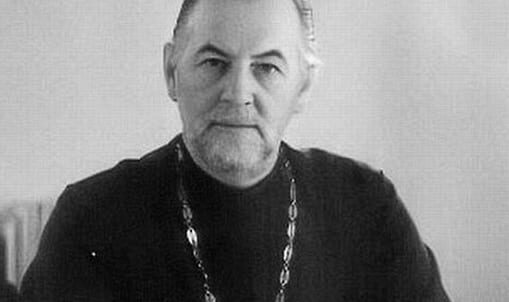

The Church Abroad has historically had strong reservations about ecumenism. For example, one may point to the “Sorrowful Epistles” of Metropolitan Philaret (Voznesensky). His First Epistle was written in response to the events of the 1969 assembly of the World Council of Churches in Uppsala, Sweden. Metropolitan Philaret cites a number of disturbing developments that, in his opinion, amount to a blurring of the boundaries of the Church. For example, he mentions that one Orthodox delegate called upon the “Church Universal” to bear witness before the world, apparently referring to the whole assembly. In Metropolitan Philaret’s eyes, this was an implicit admission of the “branch theory” of ecclesiology– in other words, an implication that Orthodoxy constitutes “the Church” only when it is considered together with the many heterodox denominations. He concludes that Orthodox participation in the ecumenical movement has crossed the line into heresy. [1]Metropolitan Philaret (Voznesensky), “The First Sorrowful Epistle,” 27 July 1969, ROCOR Studies: Historical Studies of the Russian Church Abroad, … Continue reading Although Metropolitan Philaret raises a valid concern, it is perhaps unfair to paint the entire phenomenon of ecumenism with the brush of heresy. Fr. Alexander Schmemann offers poignant insight on this question, writing that “the unity of ‘Ecumenism’ is a myth which makes it impossible to use this term as the name of a ‘heresy.’ There is good ‘ecumenism’ and bad ‘ecumenism.”’ [2]Alexander Schmemann, “On the ‘Sorrowful Epistle of Metropolitan Philaret,” The Orthodox Church, vol. unknown (1969), Protopresbyter Alexander Schmemann, … Continue reading Fr. Alexander himself was an active participant in the ecumenical movement, and he offers a very nuanced perspective. He had high hopes for the ecumenical movement, seeing it as an opportunity to bear witness to the Orthodox faith and to seek cooperation with other Christians in the struggle against secularism. However, he never lost sight of the substantial doctrinal disagreements between Orthodox and heterodox Christianity, and he firmly resisted any attempt to gloss over the differences between the two. This paper seeks to more closely define Fr. Alexander’s opinion of the ecumenical movement, and, in doing so, challenge the notion that engagement with the ecumenical movement per se constitutes heresy. I will argue that Fr. Alexander’s life and work demonstrate that it is possible to participate in constructive dialogue with heterodox Christians without giving in to problematic forms of ecumenism.

From the very beginning, Fr. Alexander hoped that much good would come out of the ecumenical encounter. He saw the ecumenical movement first and foremost as an opportunity to witness to the truth of Orthodox Christianity – an opportunity that, in his opinion, could not be neglected. In his day as in ours, the Orthodox faith remained largely unknown among people living in the West. Many Westerners, doubtless, would have never even heard of the Orthodox Church. The ecumenical encounter gives the Orthodox Church a chance to manifest itself and make a case for its claim to possess the truth. As Fr. Alexander writes:

It has always been the consensus of Orthodox theologians that their participation in the ecumenical movement has as its goal to bring an Orthodox witness to the non-Orthodox and there is no reason to deny that this implies the idea of conversion to Orthodoxy. [emphasis added] … Our “mission” then remains the same: to make Orthodoxy known, understood and, with God’s help, accepted in the West. [3] Alexander Schmemann, Church, World, Mission: Reflections on Orthodoxy in the West (Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1979), 123.

Ideally, then, the witness of the Orthodox Church to the ecumenical movement will also serve a missionary purpose. As the one true faith, the Orthodox Church must communicate its teaching to heterodox Christians to give them the opportunity to receive the fullness of the life in Christ that is possible only in the Orthodox Church. In other words, the Orthodox must participate in the ecumenical movement because their participation will facilitate the conversion of heterodox Christians to the Orthodox faith. To this end, engagement with Western Christianity and with Western culture in general simply cannot be avoided. As Fr. Alexander writes elsewhere:

I know that there are those Orthodox who affirm and preach that the Orthodox can and must live in the West without any “reference” to the Western culture except that of a total negation, to live in fact as if the West did not exist, for it is totally corrupt, heretical and sick beyond repair. … What these “super-Orthodox” do not know, of course, is that their attitude reflects precisely the ultimate surrender to the West which they abhor: that in their ideology Orthodoxy is being transformed for the first time into that which it has never been– a sect [emphasis original], which is by definition the refusal of the catholic vocation of the Church [emphasis added]. [4] Schmemann, Church, World, Mission, 207.

