patriarch Dimitrii was presented with the Order of the Panagios Tafos from Metropolitan Dosifei of Sebaste (“Torzhestvo v Sremskikh Karlovtsakh.” Tserkovnyia Vedomosti. No. 19-20 1924: 20). The SOC would also take up collections for the Russian Church and cause. In 1930, the SOC called for a collection for the Russian church in Brussels, which was to be built in memory of the Czar-Martyr Nicholas II. This collection was done in Serbian churches with the blessing of the local diocesan bishop (“Opredelenie Sv. Arkhiereiskago Sobora Serbskoi Pravoslavnoi Tserkvi.” Tserkovnyia Vedomosti. No 5-6 1930:

3). The Serbian People would in general simply send money to help the Russian cause. In a donation sent for the Russian Church in Berlin, one Serbian Sergeant-General named Fadin Khairorich wrote that “the desire for a collection of donations was awaken by gratitude for that which all feel, in relation to the sacrifice of the Russian mercenaries who fought for our [Serbian] liberation from the Turkish yoke” (“Trogatel’noe otnoshenie serbov k russkomu hramu v Berline.” Tserkovnyia Vedomosti. No 5-6 1930: 11). The Serbian Patriarch Dimitrii also made an appeal to all the other Orthodox Churches on behalf of the suffering Russian land (“Obrashchenie.” Tserkovnyia Vedomosti. No 3-4 1930: 2). He wrote:

The Serbian Orthodox Church in its deep commiseration with the suffering of its sister Russian Orthodox church and her faithful, asks of its sisters – all Orthodox Churches, with the request that they would lift up prayers to the Lord God for the deliverance and salvation of the Russian Orthodox Church and our brotherly Russian People who find themselves in difficult temptations, even being threatened with their existence[26]10 It is interesting to note that this letter is addressed to all the autocephalous Orthodox Churches, as well as ROCA and the Carpatho-Russian Diocese, which were not autocephalous: “Appeal of His … Continue reading (2). Patriarch Dimitrii also informed Metropolitan Antonii about this document in an official letter (February 5/18, 1930. No. 458. Tserkovnyia Vedomosti. No. 3-4 1930: 3). Metropolitan Antonii replied with a letter of great thanks to the Patriarch of Serbia (February 15/28, 1930. No. 161. Tserkovnyia Vedomosti. No. 5-6 1930: 3). Patriarch Dimitrii would also give his blessing to major events in the ROCA. For example, when Metropolitan Antonii went to Palestine and Archbishop Feofan of Poltava was to act as the Temporary Chairman of the ROCA, Patriarch Dimitrii gave his blessing and wished Archbishop Feofan all the best (Patriarch Dimitrii. Letter to Archbishop Feofan. Tserkovnyia Vedomosti. No. 9-10 1924: 1).

Patriarch Dimitrii also gave his help and support to the Russians when unpleasant situations arose. In 1924, for example, there was a rumor that all the Eastern Patriarchs, including Patriarch Dimitrii of Serbia, felt that Patriarch Tikhon should be relieved of his duties as Patriarch of Russia. Patriarch Dimitrii was notified about this by Archbishop Feofan, the Temporary Chairman of the ROCA, and quickly replied, assuring Archbishop Feofan that he, the Patriarch of Serbia, had nothing to do with this rumor and still regarded Patriarch Tikhon as the Patriarch of Russia and commemorated him at services (Patriarch Dimitrii. Letter to Archbishop Feofan. Tserkovnyia Vedomosti. No. 17-18 1924: 2).

Bishop Mardarij, an alumnus of St. Petersburg Theological Academy, was glorified in 2017 a saint by diocese of the SOC in US

In 1926, Patriarch Dimitrii again showed his support to the Russians in Yugoslavia in a letter he wrote Metropolitan Antonii which stated that a new Russian church in Belgrade would be built for the Russians. This was in response to the veneration of the Chapel of St. Mark [27]11 This is the chapel that eventually became the Holy Trinity Russian Orthodox Church in Belgrade behind the Cathedral of St. Mark. The Serbs have a tradition of building a small chapel on the site … Continue reading in Belgrade by the Russians. The Russians were constantly coming to services there and asked that they hang a bell on the chapel. Because of such a large amount of Russians coming, the Patriarch felt it necessary to build another Russian church there (December 23, 1924/January 5, 1925. No. 4271. Tserkovnyia Vedomosti. No. 1-2 1926: 1).

