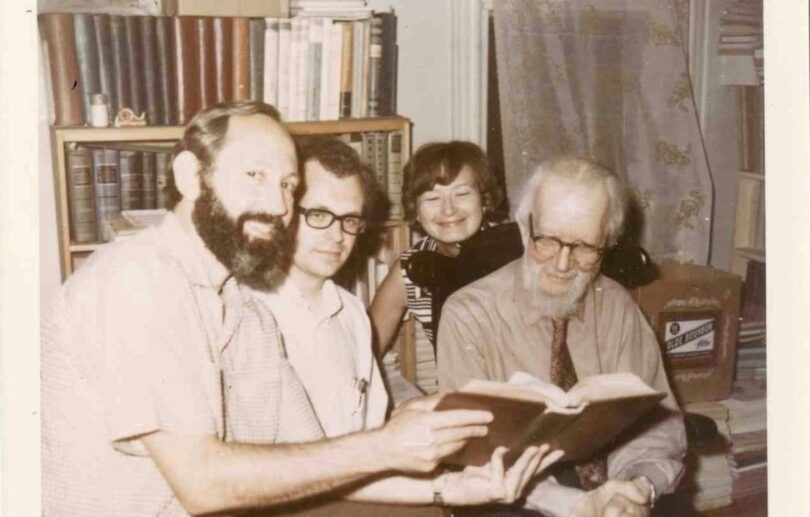

The two translated texts below are drawn from a publication of seventeen letters written by the theologian and archpriest Georges Florovsky to Alexis Klimoff over the period between 1966 and 1975. Klimoff, a graduate student at Yale at the beginning of his letter exchange with Florovsky, continued the correspondence into the early years of his college teaching career. The acquaintance dates from 1965, when Klimoff joined a team of translators who aimed to render Fr. Florovsky’s famous Puti russkogo bogosloviia into English. Although that project ultimately failed to be completed, several members of the translation team, including Klimoff, established friendly relations with Fr. Florovsky The excerpts below present Florovsky’s views on Church affairs in 1970 as well as his opinion on a central issue of Russian intellectual history. The original publication is titled “Pis’ma G.V. Florovskogo A.E. Klimovu (1966-1975).” It appears in Ezhegodnik Doma russkogo zarubezh’ia imeni Aleksandra Solzhenitsyna 2016 (Moscow: Dom Russkogo Zarubezh’ia, 2016), 581-608. The letter of March 20, 1970 appears on pp. 585-586; the letter of Feb. 24, 1975 on pp. 606-607. The letters have been translated by A. Klimoff and are published here with the permission of Dom Russkogo Zarubezh’ia. The endnotes have been composed by the translator.