Here, Fr. Alexander is criticizing the tendency of some Orthodox toward isolationism. Orthodox truth must be preserved, but not at the expense of spreading the faith. The Church is called to preach the Gospel to all nations– if this is to happen, then the faithful must be willing to have a dialogue with those on the outside.

Secondarily, Fr Alexander saw the ecumenical movement as an opportunity for Christians to offer a united witness against the rising tide of secularism. Commenting on the state of the world in the 1950s, he writes that on top of the persecution of Christianity under communist regimes, “The situation is not better in the countries which still enjoy freedom of religion. Everywhere Christians have become a minority, surrounded by either indifference and materialism, or by active anti-Christian ideologies, philosophies and ways of life.” [5] Alexander Schmemann, “Notes on Evanston,” St. Vladimir’s Theological Quarterly 3, no. 1-2 (1954-1955), 58-60, https://www.schmemann.org/byhim/evanston.html accessed December 31, 2022. In the face of a gradually de-Christianizing world, Fr. Alexander speaks hopefully of the World Council of Church’s common desire to “reconquer the world for Christ.”’ [6] Schmemann, “Notes on Evanston,” St. Vladimir’s Theological Quarterly 3, no. 1-2 (1954-1955), 58-60, https://www.schmemann.org/byhim/evanston.html, accessed December 31, 2022. Fr. Alexander’s family fled from Soviet Russia, and he found himself living in an increasingly-secular West – it only makes sense that he would think it advantageous to seek allies among other Christian groups.

Consistent with his optimism for the ecumenical movement, Fr. Alexander sought constructive engagement with the heterodox throughout his life. For example, he was a participant at the very first assembly of the World Council of Churches in Amsterdam in 1948, [7] Schmemann, Church, World, Mission, 199. and he was also an Orthodox observer at the Second Vatican Council. He engaged constantly with Western theological scholarship, [8] Andrew Louth, Modern Orthodox Thinkers: from the Philokalia to the Present (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2015), 195-196. and he frequently gave guest lectures at heterodox seminaries. [9] Alexander Schmemann, The Journals of Father Alexander Schmemann 1973-1983, trans. Juliana Schmemann (Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2000), 104, 109, 122, 133. His engagement bore remarkable fruit during his lifetime, as revealed by an exceptional passage from his journals:

Yesterday morning I had a phone call from Bruce Rigdon in Chicago, who incited me in 1963 to write For the Life of the World. He has become an important man in ecumenism and in the Presbyterian Church. The Presbyterians are now– says he– revising their teaching about the sacraments, especially about baptism. Their main help is my Of Water and the Spirit. [emphasis added] He invited me to come to a conference in October where the revision will be debated “on a high level.” He says he is constantly rereading my books, that they changed and defined his theological conscience. [10] Schmemann, Journals, 322.

Rigdon may not have converted to Orthodoxy, but the fact that he pushed for his Church to redefine their sacramental theology along Orthodox lines is truly astonishing. This is an example of the hoped-for fruit of Fr. Alexander’s “good ecumenism.”

Fr. Alexander’s high hopes for the ecumenical movement were probably colored by his optimistic view of Western Christianity. In one article, he expresses his disappointment at the anti-Westernism that is occasionally expressed by Orthodox Christians:

It is sad and shocking to hear the West globally condemned and to see a condescending attitude toward the ‘poor Westerners’ on the part of young people who, more often than not, have not read Shakespeare and Cervantes, have never heard about St. Francis of Assisi or listened to Bach. [11] Schmemann, Church, World, Mission, 124.

While Orthodox Christians must remain true to their own faith, they must also be willing to see the good in the Christian West. Fr. Alexander’s sympathy is probably best explained by the simple fact that he lived almost his entire life in the West. “The Christian West: it is part of my childhood and youth,” [12] Schmemann, Journals, 19. he reminisces. One of his formative childhood experiences was, in fact, witnessing a Roman Catholic mass in Paris:

During my school years in Paris, on my way to the Lycée Carnot, I would stop by the Church of St. Charles of Monceau for two or three minutes. And always, in this huge, dark church, at one of the altars, a silent Mass was being said. … Sometimes I think of the contrast: a noisy, proletarian rue Legendre … and this never-changing Mass (…a spot of light on the dark wall…)– one step, and one is in a totally different world. This contrast somehow determined in my religious experience the intuition that has never left me: the existence of two heterogeneous worlds, the presence in this world of something absolutely and totally “other.” This “other” illumines everything, in one way or another. Everything is related to it– the Church as the Kingdom of God among and inside us. … the street, as it was, acquired a new charm that was understandable and obvious only to me, who knew at that moment the Presence, the feast revealed in the Mass nearby. Everything became alive, intriguing: every storefront window, the face of every person I met, the concrete, tangible feeling of that moment, the relationship between the street, the weather, the houses, the people. This experience remains with me forever: a very strong sense of “life” in its physical, bodily reality, in the uniqueness of every minute and of its correlation with life’s reality. [13] Schmemann, Journals, 19-20.

Fr. Andrew Louth speculates that this experience contributed to Fr. Alexander’s lifelong interest in liturgical theology. [14] Louth, Modern Orthodox Thinkers, 200-201. It would be fair to conclude that these kinds of experiences also gave Fr. Alexander a lifelong appreciation for Western Christianity – an appreciation often expressed in his journals. He writes admiringly of the beauty of the Catholic mass and of his soft spot for Western Church hymns. [15] Schmemann, Journals, 40, 111, 199. With this background, one can perhaps better understand why Fr. Alexander saw so much potential for Orthodox participation in the ecumenical movement.

Despite his optimism, however, Fr. Alexander was not afraid to offer criticism of Western Christianity when he believed it was appropriate. His criticism extends not just to obvious doctrinal differences, but to the basic mindset of the West. In his opinion, the Christian West has lost its link with eschatological Kingdom of God. He writes of a Western Christian “schizophrenia,” a mindset caught between this world and the next, unable to bridge them. [16] Schmemann, Journals, 288. He suggests elsewhere that this problem is the product of a theology that can no longer account for Divine immanence. This immanence is only possible, he writes, through the Uncreated Energies of God – a uniquely Orthodox concept. [17] Schmemann, Church, World, Mission, 203-205. Both Protestantism and Catholicism are guilty of this, but they express it in different ways. Protestants, he writes, have done away with liturgical worship and have lost their link to paradise. As a result, they are content with seeking a comfortable life on earth. Catholics, on the other hand, often try to reestablish paradise on earth, making them susceptible to utopianism. [18] Schmemann, Journals, 125. In a nutshell, Fr. Alexander was concerned that Western Christianity may have replaced their hope for the eschatological Kingdom of God with mere social activism. [19] Schmemann, Journals, 122.

Because of the very substantial differences between Orthodox and Western theology, Fr. Alexander believed that the ecumenical encounter must constitute a confrontation of doctrinal errors. However, he often lamented that the World Council of Churches did not share his approach, and this would prove to be one of his greatest frustrations with the ecumenical movement:

And if in the Orthodox understanding, the ecumenical movement was to be centered on an ultimate choice between truth and heresy, the Western presupposition of it was that ultimately all “choices” are to be integrated into one synthesis, in which all are mutually enriching and complementary to one another. The word “heresy,” in fact, is absent even today from the ecumenical vocabulary, and does not exist even as a possibility. [20] Alexander Schmemann, “Moment of Truth for Orthodoxy” in Unity in Mid-Career: an Ecumenical Critique, ed. Keith R. Bridston and Walter D. Wagoner (New York, NY: The Macmillan Company, 1963), 53-54. [emphasis original]

In Fr. Alexander’s opinion, the World Council of Churches operated under the assumption that Christendom could only be enriched by the synthesis of the many Christian denominations. This was a presupposition that he could not accept because it implied that each denomination was equally valid– in other words, it did not acknowledge the danger posed by heresy. Whereas Fr. Alexander believed that the ecumenical encounter should be motivated by the common search for truth, he believed that the World Council of Churches sought unity at the expense of truth. There was a very real risk, in Fr. Alexander’s mind, that the ecumenical movement could collapse into a meaningless relativism where the categories of objective truth and error could not be applied. He repeats his frustrations in a 1962 letter to Fr. George Grabbe (later Bishop Gregory):

I am increasingly convinced that the Orthodox should leave the WCC and I plan to write about this. I feel the WWC’s main failing is their denial of even the possibility of heresy, i.e., doctrinal errors. [emphasis added] In this, modern Protestants depart from the position of their teachers, such as Luther and Calvin. They at least affirmed some things and refuted others. Ecumenism is dangerous to the Orthodox when it is accepted as a vehicle for “mutual enrichment.”’ [21]Alexander Schmemann, Letter to Protopresbyter George Grabbe, February 2, 1962, ROCOR Studies: Historical Studies of the Russian Church Abroad, … Continue reading