Before the repose of Patriarch Dimitrii, he blessed for a gathering to be held in Belgrade in memory of the victims of the Bolshevik regime. The Serbian hierarchy supported this event which took place on February 10, 1930. Along with Metropolitan Antonii and Bishops Feofan of Kursk and Sergii of the Black Sea, Serbian bishops attended the gathering as well. They included Metropolitan Gavriil of Montenegro (the future Patriarch of Serbia), Bishop Ioann of Mostar, Bishop Iosif[28]12 Bishop Iosif of Bitola studied in Kiev at the Theological Academy there at the beginning of the Twentieth Century (Sava 261). of Bitola, Bishop Mardarii[29]13 Bishop Mardarii finshed the Theological Academy in St. Petersburg (Sava 307). of North America and Bishop Viktor of Skadar. The Serbian hierarchs offered their support to the suffering Russian people (“Belgradskoe sobranie v pamiati zhertv bol’shevitskago rezhima.” Tserkovnyia Vedomosti. No. 8 1930: 11).

It is also necessary to point out Metropolitan Antonii’s rank among the hierarchy of the SOC. He was not only respected by all, but was given the honor of serving as the highest Metropolitan in rank at all hierarchical services that were conducted in the SOC. Even at the funeral of Patriarch Dimitrii, Metropolitan Antonii served as the oldest in rank, leading the funeral ceremony (“Pogrebenie Sviateishago Patriarkha Dimitriia.” Tserkovnyia Vedomosti. No. 7 1930: 6). Although he was supposedly a guest, Metropolitan Antonii was regarded as a man in his own home. Unfortunately, Metropolitan Antonii, occasionally overextended the hospitality of the Serbs to himself. One instance of this is in regards to Archimandrite Kiprian (Kern). Archimandrite Kiprian was a cleric of the SOC under the Serbian Bishop Iosif and taught at a Serbian Theological Faculty; however, Archimandrite Kiprian was moved to the jurisdiction of the ROCA as if he were a cleric of the ROCA and not the SOC[30]14 Archimandrite Kiprian in his memoirs of Metropolitan Antonii seems to portray him (Metropolitan Antonii) as having acted contrary to the will of the Serbian Church. This portrayal seems incorrect … Continue reading service (Patriarchal Archive of the SOC. Minutes from the 4th regular assembly of the Holy Synod of Bishops of the Serbian Orthodox Church, held on August 18/31, 1921, in Sremski Karlovtsi).

Russian Monasteries in the Jurisdiction of the ROCA

As mentioned earlier, the Russian bishops who were living in Serbia were scattered throughout Serbian monasteries, mainly in the area between Belgrade and Novi Sad called Frushka Gora. For example, Archbishops Germogen (Maksimov) and Feofan (Gavrilov) were at Hopovo Monastery (Seide, Monasteries and Convents of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad, 48). Bishop Mikhail of Aleksandrov was living in monastery Grgeteg until his death in October of 1925 (Gramota No. 3405 from Patriarch Dimitrii to Metropolitan Antonii, Tserkovnyia Vedomosti, No. 19-20, 1925).

Metropolitan Anthony (Khrapovitsky) with the brotherhood of the Milkovo Monastery in Serbia. At the right hand of Metropolitan: Schema Archimandrite Ambrose (Kurganov), Hieroschemamonk Mark, Hieromonk Callistus. On the left: Bishop Tikhon (Troitsky, later Archbishop of San Francisco and Western America) and Archimandrite Theodosius, behind him the extreme left is the Hieormonk John (Maximovich, later Archbishop of San Francisco), and next to him Hieromonk Anthony (Sinkevich, later Archbishop of Los Angeles). In the lower left row in the center sits the novice Artemy (Medvedev, later Archbishop Anthony of San Francisco) Text by M. Woerl