March 20, 1970

(…) Autocephaly is a theme of great complexity.[1]Father Florovsky is here responding to a question concerning his opinion of the North American Metropolia’s quest to receive an official document (called a “tomos”) from the Moscow Patriarchate … Continue reading I won’t attempt to sort out the toxic mix formed by combining canonical considerations with emotional ones. It is difficult to question the “legitimacy” of the Moscow Patriarchate from the canonical point of view because the Patriarchate is recognized by all other autocephalous Orthodox Churches and also because it can argue that it is the historical successor of the unquestionably legitimate Patriarchate under Patriarch Tikhon.[2]Tikhon (Bellavin, 1865-1925, canonized in 1989), Patriarch of the Russian Orthodox Church 1917-1925. First Patriarch after a lengthy period (1700-1917) when the Russian Church functioned without the … Continue reading As for myself, I doubt that I could have followed Metropolitan Sergius; [3]Sergius (Stragorodskii, 1867-1944), Russian hierarch and theologian, in 1943-1944 appointed Patriarch of the Russian Orthodox Church. Florovsky is referring to his opposition to Sergius’s so-called … Continue reading I would have instead withdrawn from the world. There is a great deal that is unacceptable in the actions of the Moscow Patriarchate, but one should keep such criticism within bounds. One can surely admit that on psychological and moral grounds the Moscow Patriarchate has a questionable record. But it is not alone in this regard. The policies of Patriarch Athenagoras [4]Athenagoras (Spyrou, 1886-1972), Patriarch of Constantinople (1948-1972). His ecumenical activities, including cancelation in 1965 Partiarch Michael Kerlularios’ anathema against Papal legates … Continue reading are quite dubious and dangerous, but Constantinople nevertheless remains “canonical” as long as it steers clear of Greek megalomania. And on the other hand the canonical status of ROCOR is quote controversial, even from their own point of view. Specifically, a Church must be associated with a “territory,” while a diaspora and an emigration – the so-called “Russia Abroad [zarubezh’e]” – does not constitute a territory in the canonical sense. To grieve does not necessarily mean to condemn and to renounce. I agree that the campaign for autocephaly was conducted in morally tactless ways, a failing that remains prominent despite the canonical arguments. But one must not forget that while for “émigrés” like us, the autocephaly process is painful to contemplate, the overwhelming majority of “oldtime Americans” in the Metropolia (who have occasionally been wittily referred to as “Drevliane”[5] The Drevliane were a Slavic tribe mentioned in Russian chronicles. The name is based on the root drev- which means “ancient”.) don’t see any moral difficulties, and are only concerned with regularizing their canonical status so that they would no longer be accused of being schismatics. They have absolutely no interest in Moscow, but eagerly seek independence so as to have a means to defend themselves against the scorn of the Greeks whose aim has been to bring the Metropolia to heel.[6]The Ecumenical Patriarchate and its American Archdiocese did not recognize any other Church’s right to grant autocephaly and desired to bring the Metropolia into its own jurisdiction. For that … Continue reading The furious letter exchange concerning autocephaly in Novoe Russkoe Slovo [7] A Russian-language daily based in New York which published numerous polemical tracts concerning autocephaly in 1969-70. is profoundly depressing, inspired as it is by a spirit foreign to the Church and even to morality. It is the voice of political passion, resentment and hatred, one that entirely obscures the authentic problem. I cannot recall who noted that “history can be likened to the conjugation of irregular verbs.” The unfortunate fact is that history, including Church history both past and present, is not free of tragedy, antinomy and even ambiguity. The one thing that can be done is expressed thus:

“For the peace of the world and for the welfare of the Holy Churches of God let us pray to the Lord” [8] A litany in the Byzantine rite liturgy. and also: “bear ye one another’s burdens, and so fulfil the law of Christ.” [9] Apostle Paul’s Epistle to the Galatians, 6:2. <…>

February 24, 1975

(…)

Pushkin was right in calling Peter I [10] Peter I (1672-1725) is better known as “Peter the Great.” a revolutionary. I would add that he was also a terrorist of a special kind. In a certain sense his revolution succeeded, at least for two centuries. I don’t wish to idealize “Muscovite Russia.” To the extent that we can speak about cultural revolutions, this one had already begun before Peter.

One could refer to this as “The Crisis of Russian Byzantinism” (as I have named chapter 1 in my Ways of Russian Theology). But here’s the odd thing. In the West,

“byzantinism” proved to be a stimulus and a creative force, especially in the field of art. Without Giotto, Ducio and Cimabue there would have been no Renaissance. The Renaissance occurred in Moscow too – in the works of Rublev. The 16th century in Moscow was a period of creativity. Soviet scholarship has in a certain sense rehabilitated medieval Russia. But paradoxically enough the post-medieval period ushers in the beginning of disintegration. Western culture coming from Kiev and Poland proved victorious. In the 18th century the Church became culturally Latinized, seminaries switched to instruction in Latin, and this “Latin captivity” lasted almost to the time of the Crimean War. [11] 1853-1856. The lifeline of tradition was broken. As Herzen put it, “once one joins up with the Germans, it’s very difficult to make an exit”, or, as I say in Puti russkogo bogosloviia, “roots were replaced with foundation piles.” This eventually led to the collapse of the entire structure. Slavophilism in the end turned out to be a utopian dream, and long before 1917 Russia entered what can be called a “catastrophic phase.” I was one of the few who at the beginning of the 1920s started to speak of a “catastrophe-sensitive view of the world” to the great indignation of those whom the late Prince Nikolai Sergeevich Trubetskoy had called “old geezers.” [12]Florovsky is referring here to his involvement in the Eurasian movement together with the linguist Nikolai Trubetskoy (1890-1938) in the early 1920s and to several of his articles written at that … Continue reading “The spirit, not the body has been corrupted in our age, and men are desperately unhappy” wrote Tiutchev quite a few years ago, [13] Opening lines of Fedor Tiutchev’s 1851 poem titled “Our Century.” although this did not prevent him from dreaming of a “Universal empire” headed by the Russian tsar and the Pope of Rome. Vladimir Soloviev followed Tiutchev in this regard until the onset of a “catastrophic crisis” and the emergence of the Antichrist figure.[14] The reference is to “The Short Tale of the Antichrist” which is part of Vladimir Soloviev’s work titled Three Conversations About War, Progress and the End of History (1899). To add a curious note, a German scholar has recently proclaimed that Soloviev’s “Short Tale of the Antichrist” should today be required reading for everyone.