Orthodox Christians cannot equivocate between truth and falsehood– the methodology of the World Council of Churches, then, is unacceptable. Fr. Alexander believed that if participants in the ecumenical movement wish to bear witness to the Orthodox faith, then they must remain faithful to the understanding that Orthodox Christianity alone possesses the fullness of the truth. In other words, the truth of the Orthodox faith cannot be extricated from the fact that the Orthodox Church is the one true Church. [22] Schmemann, Church, World, Mission, 123. Later in the same letter, he elaborates on what that implies:

Our participation in the WWC becomes toxic at the exact moment when our conversation about faith changes into a discussion about so-called “ecclesiology.” For the Orthodox, the teaching about the Church depends directly upon the teaching of the Church, devoid from which it is senseless and meaningless. [23]Schmemann, Letter to Protopresbyter George Grabbe, February 2, 1962, ROCOR Studies: Historical Studies of the Russian Church Abroad, … Continue reading

The Orthodox hold that their Church is the only true “Church” in the mysteriological sense, but the World Council of Churches does not have a concrete definition of “Church.” As such, every Christian sect can be included. Fr. Alexander comments that this is a reflection of Protestant ecclesiology– perhaps he has the Anglican “branch theory” in mind. If Orthodox Christians accept the Protestant “denominational” principle, then they will neglect the Orthodox Church’s claim to be the true Church. They will, in fact, “[betray] … their own ecumenical mission and function.” [24] Schmemann, “Moment of Truth for Orthodoxy,” 55-56. A true witness to the Orthodox faith cannot be watered down by relativism.

Fr. Alexander was willing to speak out when he believed that a fellow Orthodox Christian had gone too far, but he also saw a danger in reacting too sharply against ecumenism. This is illustrated by his response to Metropolitan Philaret’s First “Sorrowful Epistle.” Fr. Alexander begins by acknowledging the legitimacy of Metropolitan Philaret’s concerns:

Most certainly it is the right and the duty of each bishop to communicate with his brothers on matters pertaining to the very essence of the Orthodox Faith, and who would deny that “ecumenism” in general, and more particularly the alarming trends made manifest at Uppsala, fall within this category? We can assure Metropolitan Philaret that he is not alone in having been “greatly shocked” by much of the Uppsala Report. [emphasis added] Many pronouncements and actions of Patriarch Athenagoras as well as Archbishop Iakovos, having provoked serious controversies among the Orthodox, are equally open to scrutiny by the Episcopate of the Church Universal. [25]Alexander Schmemann, “On the ‘Sorrowful Epistle of Metropolitan Philaret,” The Orthodox Church, vol. unknown (1969), Protopresbyter Alexander Schmemann, … Continue reading

Despite their differences, Metropolitan Philaret and Fr. Alexander agreed that contemporary trends in Orthodox ecumenism had become problematic. However, that is where their agreement begins and ends. Fr. Alexander does not address many of the other points in the Sorrowful Epistle, but rather turns his criticism to the activity of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia. His polemical tone is a sad product of the bitter relations between ROCOR and the Metropolia in the mid-twentieth century. Nonetheless, he makes some valid criticisms. He writes that Metropolitan Philaret is free to raise questions about ecumenism if he believes it is appropriate– after all, it is the responsibility of bishops to appeal to one another for the discussion of emerging doctrinal issues. However, Fr. Alexander argues that the final judgment on the issue can only be made by the decision of the Church as a whole. He argues that ROCOR has inappropriately usurped this prerogative, pointing in particular to ROCOR’s then-recent practice of receiving clergy from the Ecumenical Patriarchate without canonical releases. Fr. Alexander sees this as an implicit condemnation of the Ecumenical Patriarchate for heresy. If the actions of the Ecumenical Patriarchate truly amounted to heresy, then there must be “due process,” so to speak, before anyone can be condemned. In short, while Fr. Alexander recognized the dangers of more radical forms of ecumenism, he believed that these dangers needed to be addressed in a conciliar dialogue among Orthodox Christians before more drastic action like severing communion could be taken. In Fr. Alexander’s mind, however, differences of opinion with respect to ecumenism would not be an obstacle to Eucharistic Communion with other Orthodox. Although Fr. Alexander repeatedly expressed his own views on the ecumenical movement, it seems that he did not believe that his own opinion was the be-all, end-all for the Orthodox Church. He acknowledged the lack of an Orthodox consensus on ecumenism and the possibility for a diversity of views on the subject. However, he offers a stern warning against the dangers of a sectarian mindset, warning that the severing of communion can only lead to the “dead end” of schism. He concedes that there is plenty of room for discussion of the usefulness of ecumenical dialogue, and of how it should be conducted, but he concludes that to condemn all ecumenism as heresy is inappropriate. [26]Alexander Schmemann, “On the ‘Sorrowful Epistle of Metropolitan Philaret,” The Orthodox Church, vol. unknown (1969), Protopresbyter Alexander Schmemann, … Continue reading