In general, the Russian monastic spirit was not quenched by the movement of the Russian faithful to Yugoslavia. Two major monasteries filled with Russian monastics existed in Yugoslavia: the Convent of the Icon of the Mother of God of Lesna at Hopovo and the Milkovo Monastery near Lapovo. The Convent of the Icon of the Mother of God of Lesna was originally a Russian monastic community located in the Zhabskii Convent in the Kholmsk province near the Russian border in an area had many Uniates. Because of political pressure, it was impossible for the nuns to remain there. At the sisterhood’s request, an invitation from the King of Serbia and the Serbian Patriarch was received and accepted by the community in 1920 (Seide, Monasteries and Convents of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad, 43 & 47). “The invitation was made in the hopes that the sisterhood might help inspire a rebirth of monasticism among Serbian women” (43). This move brought 62 nuns, including their Abbess Ekaterina and Assistant-Abbess Nina to the Hopovo Monastery located in the Frushka Gora region. The monastery soon opened an orphanage which was supported by Serbian and Russian families for the aid of Russian immigrants. Throughout the existence of the sisterhood at Hopovo monastery, it helped with the establishment of 32 Serbian convents, the sisters having gone out to form new monastic communities and often becoming the abbesses of them. The sisterhood remained in Hopovo until 1950 when it was forced to move to France because of political distress within the new communist Yugoslav Government. The other major Russian monastic community was the Milkovo Monastery near Lapovo. This community was refounded on the Morava River by the ascetic of the Optina Hermitage, Archimandrite Amvrosii (Kurganov). This monastery had about twenty-five monastics. Many of the Russian hierarchs would come and visit the spiritual center. The monastics were ascetical and diligent in their service to God. This monastery eventually provided the Russian Church Outside of Russia with a number of bishops, including Archbishops Antonii (Bartoshevich) and Antonii (Medvedev) and Bishop Leontii (Bartoshevich) (47-52).The Russians also had an effect on the Serbian monastery Visoko-Dechanska Lavra which was founded by Stefan Nemania in the region of Kosovo and Metohiia, near the river Bistritsa. The monastery was already being spiritually run by Russians when the émigrés had arrived, but the influx of Russians only contributed to the situation. Because of the constant pressure put on the monastery by the Albanians and Turks against the Serbian monastics, the Serbs were forced to hand over the monastery into the spiritual protection of the Russian monastery of St. John Chrysostom on Mount Athos. Some of the Russian abbots were Fathers Arsenii and Varsonofii. At the beginning of World War II, the abbot of the monastery was Bishop Mitrofan of Kharkov. After the death of Metropolitan Antonii (Khrapovitskii), the Metropolitan’s former cell-attendant Archimandrite Feodosii (Mel’nik) became abbot of the monastery. Archimandrite Feodosii remained abbot of the monastery as a cleric of the SOC until 1957 when he reposed. Monastery leadership was then returned to native Serbians (Paganuzzi “Vysoko-Dechanskaia Lavra”. Pravoslavnaia Zhizn’. No. 8 1976: 22-23).The Serbian Church also had jurisdiction over some of the Russian monasteries outside the borders of Yugoslavia. The most well known of these monasteries is the monastery of St. Job of Pochaev in the Carpathian Mountains, especially for its missionary activity with its printing of church books. The monastery printshop was founded and run by Archimandrite Vitalii (Maksimenko). In the early 1920’s, Archimandrite Vitalii was given a blessing by Patriarch Dimitrii of Serbia to print books for the Russian émigrés in Serbia and abroad. This was undertaken in the monastery Grgeteg in the Frushka Gora region of Serbia. It was very difficult for Archimandrite Vitalii in Grgeteg because, according to Patriarch Dimitrii’s blessing, he was not allowed to have any helpers. Soon, Archimandrite Vitalii moved and eventually ended up in Vladimirovo, Slovakia. He established the monastery there, became the abbot and carried on the tradition of the Pochaev Monastery printshop, which he reestablished before World War I in Volynia. One of the printing presses in the new printshop was paid for mainly by the donations of the Serbian King Aleksandar I, Patriarch Varnava of Serbia and Metropolitan Iosif of Skoplje, as well as the Serbian people. In 1932, the printshop was blessed by Bishop Damaskin[31]15 Bishop Damaskin was a hierarch of the SOC. He completed the Theological Academy in St. Petersburg in 1917. He was later assigned to the Diocese of America and Canada (1938), then to the Diocese of … Continue reading of the Mukachevsko-Pryashev Diocese (Maksimenko 191-193). While Archimandrite Vitalii was abbot of the monastery, it was under the jurisdiction of the Serbian Church, as is evident by Bishop Damaskin’s presence, and its being the canonical territory of the SOC. After Archimandrite Vitalii was made bishop and sent to America and Archimandrite Serafim (Ivanov) became head of the monastery, a resistance was shown there towards Bishop Damaskin, and Archimandrite Serafim declared loyalty solely to the ROCA, refusing to recognize the monastery as part of the SOC and wanting to assure that it was a monastery of the ROCA (Monk Gorazd 126). From this monastery came forth much of the brotherhood of Holy Trinity Monastery in Jordanville, NY after World War II (Seide 58).