(…)

[The letter has an appendix in which Fr. Florovsky discusses some terminological issues unrelated to the text above. His comments on Ignatii Brianchaninov are of considerable interest](…) The turns of phrase used by Ignatii Brianchaninov [15]Ignatii (Brianchaninov, 1807-1867), a Russian bishop, theologian, canonized by the ROC in 1988 and ROCOR in 2001. Author of numerous works, mostly focused on issues of asceticism and the repudiation … Continue reading that troubled you are characteristic of him and they are of course not taken from the Scriptures. In my opinion, they have the air of Western “mystical” literature, despite all of Bishop Ignatii’s efforts to distance himself from “mysticism.” Unfortunately, I own only the first volume of his Works, while the major [relevant] texts are in the second volume, specifically on pp. 314-380. I am sending you some excerpts from Leonid Sokolov’s book titled Episkop Ignatii Brianchaninov, vol. II, Kiev 1915. Sokolov states in a footnote that Ignatii was here referring to Macarius of Egypt, discourse 4, but that text does not feature Ignatii’s phraseology and simply speaks of the manifestations of God to Moses and the prophets. The figures of the “Wanderer” [Strannik] or the “Guest” [Gost’] are not encountered in Macarius. By the way, we should get vol. II of Ignatii’s Works in Jordanville, as they have reprinted his writings. <…> Strangely enough, Ignatii has some “Romantic” traits such as the reading of “the books of nature” – an extraordinarily unusual feature in the context of Eastern Orthodox asceticism. No substantial study of Ignatii’s theology has yet appeared. Sokolov’s prolix tomes do not go beyond paraphrase, saying virtually nothing about the sources of Ignatii’s ideas and making no attempt to indicate his place in terms of various theological traditions. The late Professor Smolich [16]Smolich (“Smolitsch” in the German transcription, Igor, 1898-1970), historian of the Russian Church, for many years a professor in Berlin. Author of a two-volume history of the Russian Church up … Continue reading reproached me for what he considered a “completely erroneous” depiction of Ignatii. Ignatii was more to Smolich’s taste than Feofan the Recluse [Feofan Zatvornik] [17]Feofan (Govorov, 1815-1894), a Russian bishop, theologian, canonized by the Russian Orthodox Church in 1988 and by ROCOR in 2001. Known as “Feofan the Recluse” for retiring in order to dedicate … Continue reading or even Fr. John of Kronstadt.[18] Fr. John (Ioann Sergiev, best known as Ioann Kronshtadtskii, 1829-1909), highly popular Russian priest and writer on religious matters. Canonized in 1964 (ROCOR), in 1990 (ROC). For the English translation of Puti russkogo bogosloviia, my brief paragraph on Ignatii in the present Russian edition will have to be expanded, a task for which that second volume will be needed.