Fr. Alexander’s frustrations on the question of ecclesiology were but one manifestation of the greater ecumenical problem presented by the great difference between the Orthodox and Protestant mindsets. Fr. Alexander recalls how at one ecumenical meeting in Hartford, Connecticut in 1975, despite the apparent warmness with which he was received by the Protestant participants, he could not escape a sense of “otherness” and alienation from them. This alienation was not the result of a simple doctrinal disagreement, but of a fundamental difference of mindset. [27] Schmemann, Church, World, Mission, 199. This is illustrated by Fr. Alexander’s comments on this meeting in his journals. Even though the other participants of the meeting hailed from various different Protestant groups, all of them communed together at a service before the meeting. Fr. Alexander found this puzzling; if they are already in communion, then “what other unity do they seek?” [28] Schmemann, Journals, 85-86. His bewilderment speaks to the great divergence between Eastern and Western Christian ecclesiological thought that has evolved over the past millennium, a divergence that Fr. Alexander himself cited as one of the chief difficulties in the ecumenical encounter between East and West. [29] Schmemann, “Moment of Truth for Orthodoxy,” 49-50.

Despite the desire for a genuine encounter with the Christian West, Fr. Alexander believed that Orthodox participation in the ecumenical movement was compromised by the difficulty of expressing Orthodoxy in a Western theological framework. [30] Alexander Schmemann, “Ecclesiological Notes,” St. Vladimir’s Theological Quarterly 11, no. 1 (1967), 35-39, https://www.schmemann.org/byhim/ecclesiological-notes.html accessed December 31, 2022. The ecumenical movement developed out of the Christian West, and discourse took place within a Western Christian frame of reference; the Orthodox, however, had been shut off from the Christian West for centuries. Consequently, the Orthodox were forced to work within a Western theological paradigm that was alien to the life of the Orthodox Church. [31] Schmemann, Church, World, Mission, 201-202. Fr. Alexander illustrates this problem by recounting his experience at the first assembly of the World Council of Churches in Amsterdam in 1948:

And I remember very vividly how, upon my arrival and while going through the registration routine, I met a high ecumenical dignitary who in a very friendly fashion, obviously with the intent to please me, informed me that the Orthodox delegates would be seated at the extreme right of the assembly hall together with the representatives of the Western “high churches” – such as the Swedish Lutherans, … the Old Catholics, and the Polish Nationals. From sheer curiosity– for certainly I had nothing against sitting with those excellent people– I asked him who made that decision? His answer was that it simply reflected the “ecclesiological” makeup of the conference, one of whose main themes would be precisely the dichotomy of the “horizontal” and “vertical” ideas of the Church. And obviously the Orthodox belong (don’t they?) to the “horizontal” type. To this I half jokingly remarked that in my studies of Orthodox theology I had never heard of such distinctions, and that without this information, had the choice been left to me, I might have selected a seat at the extreme “left” with the Quakers, whose emphasis on the Holy Spirit we Orthodox certainly share. [32] Schmemann, Church, World, Mission, 199-200.

Before the ecumenical conversation could even begin, the Orthodox had already been assigned a role within the ecumenical movement on the basis of Western theological presuppositions and categories. He continues:

We joined a movement, entered a debate, took part in a search whose basic terms of reference were already defined and taken for granted. Thus, even before we could realize it, we were caught in the essentially Western dichotomies– Catholic versus Protestant, horizontal versus vertical, authority versus freedom, hierarchical versus congregational– and were made into representatives and bearers of attitudes and positions which we hardly recognized as ours and which were deeply alien to our tradition. [33] Schmemann, Church, World, Mission, 200-201.

The Orthodox Church does not neatly fit into the ecclesiological categories of the West; if there is to be a real discussion, if there is to be a true witness to Orthodoxy, then the ecumenical movement must take a step back and reevaluate its fundamental frame of reference. Until this happens, however, he concludes that the Orthodox position within the ecumenical movement is “fundamentally false.” [34] Schmemann, “Moment of Truth for Orthodoxy,” 54. Shoehorned into a Western Christian paradigm, the Orthodox are unable to properly witness to their faith. Despite the ample representation of the Orthodox Church at the World Council of Churches, Fr. Alexander concludes that there is a very serious discrepancy between the discourse of “official” Orthodox delegates and the experience of “real” Orthodoxy. [35] Schmemann, “Moment of Truth for Orthodoxy,” 48, 54-55.