The Carpathian Diocese in the Jurisdiction of the SOC

The Carpathian Diocese itself was a part of the Patriarchate of Constantinople while the territory was a part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. In 1910, the then Archbishop Antonii (Khrapovitskii) of Zhitomir was given the title Exarch of Carpatho-Russia by Patriarch Ioakim III of Constantinople (Burega 218). In 1920, however, the diocese of Carpatho-Russia beckoned to the Serbian Church in Karlovtsi for assistance based on the archival evidence that Carpatho-Russia had once been under the jurisdiction of the Bishop of Zadar and the Metropolitanate of Karlovats (SOC). The jurisdiction of the SOC was recognized by the government of Czechoslovakia (Sava 136). In mid-1920, the Hierarchical Council of the SOC sent Bishop Dosifei of Nish[32]16 Bishop Dosifej of Nish studied in Kiev at the Theological Academy there, finishing in 1904 (Sava 175). to Czechoslovakia as its delegate, and he was accepted as an official delegate by the Czechoslovakian Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Burega 218-219). In 1921, Bishop Gorazd, a former Roman Catholic by the name of Machej Pavlik, was consecrated a bishop and appointed as bishop of the Czech-Moravian Diocese[33]17 In Sava’s book Srpski Jerarsi, it states that Bishop Gorazd was made Bishop of the Mukachev-Pryashev Diocese (Sava 136), but according to Monk Gorazd in Sud’by Pravoslavnoi Very v … Continue reading (Sava 136). At his hierarchical consecration, the Serbian Patriarch Dimitrii, Metropolitan Antonii (the First-Hierarch of the ROCA) and the Serbian Bishops Varnava and Iosif participated (Monk Gorazd 112). Bishop Gorazd was eventually martyred on September 4, 1942 by the Nazis (Sava 136). In 1923, Patriarch Meletios of Constantinople invited Archimandrite Savvatii from Prague to come to Constantinople and be consecrated a bishop. As a result, Archimandrite Savvatii was made Archbishop of Prague and All-Czechoslovakia on February 26, 1923. This caused conflict between the Churches of Constantinople and Serbia because the Serbian Church had already begun its organization of a diocese in Carpatho-Russia, as well as already having had a bishop there, i.e. Bishop Gorazd (Burega 226-228).Constantinople did not accept the actions of the Serbian Church. On April 2, 1923, Bishop Dosifei sent a letter to Metropolitan Evlogii (Georgievskii), the administrator of the Russian Orthodox parishes in Western Europe, in which Bishop Dosifei informed Metropolitan Evlogii that he was incapable of taking the regular care of the Orthodox Church in Carpatho-Russia and asked for Metropolitan Evlogii’s agreement to send Bishop Sergii (Korolev) of Kholm from Prague to Carpatho-Russia and to make him the administrator of the Carpatho-Russian Orthodox Church. Metropolitan Evlogii informed Bishop Dosifei that he was concerned about sending Bishop Sergii there without the consent of the Czechoslovakian government[34]He was evidently concerned about the reaction to this by the Patriarchate of Constantinople based on Bishop Dosifei’s reply. (226-228). Bishop Dosifei responded to this letter on May 2, 1923, stating: “My actions in the Republic of Czechoslovakia and in Carpatho-Russia are correct and received by me from the Holy Council of Bishops [of the SOC]. . . . All changes in this right can only be made with the consent of the Holy Council of Bishops. . . . I repeat, the acts of the Patriarch of Constantinople in regards to my current actions have no definitive power without the decision of our Holy Council of Bishops” (228). In the letter, Bishop Dosifei also included that the actions of Archbishop Savvatii were illegal because Bishop Dosifei was the legal bishop in Carpatho-Russia, and therefore there was nothing illegal about his own actions there in regards to the government. Metropolitan Evlogii was not in agreement with this since he had requested that Bishop Sergii keep brotherly relations with Archbishop Savvatii. This is found in his letter of March 19, 1923 to Bishop Sergii. He requested that all the Russian parishes in Czechoslovakia commemorate Archbishop Savvatii and he disregarded the act of the SOC in the establishment of the Carpatho-Russian Diocese as a part of the SOC. Archbishop Savvatii also accused the SOC in a letter to Patriarch Meletios of Constantinople of uniting with Russian émigré bishops in order to make Carpatho-Russia fall into its jurisdiction (228-229). At some point in 1923, Bishop Veniamin of Sevastopol’ was invited to Czechoslovakia by Archbishop Savvatii. According to the letter of Bishop Dosifei to Bishop Gorazd, Patriarch Dimitrii did not bless Bishop Veniamin to visit Archbishop Savvatii. However, Archbishop Savvatii affirms in a letter to the locum tenens of the Patriarchate of Constantinople, Metropolitan Nikolaos of Caesarea that Patriarch Dimitrii gave his blessing (230, 240-241). According to Bishop Dosifei in his letter to Bishop Gorazd, the exact words of Patriarch Dimitrii to Bishop Veniamin were the following: “Go wherever you want, but that which you are doing are intrigues” (240). Bishop Dosifei was in Carpatho-Russia once again in 1924 and continued his work there (262). Already in 1925, the Minister of Education in the Republic of Czechoslovakia accepted the diocese in control by the SOC as the official Orthodox Diocese. In this way, Archbishop Savvatii and the Patriarchate of Constantinople were defeated, yet they did not give up hope of gaining power there, having churches which were under the guidance of Archbishop Savvatii until World War II (262-263).In 1927, Bishop Irinei of Novi Sad was sent to administrate the diocese in Carpatho-Russia (201). In his first epistle to the flock, Bishop Irinei wrote: “We are now here representing the one, legal hierarchical power, which it is necessary to declare to all the Orthodox people,” i.e., the Serbian Orthodox Church (Monk Gorazd 125).After Bishop Irinei had spent a year in Carpatho-Russia, Bishop Serafim[35]19 Bishop Serafim of Rashko-Prizren finished the Theological Academy in Moscow in 1902. of the Rashko-Prizren Diocese was sent to administrate the diocese (125). He was there for one year, trying to regulate church affairs (Sava 442). In December of 1930, the Council of Bishops of the SOC decided that Bishop Iosif of Bitola be sent there. He himself felt that he should go in order to pay back the Russians for all the help they had shown the Serbian people throughout history (“Istoricheskoe Zasedanie Serbskago Sv. Sobora”. Pravoslavnaia Rus’. No. 24 1930: 2). He was thus given the title “Exarch of Carpatho-Russia” by the SOC. Hieromonk Iustin (Popovich) traveled with Bishop Iosif to the Carpathian Mountains. During their trip, Bishop Iosif received consent from the Czechoslovakian government on behalf of the Serbian Church to have a permanent hierarch in Carpatho-Russia with the title Mukachevsko-Priashevskii (Monk Gorazd 125-126). In 1931, Sindjel[36]20 The first award-title given to a priest-monk in the Serbian tradition. Damaskin (Grdanichki), former First-Secretary of the Serbian Patriarchate, was elected and consecrated Bishop of the Mukachev-Priashev Diocese (Sava 149). During Bishop Damaskin’s time as bishop of the Mukachev-Priashev Diocese, many people came back to Orthodoxy from the Uniatism of the Roman Catholic Church, churches being built throughout Carpatho-Russia for the faithful. In 1938, Bishop Vladimir (Rajich)[37]21 Bishop Vladimir of Rashko-Prizren finished the Theological Academy in Moscow (Sava 91). was sent from the SOC to the Mukachev-Pryashev Diocese (91).