Alexis Klimoff, On the Sophiological Controversy of the 1930s

References

| ↵1 | Father Florovsky is here responding to a question concerning his opinion of the North American Metropolia’s quest to receive an official document (called a “tomos”) from the Moscow Patriarchate that would grant the Metropolia the status of a legitimate self-governing Church body. The tomos was in fact granted on April 19, 1970, transforming the Metropolia into The Orthodox Church in America (OCA), but this act was preceded by many months of bitter polemics concerning the moral appropriateness of turning to what critics charged was a “politically compromised” Church body in search of legitimacy. |

|---|---|

| ↵2 | Tikhon (Bellavin, 1865-1925, canonized in 1989), Patriarch of the Russian Orthodox Church 1917-1925. First Patriarch after a lengthy period (1700-1917) when the Russian Church functioned without the traditional patriarchal structure. |

| ↵3 | Sergius (Stragorodskii, 1867-1944), Russian hierarch and theologian, in 1943-1944 appointed Patriarch of the Russian Orthodox Church. Florovsky is referring to his opposition to Sergius’s so-called Declaration of 1927 which announced the Church’s unconditional loyalty to the Soviet authorities. |

| ↵4 | Athenagoras (Spyrou, 1886-1972), Patriarch of Constantinople (1948-1972). His ecumenical activities, including cancelation in 1965 Partiarch Michael Kerlularios’ anathema against Papal legates (1054), was viewed with some alarm in the Orthodox world. |

| ↵5 | The Drevliane were a Slavic tribe mentioned in Russian chronicles. The name is based on the root drev- which means “ancient”. |

| ↵6 | The Ecumenical Patriarchate and its American Archdiocese did not recognize any other Church’s right to grant autocephaly and desired to bring the Metropolia into its own jurisdiction. For that reason it has not recognized the OCA. |

| ↵7 | A Russian-language daily based in New York which published numerous polemical tracts concerning autocephaly in 1969-70. |

| ↵8 | A litany in the Byzantine rite liturgy. |

| ↵9 | Apostle Paul’s Epistle to the Galatians, 6:2. |

| ↵10 | Peter I (1672-1725) is better known as “Peter the Great.” |

| ↵11 | 1853-1856. |

| ↵12 | Florovsky is referring here to his involvement in the Eurasian movement together with the linguist Nikolai Trubetskoy (1890-1938) in the early 1920s and to several of his articles written at that time. “Old geezers” is an attempt to render starye grymzy. This was Trubetskoy’s term for members of the old intelligentsia who disapproved of Eurasianism. |

| ↵13 | Opening lines of Fedor Tiutchev’s 1851 poem titled “Our Century.” |

| ↵14 | The reference is to “The Short Tale of the Antichrist” which is part of Vladimir Soloviev’s work titled Three Conversations About War, Progress and the End of History (1899). |

| ↵15 | Ignatii (Brianchaninov, 1807-1867), a Russian bishop, theologian, canonized by the ROC in 1988 and ROCOR in 2001. Author of numerous works, mostly focused on issues of asceticism and the repudiation of Western spirituality. The reference to St. Ignatii was made by Florovsky in connection with the republication of Brianchaninov’s works undertaken by Holy Trinity Monastery in Jordanville, NY. |

| ↵16 | Smolich (“Smolitsch” in the German transcription, Igor, 1898-1970), historian of the Russian Church, for many years a professor in Berlin. Author of a two-volume history of the Russian Church up to 1917 (German ed. 1964-1991; Russian ed. 1997). |

| ↵17 | Feofan (Govorov, 1815-1894), a Russian bishop, theologian, canonized by the Russian Orthodox Church in 1988 and by ROCOR in 2001. Known as “Feofan the Recluse” for retiring in order to dedicate himself to writing on Church subjects and to engage in correspondence with numerous individuals seeking spiritual counsel. |

| ↵18 | Fr. John (Ioann Sergiev, best known as Ioann Kronshtadtskii, 1829-1909), highly popular Russian priest and writer on religious matters. Canonized in 1964 (ROCOR), in 1990 (ROC). |

Interesting comments by Florovsky. His erudition and extraordinary intellect undergird anything he says (which is why I find him so interesting). I wish he had speculated as to why Jordanville (of all places, he seems to imply) published St. Ignaty’s work. Fr. Georges, I think, was at his best when he was speculating about the meaning of history.