Fr. Alexander does, however, propose a potential solution for this problem. In his opinion, the ecumenical movement envisions the Protestant Reformation as the great, defining event of Christian history. For the Orthodox, however, the great divide that must be overcome is not the Catholic-Protestant divide, but the East-West divide. This division cannot be solved by relying solely on the Western Christian theological tradition. Rather, Fr. Alexander suggests that Orthodox Christians draw their basic frame of reference from the common Christian tradition of the first millennium: the Fathers, the Ecumenical Councils, and the liturgical tradition which still constitute the roots of the Western Christian tradition. He concludes,

Alien to the acute Western controversies and frustrations, the Orthodox Church could contribute, at least in her own eyes, a tertium datum, not as her tradition, but as a common heritage in which everyone can discover the starting point of his own spiritual and theological development. [36] Schmemann, “Moment of Truth for Orthodoxy,” 50-52.

He seems here to imply that the unique Orthodox contribution to the ecumenical movement could help Western Christians to overcome their own disagreements.

In conclusion, Fr. Alexander held a moderate position on the ecumenical movement, acknowledging the benefit of inter-Christian dialogue while maintaining a firm distinction between Orthodoxy and heterodoxy. He was initially optimistic about the potential of the ecumenical encounter, but he often found himself frustrated by the excesses of the World Council of Churches and by the statements of some of his fellow Orthodox. He recognized that the ecumenical movement presupposed a Protestant frame of reference, making it challenging to communicate Orthodox teaching. The assumption of a Protestant ecclesiology was particularly problematic because it placed all Christian groups on equal footing. A sense of relativism prevailed, neglecting the risk posed by genuine doctrinal errors. Fr. Alexander found this extremely problematic, and he frequently expressed his frustrations with the methodology of the ecumenical movement. He believed that this methodology failed to properly distinguish Orthodoxy and heresy, and Fr. Alexander was willing to speak out when he believed that fellow Orthodox Christians had fallen into this trap themselves. This is what he has in mind when he speaks of “bad ecumenism:” a blurring of the boundaries of the Church and a dangerous equivocation between truth and falsehood. Nevertheless, he did not consider disagreements about ecumenism to be an obstacle to Eucharistic communion with other Orthodox Christians. He believed that judgment on the matter should be decided in a conciliar manner by the whole Church. Despite all of the pitfalls of ecumenism, and despite his personal frustrations with the ecumenical movement, Fr. Alexander recognized the need to bear witness to the truth of the Orthodox faith whenever the opportunity presented itself. The ecumenical movement promised to be just such an opportunity. Fr. Alexander believed that interfaith dialogue gave Orthodox Christians a chance to share their faith with the heterodox and to make their Church more well-known and accepted in the West. He also saw the ecumenical movement as an opportunity to cooperate with other Christians and confront the rise of secularism in the West. This is what Fr. Alexander had in mind when he wrote of a “good ecumenism.” Interestingly, his perspective falls rather neatly in line with ROCOR’s own 2005 guidelines for interaction with the heterodox:

…the possibility of cooperation with the heterodox is not excluded, for example, in helping the unfortunate and by defending the innocent, in joint resistance to immorality, and in participating in charitable and educational projects. … In addition, dialog [sic] with the non-Orthodox remains necessary to witness Orthodoxy to them, to overcome prejudices and to disprove false opinions. Yet it is not proper to smooth over or obscure the actual differences between Orthodoxy and other confessions. [37]“On the Attitude of the Orthodox Church Towards the Heterodox and Towards Inter-Confessional Organizations,” 2005, ROCOR Studies: Historical Studies of the Russian Church Abroad, … Continue reading

One may reasonably question the usefulness of interaction with the heterodox, or wonder whether the potential benefits outweigh the risks. However, Fr. Alexander’s participation in the ecumenical movement and his reflections on the experience demonstrate that it is indeed possible to reap the benefits of “good ecumenism” without giving in to “bad ecumenism.”

Works Cited

Louth, Andrew, Modern Orthodox Thinkers: from the Philokalia to the Present. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2015.