A Reflection on the Serbian Reaction to Russian Immigrant Theology

St. John of Shanghai and Fr. Theodosii (Mel’nik), on the right with Serbian students of theology in Belgrade in the 1930s. Fr. Theodosii was an abbot of Decani monastery during WWII

Metropolitan Antonii (Khrapovitskii) is considered to be the great theologian of the ROCA. However, he received both positive and negative attention within the Serbian Church where he was living. Among the positive reactions are the words of Archimandrite Iustin (Popovich) who wrote that “In the latest times, no one has had such a powerful influence on Orthodox thought as Blessed Metropolitan Antonii. He took Orthodox thought that was mixed with the scholastic-rationalistic path and changed it into a grace-filled-ascetical path” (Rklitskii, Vol. X, 247). He writes that there is no one like Metropolitan Antonii, saying that his works are completely patristic based and compares him to the great ecumenical teachers of the Church, Sts. Basil the Great, Gregory the Theologian and John Chrysostom (245 & 250).In mid-1917, the then Archbishop Antonii (Khrapovitskii) published his most controversial theological work called “The Dogma of Redemption”. Here it is not necessary to go into great detail in regards to the essence of the work. Archimandrite Iustin does not contradict the writings of Metropolitan Antonii, but rather supports them in his book on dogmatic theology (Dogmatika Pravoslavne Tsrkve). Thus, great respect for Metropolitan Antonii’s theology was accepted by one of the most respected dogmatists of the Orthodox Church in the twentieth century. On the other hand, this work of Metropolitan Antonii was frowned upon by others. Archpriest Milosh Parenta, an academic who taught at the Belgrade Theological Faculty during the time that Metropolitan Antonii was in Yugoslavia, wrote a critical report on this document in 1926 in the official news organ of the SOC Glasnik, disapproving of the teaching, saying that in even just a few lines does the author write many anti-Orthodox teachings. Parenta claims that Metropolitan Antonii makes God the responsible one for man’s fall (Parenta, http://deistvo.chat.ru/06.htm).Part IV: The 1930’s – Patriarch Varnava and the Divisions in the Russian Orthodox Church.

The ROC (MP) and the ROCA