“On the Attitude of the Orthodox Church Towards the Heterodox and Towards Inter-Confessional Organizations,” 2005, ROCOR Studies: Historical Studies of the Russian Church Abroad, https://www.rocorstudies.org/2022/12/13/on-the-attitude-of-the-orthodox-church-towards-the-heterodox-and-towards-inter-confessional-organizations/

Schmemann, Alexander, Church, World, Mission: Reflections on Orthodoxy in the West. Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1979.

Ibid., “Ecclesiological Notes.” St. Vladimir’s Theological Quarterly 11, no. 1 (1967), 35-39, https://www.schmemann.org/byhim/ecclesiological-notes.html

Ibid. and Schmemann, Juliana, trans., The Journals of Father Alexander Schmemann 1973-1983. Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2000.

Ibid., Letter to Protopresbyter George Grabbe, February 2, 1962, ROCOR Studies: Historical Studies of the Russian Church Abroad, https://www.rocorstudies.org/2015/12/12/protopresbyter-george-grabbe-correspondence-with-archpriests-georges-florovsky-and-alexander-schmemann/

Ibid., “Moment of Truth for Orthodoxy” in Unity in Mid-Career: an Ecumenical Critique, ed. Keith R. Bridston and Walter D. Wagoner. New York, NY: The Macmillan Company, 1963.

Ibid., “Notes on Evanston.” St. Vladimir’s Theological Quarterly 3, no. 1-2 (1954-1955), 58-60, Protopresbyter Alexander Schmemann, https://www.schmemann.org/byhim/evanston.html

Ibid., “On the ‘Sorrowful Epistle of Metropolitan Philaret.” The Orthodox Church, vol. unknown (1969), https://www.schmemann.org/byhim/sorrowfulepistle.html

Voznesensky, Metropolitan Philaret, “The First Sorrowful Epistle.” 27 July 1969, ROCOR Studies: Historical Studies of the Russian Church Abroad, https://www.rocorstudies.org/2021/01/24/a-first-sorrowful-epistle/

References

| ↵1 | Metropolitan Philaret (Voznesensky), “The First Sorrowful Epistle,” 27 July 1969, ROCOR Studies: Historical Studies of the Russian Church Abroad, https://www.rocorstudies.org/2021/01/24/a-first-sorrowful-epistle/, accessed December 31, 2022. |

|---|---|

| ↵2 | Alexander Schmemann, “On the ‘Sorrowful Epistle of Metropolitan Philaret,” The Orthodox Church, vol. unknown (1969), Protopresbyter Alexander Schmemann, https://www.schmemann.org/byhim/sorrowfulepistle.html accessed December 31, 2022. |

| ↵3 | Alexander Schmemann, Church, World, Mission: Reflections on Orthodoxy in the West (Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1979), 123. |

| ↵4 | Schmemann, Church, World, Mission, 207. |

| ↵5 | Alexander Schmemann, “Notes on Evanston,” St. Vladimir’s Theological Quarterly 3, no. 1-2 (1954-1955), 58-60, https://www.schmemann.org/byhim/evanston.html accessed December 31, 2022. |

| ↵6 | Schmemann, “Notes on Evanston,” St. Vladimir’s Theological Quarterly 3, no. 1-2 (1954-1955), 58-60, https://www.schmemann.org/byhim/evanston.html, accessed December 31, 2022. |

| ↵7 | Schmemann, Church, World, Mission, 199. |

| ↵8 | Andrew Louth, Modern Orthodox Thinkers: from the Philokalia to the Present (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2015), 195-196. |

| ↵9 | Alexander Schmemann, The Journals of Father Alexander Schmemann 1973-1983, trans. Juliana Schmemann (Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2000), 104, 109, 122, 133. |

| ↵10 | Schmemann, Journals, 322. |

| ↵11 | Schmemann, Church, World, Mission, 124. |

| ↵12 | Schmemann, Journals, 19. |

| ↵13 | Schmemann, Journals, 19-20. |

| ↵14 | Louth, Modern Orthodox Thinkers, 200-201. |

| ↵15 | Schmemann, Journals, 40, 111, 199. |

| ↵16 | Schmemann, Journals, 288. |

| ↵17 | Schmemann, Church, World, Mission, 203-205. |

| ↵18 | Schmemann, Journals, 125. |

| ↵19 | Schmemann, Journals, 122. |

| ↵20 | Alexander Schmemann, “Moment of Truth for Orthodoxy” in Unity in Mid-Career: an Ecumenical Critique, ed. Keith R. Bridston and Walter D. Wagoner (New York, NY: The Macmillan Company, 1963), 53-54. |

| ↵21 | Alexander Schmemann, Letter to Protopresbyter George Grabbe, February 2, 1962, ROCOR Studies: Historical Studies of the Russian Church Abroad, https://www.rocorstudies.org/2015/12/12/protopresbyter-george-grabbe-correspondence-with-archpriests-georges-florovsky-and-alexander-schmemann/ accessed December 31, 2022. |

| ↵22 | Schmemann, Church, World, Mission, 123. |

| ↵23 | Schmemann, Letter to Protopresbyter George Grabbe, February 2, 1962, ROCOR Studies: Historical Studies of the Russian Church Abroad, https://www.rocorstudies.org/2015/12/12/protopresbyter-george-grabbe-correspondence-with-archpriests-georges-florovsky-and-alexander-schmemann/ accessed December 31, 2022. |

| ↵24 | Schmemann, “Moment of Truth for Orthodoxy,” 55-56. |

| ↵25 | Alexander Schmemann, “On the ‘Sorrowful Epistle of Metropolitan Philaret,” The Orthodox Church, vol. unknown (1969), Protopresbyter Alexander Schmemann, https://www.schmemann.org/byhim/sorrowfulepistle.html accessed December 31, 2022. |

| ↵26 | Alexander Schmemann, “On the ‘Sorrowful Epistle of Metropolitan Philaret,” The Orthodox Church, vol. unknown (1969), Protopresbyter Alexander Schmemann, https://www.schmemann.org/byhim/sorrowfulepistle.html accessed December 31, 2022. |

| ↵27 | Schmemann, Church, World, Mission, 199. |

| ↵28 | Schmemann, Journals, 85-86. |

| ↵29 | Schmemann, “Moment of Truth for Orthodoxy,” 49-50. |

| ↵30 | Alexander Schmemann, “Ecclesiological Notes,” St. Vladimir’s Theological Quarterly 11, no. 1 (1967), 35-39, https://www.schmemann.org/byhim/ecclesiological-notes.html accessed December 31, 2022. |

| ↵31 | Schmemann, Church, World, Mission, 201-202. |

| ↵32 | Schmemann, Church, World, Mission, 199-200. |

| ↵33 | Schmemann, Church, World, Mission, 200-201. |

| ↵34 | Schmemann, “Moment of Truth for Orthodoxy,” 54. |

| ↵35 | Schmemann, “Moment of Truth for Orthodoxy,” 48, 54-55. |

| ↵36 | Schmemann, “Moment of Truth for Orthodoxy,” 50-52. |

| ↵37 | “On the Attitude of the Orthodox Church Towards the Heterodox and Towards Inter-Confessional Organizations,” 2005, ROCOR Studies: Historical Studies of the Russian Church Abroad, https://www.rocorstudies.org/2022/12/13/on-the-attitude-of-the-orthodox-church-towards-the-heterodox-and-towards-inter-confessional-organizations/ accessed January 5, 2023. |

Great article, thanks for posting it. I know that Fr Alexander Schmemann has a controversial reputation in some Orthodox circles, but I have always loved and have been deeply touched by his writings. Probably because, like him, I’ve also often felt like I lived between two worlds — an Orthodox Christian mindset and way of viewing the world that I knew as a child and that was considered normative at home, vs then going to Western/secular schools and living in the Western/secular world, where the prevailing worldview is completely different.

Fr Alexander is spot on: for the Western Christian, Christian history pretty much begins at the Protestant Reformation. It’s as if nothing important happened before then. It’s a cultural bias which Westerners are often completely unaware of, because it’s the Western cultural sea that they/we swim in. In my very good public high school in PA, I had a wonderful world history teacher, but we devoted about one paragraph to the Byzantine Empire and pretty much nothing about pre-communist Orthodox history in Eastern Europe……

For Orthodox Christians living in the West, seems that being aware of the cultural presuppositions as far as how “Christianity” and the Christian life are defined is of paramount importance. We see the implications of this today, where our Orthodox Christian approach to the Lenten period is far, far different than that of many Western Christians…. same during Advent in our approach to the Nativity.

Thanks for all of your work here on these pages. I love reading so many of these articles. Thanks be to God for all of these luminaries outlined on these pages who laid the foundations for Orthodox Christian life in the West… those who helped “show us the way” and whose lives still teach us discernment as we navigate living in two worlds.

An amazing article, thank you. I’d encountered Fr Schmemann some years ago whilst studying sacrament, though only attended Divine Liturgy for the first time this past sunday. Even that first encounter with orthodoxy has made many point in you article fit into place.

My favourite was the 1948 WCC anecdote, in particular, Fr Alexander’s comment on vertical and horizontal theology were not distinctions in Orthodoxy, and he might have easily been place with Quakers for there emphasis on the Holy Spirit.